What a difference two decades make

By Megan Smolenyak

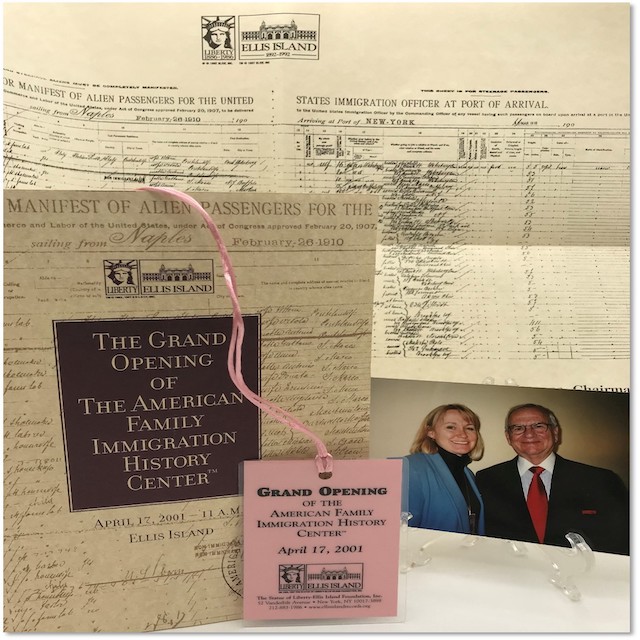

In April of 2001, a miracle occurred. Well, it certainly seemed that way at the time. The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation (SOLEIF) opened the American Family Immigration History Center (AFIHC), launching an online database — digitized and indexed — of the passenger records of millions of immigrants who took their first steps in America at Ellis Island.

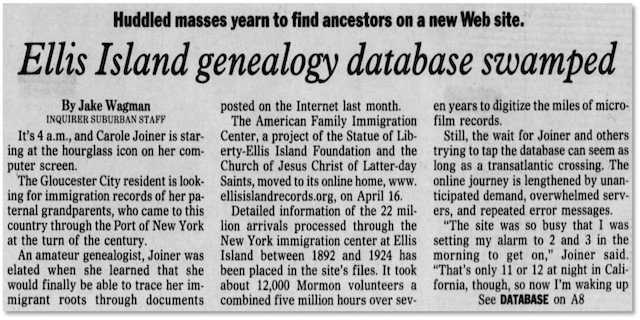

Fast forward 20 years, and we expect genealogical companies to provide fresh databases weekly, but I’d like to try to convey what a big deal this was. It was — quite literally — national news. Don’t believe me? Here’s proof:

SOLEIF had partnered with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints which transcribed the massive dataset. 12,000 volunteers had taken seven years — five million man hours — to wrestle with and interpret the handwritten documents so we could surf in our pajamas to find our ancestors’ arrivals. And once we did, we could click right through to see the actual record — for free! This was revolutionary.

Time Travel

Please indulge me as I travel back in time to describe the process today’s genealogists no longer have to endure. To find the immigrants in their family tree, researchers had to already have an approximation of when a given ancestor arrived, physically go to the National Archives or one of the limited repositories scattered across the U.S. that housed these records on microfilm, use Soundex, and then scroll through in the hope of spotting their target. And heaven help you if your name “coded common.” This meant that if the Soundex code for your surname was, say, M530, you would have to sift through the countless Smiths to find your Smoot in their midst.

Once you did, the information provided would steer you to another roll of microfilm that held the passenger record. More mindless cranking until your wrist hurt (only the most upscale of repositories had readers that enabled users to electronically speed forward or backward). If you were lucky, you had a list and/or line number to help spot your prey among the many, but this wasn’t always the case. And once you found what you were looking for, you couldn’t simply take a photo since this was pre-cell phone. In fact, readers that printed were so expensive that most facilities only had a couple, so in most instances, you would have to remove the film, take it to a dedicated printing-reader, reload it, slips some coins in, and only then, get your image.

