“On June 25 I was awakened at daybreak by my lover’s tapping at my door and calling to me: ‘Get up, get up, it is time to be married!'”

Thus the Englishwoman whose love affair changed the course of Irish history was to recall the fateful morning when she married her man of destiny, not beneath the high eaves of a great cathedral but in a humble side-street registry office in the market town of Styening in West Sussex.

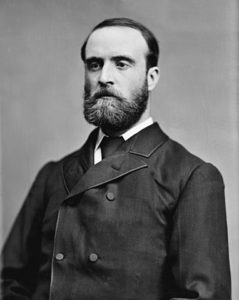

In 1936, one of the most highly publicized romances of our time, an American divorcee, Mrs. Wallis Warfield Simpson, prompted the uncrowned king of England, Edward VIII, to give up the throne because of his love for her; less than half a century before, however, Charles Stewart Parnell, “the Uncrowned King of Ireland,” sacrificed his political career and spun irrevocably the helm that altered the course of Irish history, because of his love for Kitty O’Shea.

They met on a day of destiny in 1880 in the Palace Yard at Westminster. He was a Protestant landlord from County Wicklow who made an unlikely entry into politics as a nationalist, becoming leader of the Home Rule Party. She was Katharine O’Shea, nee Ward, a daughter, of Queen Caroline’s chaplain, granddaughter of a lord mayor of London, sister of a field marshal. She was also the uneasy wife of Captain William Henry O’Shea, a member of Parnell’s own party, who had received part of his education at Dublin’s Trinity College. At the time of her first meeting with Parnell, Kitty O’Shea’s marriage was already in troubled waters, her husband spending much of his time abroad, attending to business interests in Spain. In fact, since 1875, the couple had virtually lived apart.

Kitty was to remember that first meeting in Palace Yard: “In leaning forward to say goodbye a rose I was wearing in my bodice fell out on my skirt. He picked it up and, touching it lightly with his lips, placed it in his buttonhole. This rose I found long years afterward done up in an envelope, with my name and the date, among his most private papers, and when he died I laid it upon his heart.”

A second meeting shortly afterwards confirmed their mutual infatuation and within a matter of months Parnell was writing to her as “My dearest love…”

Soon, all pretense was dropped and Parnell, when he was attending parliament in London, stayed with Kitty at her home, Wonersh Lodge, North Park, Eltham, Kent.

That Captain O’Shea was fully aware of what was going on from an early stage is certain. However, for years he made no move, perhaps thinking that the illicit liaison between his party chief and his wife might prove politically advantageous to him, and, anyway, he had long since lost interest in Kitty.

Yet, eventually, the casual meeting in Palace Yard was to lead to what was to be called “the most notorious divorce case of the 19th century.”

Although once, when asked why he did not get married, Parnell had replied: “I am married to my country,” he nevertheless enjoyed a full relationship with Mrs. O’Shea.

There were frequent trips home alone to Ireland, to his lovely ancestral home, Avondale, where he planned someday to settle down with Kitty. Sadly, this hope was not realized; Kitty O’Shea was never to see Avondale and, in fact, she was never to see Ireland.

In England, however, he and Kitty enjoyed a full domestic life together. She fought a constant battle to get him to pay more attention to his personal appearance and to give more thought to the clothes he wore. One parliamentary commentator said, with some justifications, that Parnell looked like “a cross between Mr. Oscar Wilde and a scarecrow.”

Nor did their affair ever lose its first idealistic flush of romance. Parnell loved roses, especially white roses, so Kitty sent to Wrocester to procure a special breed of white rose, which she was able to keep in bloom all year round in her conservatory at Wonersh Lodge. Thus, she could always supply him with a buttonhole whenever he had to make a speech in the House of Commons or on some other important occasion.

During these years of bliss, Kitty was to bear three children for the Irish leader.

However, what had long been a smoldering threat to Parnell and Kitty on a personal level now emerged as a menace to the slow process of Home Rule for Ireland being so carefully nurtured by Parnell and the British Prime Minister, Gladstone.

All pretense was cast aside, and all reticence shattered, however, when, in 1890, William Henry O’Shea sued Kitty for divorce, citing Parnell as co-respondent.

Almost overnight the dream of Home Rule was splintered as the party split, some members forsaking their leader, others remaining faithful to the man—divorce or no divorce—whom they still considered their “uncrowned king.” Parnell’s career was wrecked; in nine months he would be dead.

When summer came, they married. The ceremony took place in the Registry Office in Styening on Thursday, June 25, 1891.

“My King looked at us both in the small mirror on the wall of the little room and, adjusting his white rose in his frock coat, said joyously: ‘It is not every woman who makes so good a marriage as you are making, Queenie, is it? And to such a handsome fellow, too!’ blowing kisses to me in the glass.”

Parnell said to her that day: “The storms and thundering will never hurt us now, Queenie, my wife, for there is nothing in the wide world that can be greater than our love.”

Over the following months, although he tried to keep active, Parnell was obviously an ailing man. When he died at Kitty’s home, No. 10 Walsingham Terrace, Brighton, shortly before midnight on October 6, 1891, the unexpected news sent shock waves across England and Ireland.

A shattered Gladstone said later, striking the arm of his chair with his hand: “Poor fellow! Poor fellow! I do believe firmly that if these divorce proceedings had not taken place there would be a Parliament in Ireland today.”

Kitty, years later, recalled vividly the closing moments of her lover’s life: “Late in the evening he suddenly opened his eyes and said: ‘Kiss me, sweet Wifie, and I will try to sleep a little.’ I lay down by his side and kissed the burning lips he pressed to mine for the last time.”

Kitty O’Shea. was to outlive Charles Stewart Parnell by thirty years. She died in the early morning of February 5, 1921, in a small terraced house she rented on a side road in Littlehampton.

She is buried in the municipal cemetery in that little Sussex town: Parnell rests under a rough-hewn granite memorial in Dublin’s Glasnevin.

This article by John J. Dunne originally appeared in the April 1991 issue of Irish America magazine.

I’ve been to Avondale and I found this article very informative. A similar one about William Henry O’Shea would also be interesting. Perhaps Irish America will get around to doing one some day.

Sincerely, Harry Dunleavy