The most trusted designated driver of all time has died. Astronaut Michael Collins passed away at his home in Florida on April 28. He was 90 years old, and he had been battling cancer.

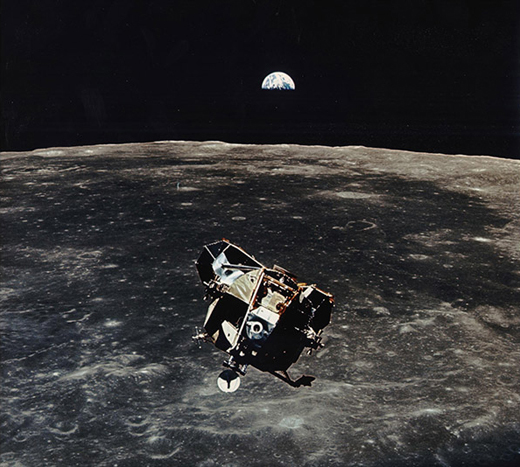

On July 20, 1969, two American astronauts landed on the moon and became the first humans to walk on the lunar surface. As the astronaut in charge of orbiting the Moon as his crewmates, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, collected samples and photographs, Michael Collins spent nearly 24 hours alone in space – at times going hours without radio connection.

The most crucial part of the mission was ensuring Aldrin and Armstrong connected back to the main spacecraft. When describing the steps that had to be taken in order to correctly execute the reunion of two vehicles in space, Collins wrote in his book, Carrying The Fire: An Astronaut’s Journey, “Against all instinct, one must apply thrust away from the direction of the target, drop down into a lower, faster orbit, and then transfer back up into the original orbit at precisely the right point in the catchup trajectory…”

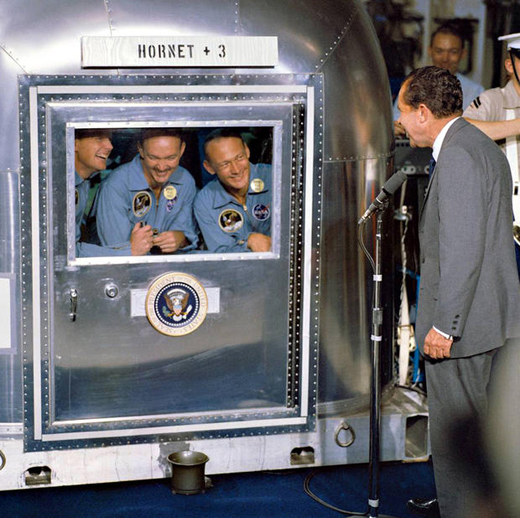

After successfully picking up the lunar explorers, complete with 48 pounds of moon rock and soil samples, the trio was on its way back to the familiar blue oceans, brown land, and white clouds of Mother Earth, splashing down on July 24, 1969 in the Pacific Ocean.

The son of a U.S. army officer, Collins was born in Rome on October 31, 1930 and groomed to serve his country. His father, Major General James Lawton Collins, had served in World War I and World War II, and was acting as Defense Attaché to Italy when the future astronaut was born.

James, himself, had been born into a large Irish American family in Algiers, Louisiana, in 1882. His father, Jeremiah Bernard Collins, had left Dunmanway, County Cork as a young boy in the early 1860s to join the rest of the family in Cincinnati, Ohio. Family lore has it that at 16, Jeremiah served as a drummer boy in the Civil War.

Jeremiah made his way to New Orleans after the war, worked for a grocer, James Lawton, and eventually married Lawton’s daughter, Kate. Together they established a successful dry good store with a pub in the back, and had 11 children. Their first son, James Lawton Collins, named for Kate’s father, graduated from West Point and went on to a distinguished career in the military.

Like his father, Michael Collins also sought a military career. After graduating from West Point in 1952, he joined the air force and while accumulating flying hours at Edwards Air Base in California, he learned that NASA was searching for a new crew of astronauts. Collins started at NASA in 1963; after six years at the job, months of careful planning, and 400 hours in command-module simulation, Command Module Pilot Collins launched an eight-day mission that over half a billion pairs of eyes watched on television screens across the globe.

