Tracing the origins of Memorial Day can become rather convoluted. After all, about two-dozen U.S. communities claim to have held the first such commemoration. On a less contested level, Gen. John A. Logan was the man who established an official day to honor military persons who made the ultimate sacrifice.

Born on Feb. 9, 1826, in Jackson County, Illinois, he was one of ten children belonging to Elizabeth Logan née Jenkins, and Dr. John Logan, a native of County Monaghan. The younger Logan spent much of his adolescence playing the fiddle and racing thoroughbred horses. In his early 20s, he served in the Mexican-American War. Though he did not see any combat, he almost succumbed to a case of measles, as related by the website of the General John A. Logan Museum.

Returning to Illinois, Logan obtained a court clerkship in his native Jackson County. He also studied law at the University of Louisville (Kentucky). Not long after graduation, he became a prosecuting attorney in the Illinois Third Judicial District.

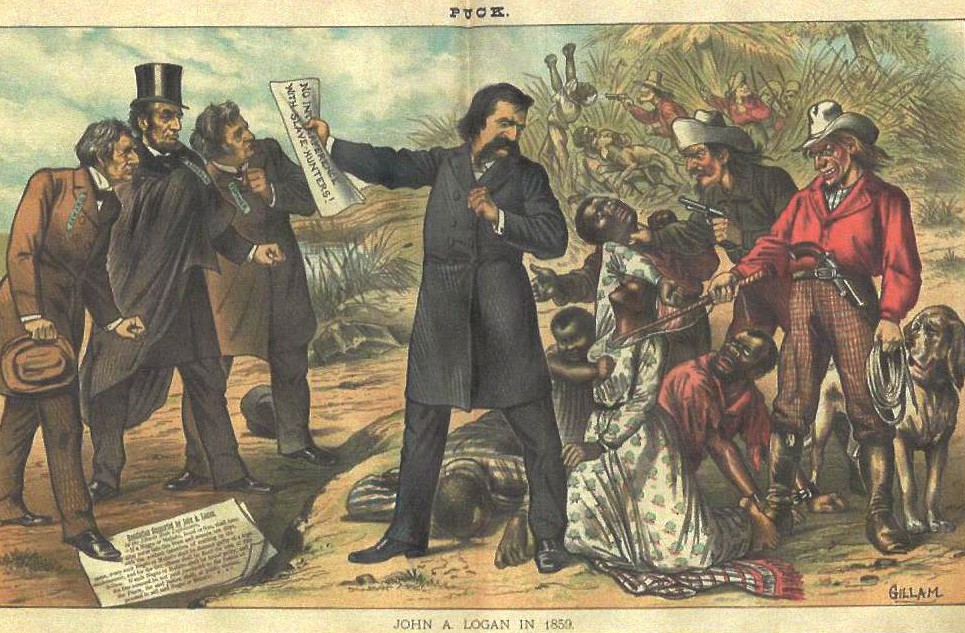

Additionally, he obtained a seat in the Illinois House of Representatives, where he used his power in an objectionable fashion, spearheading a bill to prohibit any and all African-Americans from entering the state. Though Illinois was technically a northern state that would fight alongside the Union, a large proportion of its residents supported slavery. This position was particularly popular in the southern part of the state, which was Logan’s native region.