Those who were skilled and fast might be able to obtain a record in 30 to 45 minutes, provided there were no hiccups, such as a spelling that bumped the surname into another Soundex code — which often happened with names like Smolenyak. But so many were the speed bumps along the way that most genealogists had a cluster of ancestors who had proved elusive.

But weren’t there already genealogical databases online? Yes, both Ancestry and FamilySearch existed and were searchable, but most back then were transcriptions. Only a modest portion were linked to digitized records, and until this moment, immigration data was patchy at best. So radical was all this that I recall (having the advantage of insider knowledge) telling a renowned immigration guru about this imminent online release just months earlier, and while he was gracious, it was clear that he thought I was fantasizing. I can’t fault him because — in the context of the times — what I shared with him sounded like insane wishful thinking.

Crash and Recovery

So what happened upon launch? It crashed. And I mean badly, as this “Huddled masses yearn to find ancestors on a new Web site” article demonstrates.

Demand was so great that the database logged eight million visitors in its first six hours — this in an era when many were not yet online. It took just 54 hours for the number of page views to exceed the number of immigrants who passed through Ellis Island in the 32 years (1892–1924) covered in the launch (later expanded to 1820–1957).

Making this all the more astounding were the millions of us who tried, but couldn’t get in. Dedicated genealogists across the country set their alarms for 3:00 a.m. EST to improve their chances of completing their searches. To their credit, SOLEIF responded swiftly, adding servers at a serious clip, but even a month later, we were rising early to gain access. Eventually, the fresh servers caught up with demand and researchers could dive in at any hour.

Raise a Glass!

I hope I’ve managed to convince at least a few how fortunate we are to be able to take all this for granted. Next time you find yourself digging for traces of your great-great-grandfather, spare a thought for the good folks at SOLEIF who brought us the Ellis Island database and set the standard for what was possible. Thanks for joining me on this meander through genealogy’s not-so-distant past — and also, I hope, in toasting their special anniversary.

Megan’s Pro Tip: No luck finding your ancestor? Use Steve Morse’s search tool to help unearth those who might be hiding under unexpected spellings or other misleading details.

Megan Smolenyak is a genealogist and the author of six books, including Trace Your Roots with DNA and Who Do You Think You Are?, a companion to the TV series. She prefers to call herself an incurable genealogist and sometimes author. Her articles for Irish America, include a piece that she wrote about her decade-long search that finally turned up the Irish cousins of Annie Moore of Ellis Island fame. She also brought to light the Irish heritage of President Joe Biden, President Barack Obama, and such celebrities as Bruce Springsteen, Jimmy Fallon, and Stephen Colbert. Her most recent genealogical detective work has rooted out the Irish ancestors of Barry Manilow. Her articles for the magazine also include such hidden discoveries as, “The Spy in the Castle,” which concerned the Dublin Metropolitan Police officer and Michael Collins spy David Neligan. Follow Megan on Twitter @megansmolenyak or visit her website www.megansmolenyak.com to learn more.

Megan Smolenyak is a genealogist and the author of six books, including Trace Your Roots with DNA and Who Do You Think You Are?, a companion to the TV series. She prefers to call herself an incurable genealogist and sometimes author. Her articles for Irish America, include a piece that she wrote about her decade-long search that finally turned up the Irish cousins of Annie Moore of Ellis Island fame. She also brought to light the Irish heritage of President Joe Biden, President Barack Obama, and such celebrities as Bruce Springsteen, Jimmy Fallon, and Stephen Colbert. Her most recent genealogical detective work has rooted out the Irish ancestors of Barry Manilow. Her articles for the magazine also include such hidden discoveries as, “The Spy in the Castle,” which concerned the Dublin Metropolitan Police officer and Michael Collins spy David Neligan. Follow Megan on Twitter @megansmolenyak or visit her website www.megansmolenyak.com to learn more.

Leave a Reply