The flight to the moon, began as a challenge to NASA by the American president. It was at the start of the term at Rice University in Houston, Texas, 1962, that then-President John F. Kennedy declared the United States would touch down on the Moon by the end of the decade. NASA was four years old, Michael Collins and Patricia Mary Finnegan Collins had just celebrated their five-year wedding anniversary, and America had just celebrated her 186th birthday. The task was daunting, but the curiosity and excitement for space exploration had been bursting in Collins’ blood since he’d read the Buck Rogers comic strips.

Interviewed July 14 on CBS Sunday Morning by Jeffrey Kluger, Collins said, “I hark back almost daily to John F. Kennedy. I felt that we were fulfilling, if successful, his mandate. And I was just thrilled to be a piece of the whole thing.”

Kluger asked Collins, “Do you at all regret not having closed that final 60 miles, and left Collins boot prints on the Moon?”

“No,” he replied. “I’d be a liar or a fool if I said I had the best seat on Apollo 11. But I felt that I was an important part of it. When I was behind the Moon I later discovered I was being described as, oh, lonely, lonely, lonely. I was happy back there. I had my own little domain. And actually, going down and touching the Moon, eh, that was not high on my list.”

Astronaut Eileen Collins the first woman to command a space shuttle, talked about Collins’ feat in an 1999 interview with Irish America (available online) and in a more recent email to the magazine she said: “Michael Collins had an extremely difficult job. He knew he would not have the opportunity to actually walk on the Moon, yet he supported the mission from lunar orbit. He was very focused on maintaining that the Apollo service module was in great shape, while orbiting the Moon, so it was ready to take the crew back home. He also had to be ready to react in an emergency. This took a very humble person. Also, obviously, his intelligence and discipline made the mission a great success. I recommend people read his book, Carrying The Fire, written in 1974. It is one of the best books written on the Apollo moon program! I read it while I was an Air Force pilot, and found it very inspirational!”

In 2019, Carrying The Fire was re-released with an updated preface in which Collins reflected on his life. His wife of 57 years, Patricia Mary Finnegan Collins (whose mother was born in County Mayo), had passed away in 2014, but that sad event aside, Collins wrote that his life was “fun and fulfilling in many ways. Watching my family grow, all doing well, has been paramount, but beyond that come fishing, reading, chasing the stock market, and exercise, exercise, exercise.”

Collins also expressed immense interest in future plans to explore Mars, and conveyed enthusiasm for investment from the private sector, saying men like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos who can make anything cheaper and faster, may also be the people who can make reaching Mars a reality.

He was an adamant supporter of a well-rounded education and continued to visit universities throughout his life – MIT being his go-to place. When it came to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), Collins believed that while imperative, it was not a complete education in itself. He suggests adding English as a pillar to make the acronym STEEM, stressing that if proper knowledge on how to effectively deliver a message is never learned, it won’t matter what the equations express.

When asked the question on everyone’s mind in 2019, as America marked the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11’s blast-off. “How was the Moon?” – Collins reflected, “My primary recollection is not that of the Moon. It is of the Earth as seen from 230,000 miles out…it’s a fragile place and we need to do a better job of taking care of it.”

Michael Collins is survived by two daughters, Kate and Ann, seven grandchildren and a sister. His wife, Patricia died in 2014, and their son, Michael, in 1993.

The following is a statement from the Collins family:

“We regret to share that our beloved father and grandfather passed away today, after a valiant battle with cancer. He spent his final days peacefully, with his family by his side. Mike always faced the challenges of life with grace and humility, and faced this, his final challenge, in the same way. We will miss him terribly. Yet we also know how lucky Mike felt to have lived the life he did. We will honor his wish for us to celebrate, not mourn, that life. Please join us in fondly and joyfully remembering his sharp wit, his quiet sense of purpose, and his wise perspective, gained both from looking back at Earth from the vantage of space and gazing across calm waters from the deck of his fishing boat.” ♦

To read more about Colonel Michael Collins and the space program read Patricia Harty’s interview with Colonel Eileen Collins from 1999.

Interested in learning more about what it took to get to the moon and the people that contributed? Read Tom Deignan’s review of American Moonshot by Douglas Brinkley.

Leave a Reply