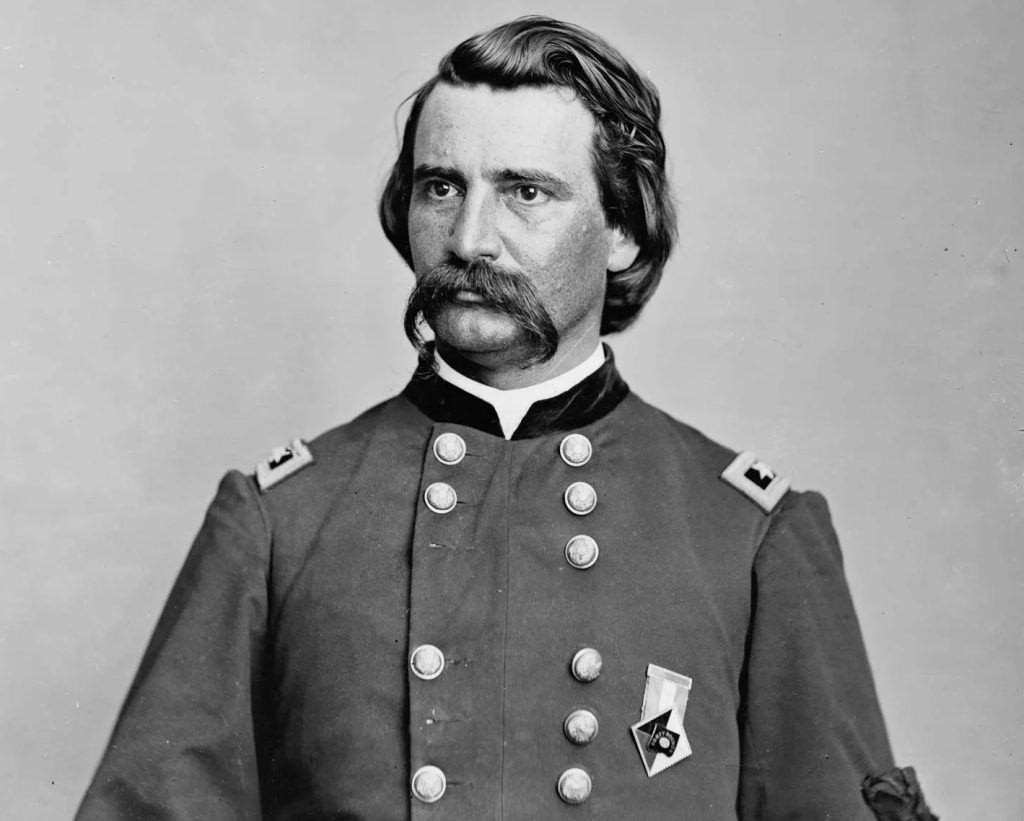

In the antebellum period, Logan had scant use for abolitionists, and he was displeased when Abraham Lincoln became President. But with the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War, he began to find the right side of history. First fighting as a volunteer, he later officially entered the Union Army as a colonel in the 31st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Not long into his action-packed Civil War tenure, he was showing a change of heart regarding his position towards African-Americans, describing slavery as a “cursed institution” that should be “thoroughly wiped out.” In this epic struggle for freedom, Logan – who was wounded in the February 1862 Battle of Fort Donelson – earned the reputation as a brave, decisive officer and attained the rank of major general.

Following the Civil War, Logan served two terms as a U.S. Congressman and three terms as a U.S. Senator. He was a politician who had “awoken,” as people might say nowadays. He actively supported causes that benefited both African-Americans and women.

Additionally, he served as commander of the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal organization of Union military veterans. In this role, he designated May 30 “for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land.”

The website usmemorialday.org mentions that on the first official day of commemoration (May 30, 1868), some 5,000 persons decorated the graves of 20,000 soldiers, both Union and Confederate, at Arlington National Cemetery.

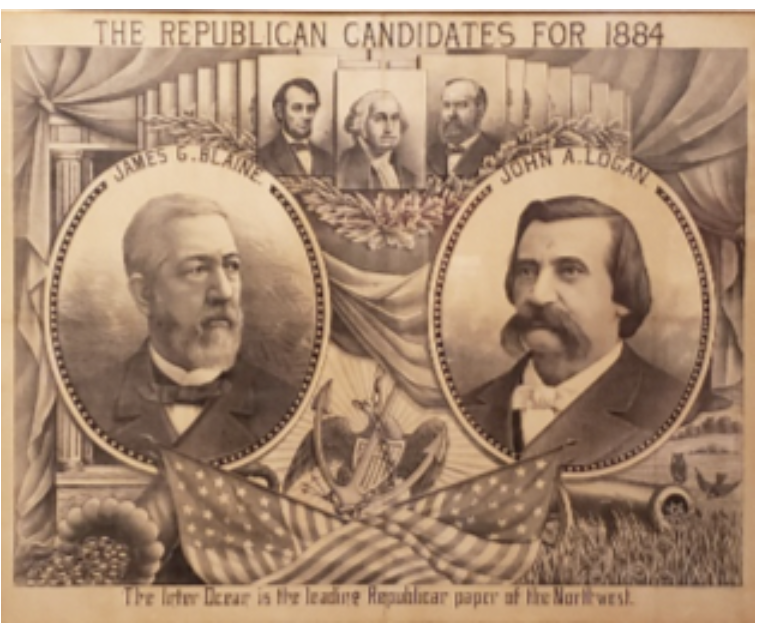

Memorial-Day-OrderThis day of remembrance would continue to grow. So would Logan’s political prospects: In the 1884 presidential campaign, he was the Republican Party’s nominee for Vice President. During this campaign, he had received a resounding endorsement from none other than Frederick Douglass, who said of Logan, “If there is any statesman on this continent, now in public life, to whose courage, justice and fidelity, I would more fully and unreservedly trust the cause of the colored people of this country or the cause of any other people, I do not know him.”

Logan was the Republican Vice-presidential candidate in 1884 and was looking forward to being that party’s Presidential candidate in 1888.

Outside of the political domain, Logan had three children (two of whom survived childhood) with his wife Mary Logan née Simmerson Cunningham. She was a prominent nonfiction writer who authored such books as How Memorial Day came to be. Logan himself authored two books on the Civil War, The Great Conspiracy: Its Origin and History and The Volunteer Soldier of America.

Following a period of inflammation and swelling in his limbs, he died at age 60 on Dec. 26, 1886. Historian Gary Ecelbarger, the author of the biography Black Jack Logan: An Extraordinary Life in Peace and War, says that, at the time of Logan’s death, many Americans considered him the front-runner to become President in the upcoming 1888 election.

Logan’s son, Maj. John A. Logan, Jr., died at age 34 in the 1899 Battle of San Jacinto, part of the oft-neglected Philippine–American War. He is one of the more than 1.2 million veterans whom Memorial Day seeks to recognize.

Owing to the custom of honoring soldiers by decorating their graves, the day was originally known as Decoration Day. In 1873, New York became the first state to formally recognize it. By 1890, all northern states had followed suit. At this point, people were often referring to the day as Memorial Day.

The southern states were rather more resistant to extending official recognition, but that started to change in the wake of World War I, when the country decided that Memorial Day would commemorate not only Civil War veterans but those who died in all U.S. wars.

The website of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs tells how the likely motivation for holding commemorations at the end of May was that flowers would be blooming nationwide. For one full century, May 30 endured as the date of observation. But since the National Holiday Act of 1971, Memorial Day has taken place on the final Monday of May.

For all his prominence during the latter decades of his life, the name of John A. Logan faded during the 20th century. That said, the considerable number of statues, schools, and communities bearing his name gives an indication of his former notoriety. And his contribution to fallen soldiers will endure for as long as memory and honor remain.♦

Ray Cavanaugh is a freelance scribe from Massachusetts. His mother is from Kerry and his father is a few generations removed from Wexford. He’s a regular “Window on the Past” contributor to Irish America.

Great story, except for the fact the “African-Americans” did not exist in the 19yh century.

A very interesting story and great research.