By Abdon Moriarty Pallasch

St. Brendan the Navigator, early transatlantic voyager, died on May 16, 587. Tim Severin (d. 2020) who retraced the 6th century legendary journey of St. Brendan from Ireland to Newfoundland and talked the adventure with Abdon Pallasch.

The idea that Irish monks in an ox-hide boat might have beaten the Conquistadors and the Vikings to America was largely relegated to Irish folklore before 1976.

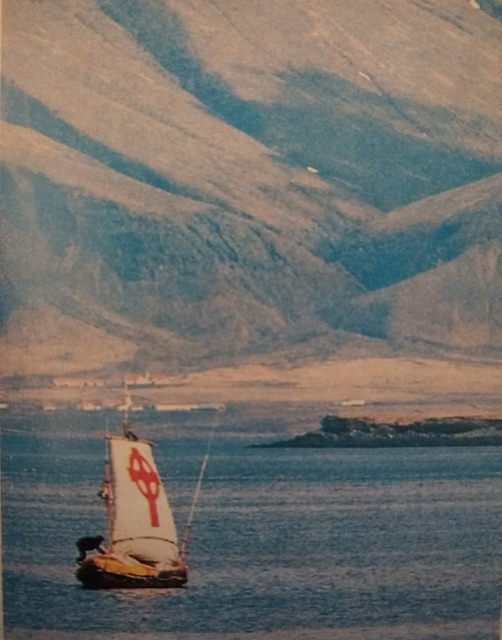

That year, British navigation scholar Tim Severin set off from Ireland in an ox-hide leather “currach” to prove that St. Brendan the Navigator and his followers could indeed have sailed to American and back again in the 6th century.

His landfall on Newfoundland after four months sailing proved Brendan’s voyage could be done with medieval material and medieval technology,” said Severin, who now lives in Courtmacherry, Cork.

Severin first learned of St. Brendan’s voyage while studying navigation at Harvard in the 1970’s when he happened on Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abatis (Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbot), a Latin text dating from the 9th century, copies of which have survived in monasteries around Europe. (“A medieval best-seller,” Smithsonian magazine called it.)

It was the Navigatio’s detailed description of Brendan’s boat which piqued Severin’s interest. Brendan’s monks tanned ox-hides with oak bark, stretched them across the wooden frame of a boat, sewed them with leather thread, and smeared them with fat to seal them against water – a composition that would preserve a boat well in cold water, Severin thought.

Opening a nautical map of the North Atlantic, Severin said he was amazed by the obviousness of the route Brendan would have had to take to reach America.

The only westward-flowing current available to ships sailing from Ireland would be the northernmost part of the Atlantic, hugging the coasts of Iceland and Greenland – the route Leif Ericson, the Viking, would follow in the 10th century.

“It was like all the pieces of the puzzle suddenly fell in together,” he said.

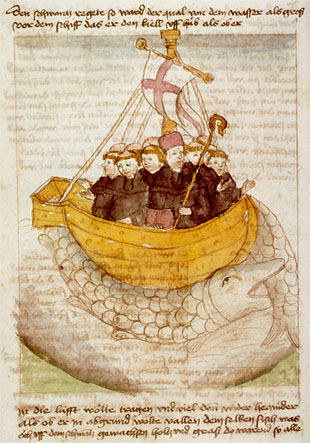

“Monks seeing icebergs for the first time would call them crystals. “Volcanic activity off the coast of Iceland would spew red-hot sulfur-smelling rocks into the ocean,” as mentioned in the Navigatio.

With help from other enthusiasts of the Brendan legend in both Ireland and England, Severin literally sewed together an old-fashioned replica of Brendan’s currach using materials that would have been present in Brendan’s day.

In May, 1976, Severin and his crew set off from Brandon Creek, in that remote area of Kerry’s Dingle Peninsula where fishermen still build currachs for themselves.

The leather sails of the St. Brendan carried them north to Scotland where Brendan had visited other priests; then northwest to the Danish Faroe Islands, where another “Brandon Creek” still marks the spot where natives believe Brendan disembarked. Severin’s crew waited out the winter in Iceland.

Many of the stops on Brendan’s legendary voyage were at islands where Irish monks had set up primitive monasteries. Norsemen who later sailed these waters and landed on these islands would record the presence of Irish priests who they called “Papers” (Fathers).

Severin said he was surprised at the friendliness of whales that swam around the boat and even underneath it. The few ships that travel those icy northern waters are usually freighters with large engines. By contrast, Severin’s boat “looked more like a whale – skin stretched over a bony frame – and far less menacing,” he said.

Fourteen hundred years ago, before whales had any contact with man, Severin feels they may have felt uninhibited enough to surface with a boat on their back, as told in the Navigatio, certainly, some of the whales could have been viewed as “sea monsters,” he said.

Severin’s boat survived a puncture by the columns of floating ice off Canada. While a puncture might have sunk a fiberglass boat, Severin and his men were able to sew a new piece of ox-hide over the hole.

While Severin’s crew had a few modern conveniences such as a radio and dried meats, he had to endure the same cold and wetness Brendan’s monks endured. He also tasted their diet of fish and sea birds.

“For hardy 6th-century monks used to living off fish and birds in stone cliffs on barren rocky islands, a sailboat ride to America wouldn’t have seemed as daunting,” Severin said.

Severin’s crew landed in Newfoundland, Canada, on June 26, 1977, in the area where they believed Brendan and his men would have landed.

While Severin’s journey does not prove that St. Brendan did make the voyage to North America, it does prove that a small leather boat or currach of the type that is described in Navigatio could make the journey by the route laid down by the Latin text. What is also obvious is that the Irish were pioneering seafarers of the North Atlantic currents almost 1,000 years before Columbus set foot in America.

The Brendan legend was better known around Europe during Columbus’ time than Leif Ericson’s because of the Catholic Church’s network of monasteries. “Columbus was aware of the legend of St. Brendan,” said William McKee, a history professor at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida. “It was an important part of the folklore and legend in medieval Europe. It may have influenced Columbus to sail west, looking for Brendan’s ‘Promised Land of the Saints’ while he sought a passage to India,” McKee said.

Maps from Columbus’ day often featured an island or islands in the western Atlantic called, “St. Brendan’s Isle.”

“It may well be that navigators from Ireland came across the Atlantic and touched ground at Newfoundland said Michel Gannon, a history professor at the University of Florida. “I would like to think that because I’m Irish myself.”

More conclusive proof may come from a site in West Virginia where stone carvings dating to some time between the years 500-1000 have been discovered. Analysis by archaeologist Dr. Robert Pule and a leading ancient language expert, Dr. Barry Fell, indicate that they are written in Old Irish employing the Ogham alphabet. According to Dr. Fell, the “West Virginia Ogham texts are the oldest Ogham inscriptions recorded from anywhere in the world. They exhibit the grammar and vocabulary of Old Irish in a manner previously unknown in such early rock-cut inscriptions in any Celtic language.” Dr. Fell goes on to speculate that, “It seems possible that the scribes who cut the West Virginia inscriptions my have been Irish missionaries in the wake of Brendan’s voyage, for these inscriptions are Christian because the early Christian symbols of piety, such as the various Chi-Rho monograms (Name of Christ) and the Dextera Dei (Right Hand of God) appear at the sites together with the Ogham texts.”

The legend of St. Brendan is powerful enough that Irish Americans from New York to San Francisco and from Boston to Daytona Beach, have chosen St. Brendan as the namesake for their parishes.

In 1978, Clearwater Beach Catholics, many of them Irish-Americans, built a church on Island Estates, where just about every family has a boat docked out back. They saw a symmetry between Brendan and his men setting off in an ox-hide currach from Kerry’s Brandon Creek and a church named for him on an inlet of Florida’s Intracoastal Waterway next to a marina that specializes in modern fiber-glass boats.

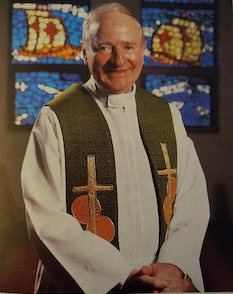

“It’s a maritime area,” said Cavan-born Father Edward Mulligan.

The church’s 14 stained glass windows depict St. Brendan’s seven-year odyssey as recorded in the Navigatio: sailing past the crystal that stretched up to the clouds; past the “Island of [black]smiths” where inhabitants hurled flaming, foul-smelling rocks at the monks, and finally, landfall in the sweet-smelling “Promised Land of the Saints.”

Brendan and his monks explored until they came to a “great river” that divided the land. Then they sailed back to Ireland.

“The Irish are lousy historians,” said Monsignor James McMahon, pastor of St. Brendan’s parish in Brooklyn. McMahon went to Ireland and looked for documents or authenticated histories of Brendan’s life and was disappointed to find little.

McMahon, a former history teacher and a self-professed skeptic when it comes to historical legends, nonetheless believes the Brendan story must be based on an actual great voyage of some sort.

when he served as pastor of St. Brendan’s Parish in Clearwater, Florida.

Fr. Edward Mulligan is willing to take it on faith.

Historians believe Brendan was born about 484 A.D. near Tralee in Kerry. He was ordained by Bishop Erc and sailed far and wide spreading the faith and founding monasteries, the largest at Clonfert, Galway, where he was buried in 577 at the age of 93. But when Mulligan was studying in the seminary in Dublin, the priests didn’t dwell too long on St. Brendan’s accomplishments.

“He was kind of overshadowed by St. Patrick,” Mulligan said.

But when Mulligan, like Brendan before him, left his home and family to travel to America as a missionary, he took a new interest in the Brendan legend.

“When I came to this country, I began to study everything I could get a hold of regarding St. Brendan,” he said.

Mulligan had become a firm believer in the story, and he carried on the faith like other Irish immigrants and Irish-Americans.

“There’s so much evidence that it really was possible to make the journey,” Mulligan said.♦

This article was first published in Irish America in July/August 1992.

NOTE: In 2016, Tim Severin celebrated the 40th anniversary of his epic journey. He passed away on December 18, 2020 (aged 80) in Timoleague, West Cork.

ABOUT THE WRITER: Abdon Moriarty Pallasch was a reporter for the Chicago Sun-Times, the Chicago Tribune and The Tampa Tribune. He is now Director of Communications for Illinois Comptroller Susana Mendoza. His grandparents, Tim & Kate Moriarty, emigrated to Chicago from Kerry.

Since Columbus is now thought of in very negative terms in parts of the US, I have been telling everyone who will listen that we should celebrate the discovery of North America by St. Brendan on his feast day May 16.

Legend and folklore. While the trip in itself is interesting, even fascinating, it took centuries to be told and there was no contribution to mankind as a result of St. Brendan’s trip. Christopher Columbus opened the world to us all.

and the Chinese were here before them!

Great story! I have heard of the voyage since I was youn and remember Tim Severin setting sail in his curragh.

Can you prove it?

Excellent story. Since I’ve been a ship’s officer and have been to 82 countries, I found it very interesting.

Severin wrote a book about his voyage, “The Brendan Voyage”. Fascinating read!

I have heard of St. Brendan from I was very young, I am now 90, my teacher in Ireland mentioned him often, and the fact that St. Brendan reached America long before Lief Erickson. I also remember Tim Severin starting out on his voyage. I think I wrote this before?