Terence P. Dolan’s Dictionary of Hiberno-English is not like any other dictionary or, for that matter, like any other reference volume. It’s the first general dictionary of the Irish dialect of English ever published and, in spite of its heady title, a good read for Irish and Irish-American word-hoarders and word-mongers — from the burly longshoremen on Pier 54 to the bifocaled tweedy set at the Fifth Avenue Library.

The Irish have always had a fascination for words. Anthony Burgess, the Englishman who invented his own language in A Clock-work Orange, and who wrote critically about James Joyce, once complained, “It’s too easy for Irish writers to be poetic.” Dolan’s Dictionary of Herberno-English is a journey through Irish-English that not only explains the Irish popular fascination for “the word” and Burgess’s notion of “genetic genius,” it captures the uniqueness of the English language as it’s spoken and written in Ireland.

The compiler-editor, a leading authority on Hiberno-English and Professor of Old Middle English at University College Dublin, makes no case for the linguistic superiority of either English or Irish, but as a broguish linguist, he clearly subscribes to the same description of Gaelic as Old Hugh, Brian Friel’s hedge schoolmaster in Translations – “Yes, it is a rich language…full of the mythologies of fantasy and hope and self-deception – a syntax opulent with tomorrows.” And Dolan uses Irish-language proverbs and literary references in profusion — from Swift, Carleton, Yeats, Joyce, Heaney, Doyle, Binchy, McCourt and others — to illustrate the richness and opulence of that Hiberno-English.

The compiler-editor, a leading authority on Hiberno-English and Professor of Old Middle English at University College Dublin, makes no case for the linguistic superiority of either English or Irish, but as a broguish linguist, he clearly subscribes to the same description of Gaelic as Old Hugh, Brian Friel’s hedge schoolmaster in Translations – “Yes, it is a rich language…full of the mythologies of fantasy and hope and self-deception – a syntax opulent with tomorrows.” And Dolan uses Irish-language proverbs and literary references in profusion — from Swift, Carleton, Yeats, Joyce, Heaney, Doyle, Binchy, McCourt and others — to illustrate the richness and opulence of that Hiberno-English.

For Dolan, every word not only has a history, it is itself a history. On a single page (251), see how he treats entries that are so different and yet so Irish, entries like “soft” and “so long”:

soft /soft/:misty and rainy (usage influenced by Ir bog, soft and wet): overgenerous, lenient, gullible; slightly retarded or `simple’ (GF, Galway). `It’s a fine soft morning’; `Soft day!’ (a common greeting). Joyce, Finnegans Wake, 619.20: “Soft morning, city!” and so long/’s…s/: It has been claimed that the American farewell `so long’ may be derived from Ir slán…instead of Goodbye, they thought they were hearing So long), but the connection is improbable — as are the suggestions that it may originate with Hebrew sholom or Arabic salam, peace.

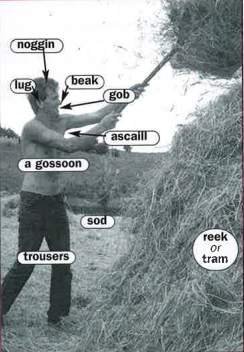

Look, too, at other entries that echo the past – special words with special meanings, like “phoney,” “craic,” “delf,” “gripe,” “peg,” and “slob.” Imbedded in these words and their stories are bits of the Irish personality, which are, of course, bits of the Irish-American personality as well. Readers who would better understand why it is they can’t answer “no” and why their parents and grandparents couldn’t answer “no,” need only consult Dolan’s entry for “no” on page 185. Simply put, in the Irish language, there’s no way to answer a question with a “no,” and the structure eased into the English. That’s it!

From Tom Paulin’s insightful foreword to Dolan’s useful bibliography, this volume informs. Paulin touts the book as “a national dictionary,” a gathering of “innumerable local words from all parts of Ireland together – a hospitable, inclusive text…without triumphalism.” Certainly it catalogues the poetic speech of the Irish people and sets a linguistic landscape for the study of Irish-English.

Dolan’s introduction to the dictionary offers a short but incisive essay on the etymologies, grammar and history of the English language as spoken in Ireland, as well as the editor’s comments on the distinctive evolution of the dialect. He notes, for example, that “whiskey” is, at root, “the water of life,” and he provides that touch of the folk-sage in his illustration: “What butter or whiskey’ll not cure, there’s no cure for.”

And he’s “mad” to explain why the Irish have their own ways of saying, “I’m after eating my dinner,” or “I wonder what age is she?”

Dolan makes clear that Hiberno-Irish has its own word stock, its own structures, its own history. The comprehensive bibliography that completes the volume leads the reader to the sources beyond the text.

The Dictionary of Hiberno-English will not only help Irish-Americans better understand their grannies, it will explain to them their own idiosyncratic use of language and strange turns of phrase. The bottom line is that this dictionary is an essential source book for the serious linguistic or literary scholar, as well as a good read for the linguistically curious.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January 2000 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply