How Flannery O’Connor’s upbringing and her Irish Catholic heritage impacted her writing.

O’Connor’s great-great-grandfather, Patrick Harty, came to Georgia in 1824 from County Tipperary, settling in Taliaferro County. His Irish-born daughter Johannah, who became Flannery O’Connor’s great-grandmother, married Hugh Donnelly Treanor in 1848. Hugh had also emigrated from Tipperary, and moved in 1833 to Milledgeville, where he bought and operated a grist mill. He was one of the first Catholics in the area, and the first mass in Midgeville was said in his hotel room. When he died, his widow Johannah Harty donated the land on which Sacred Heart Catholic Church was built in 1874.

Johannah and Hugh’s daughter, Kate, married Peter J. Cline, a prosperous dry-goods store owner in Milledgemille, who also had Irish roots. When Kate died, Peter married her sister, Margaret Ida, and they had 16 children, including Regina who became Flannery O’Connor’s mother.

Regina married Edward O’Connor of Savannah in 1922. Like his wife, he had Irish Catholic roots. His grandfather emigrated from Ireland in 1851 and established a livery stable on Broughton St. in Savannah.

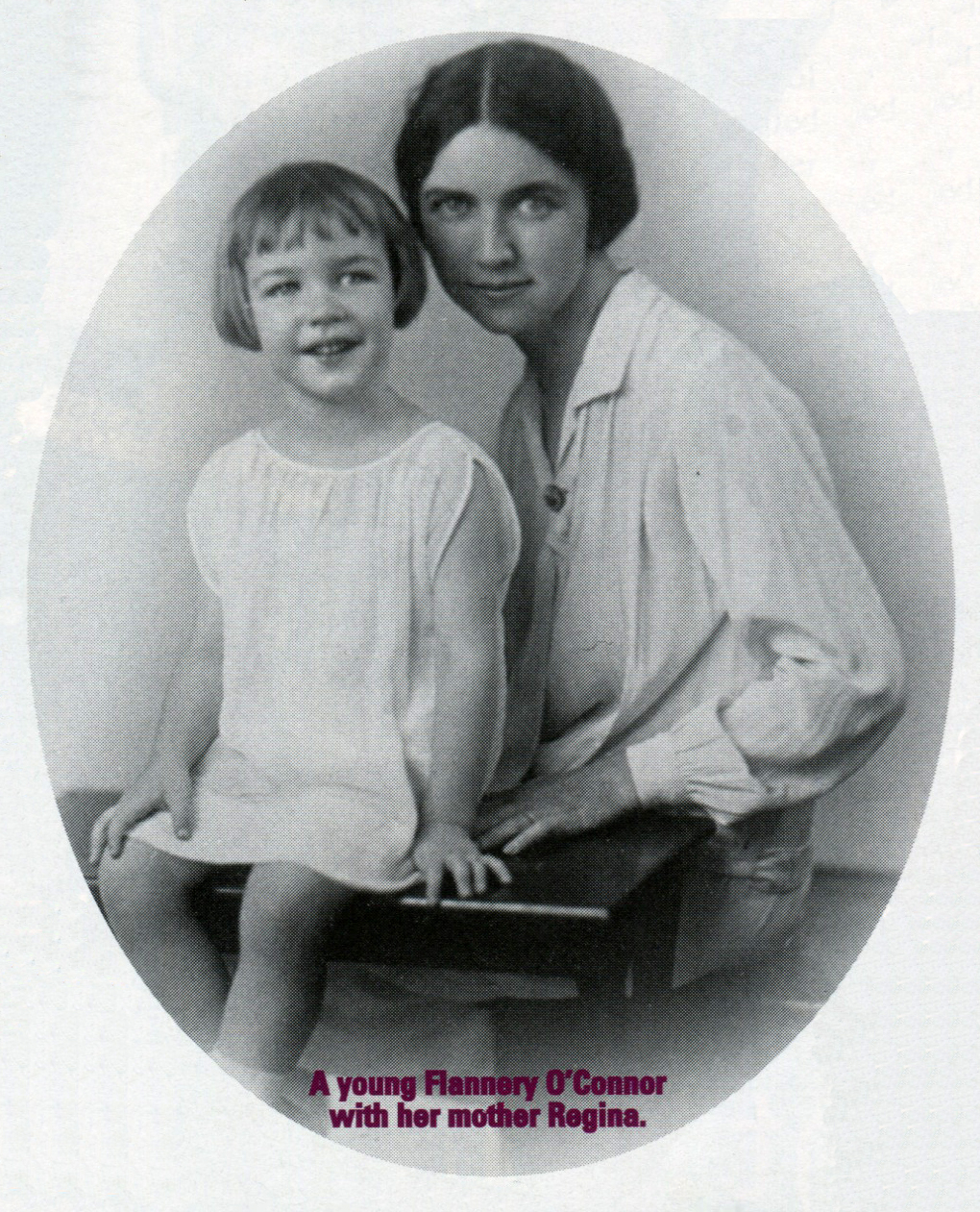

In time, Edward and Regina became the parents of a girl whom they christened Mary Flannery O’Connor. She was named for her cousin Katie Semmes’ mother, Mary Ellen Flannery, the wife of decorated Confederate army officer, John Flannery, who had also immigrated from County Tipperary (Nenagh).

Flannery, an only child, spent her early years in Savannah, where her home is now a historic site. In 1938, when O’Connor was 13, her father moved to Atlanta for work, and she and her mother moved to Milledgeville, to the Cline family mansion, where Regina had grown up. Edward returned home on weekends. Flannery adored her father, but when she was 16, he died of lupus, the disease that, years later, killed her.

O’Connor attended local Catholic schools and then Georgia Women’s College in Milledgeville. In 1945 she received a fellowship to the Writer’s Workshop at the University of Iowa, from which she received a M.A. degree in 1947. While still a student, she wrote stories that caused her to be recognized as a writer of considerable talent. It was around this time that she dropped her first name and became known as Flannery. After a stay at Yaddo, the artists’ colony in upstate New York, O’Connor moved to a furnished room in New York City. Later, she lived and wrote in an apartment over a garage at the Connecticut home of Sally and Robert Fitzgerald, who became after her death, her literary executors.

In December 1950, O’Connor experienced a heaviness in her arms. On the train trip home from Georgia for the Christmas holiday, she became so ill she had to be hospitalized. The cause of her problems was diagnosed as disseminated lupus.

O’Connor not only suffered from the disease itself – which caused her muscles to weaken and her body to swell, among other things – but from the medicine she took to fight it, which caused her hair to fall out and other problems.

O’Connor’s comments on her illness were often humorous, sometimes merely descriptive, occasionally philosophical, almost never self-pitying.

In the fall of 1951, after spending nine months in a hospital, she returned to Milledgeville. Because she could not climb the stairs, her mother brought her to their country home, Andalusia, which is located about five miles from town.

Outside the house, everything clucked and gamboled with life: ducks, geese, turkeys, pheasants, swans and chickens of every description. Her uncle, Louis Cline, kept her supplied with feathery exotica, including peacocks. When Andalusia was in the bloom of life, these kings and their queens roamed everywhere, choosing their roosts, fencepost and branch of the surrounding trees. To a visitor, O’Connor once pointed out that the peacock was, in medieval times, considered to be a symbol of the Transfiguration of Jesus.

O’Connor was an unappreciated prophet in her home town. A physician who worked in the local mental hospital read her novel Wise Blood and commented: “I enjoyed it, but I know one thing for sure. She don’t know a damn thing about a whorehouse.” Flannery later admitted she had leaned on conjecture in her Wise Blood brothel episode.

She was jovially critical of the Irishness of the Milledgeville and the way the Irish-American pastor draped the church in green on St. Patrick’s Day. She was less jovial in her criticism of what she called the Irish cast of American Catholicism of her time.

The only activity that took O’Connor away from Milledgeville during the last decade of her life was her lecturing and reading from her work in colleges. Lecturing was also a source of income as she earned little from her books. She never gave the same lecture twice; she always worked over her notes, adding here and subtracting there.

Her Ideas and Her Writing

Central to O’Connor’s life and writing was her Catholic faith. It was rigorous and unsentimental. “I take the Dogmas of the Church literally,” she wrote in one letter. “Dogma,” O’Connor said, “is the guardian of mystery. The doctrines are spiritually significant in ways that we cannot fathom.”

While she believed in all the mysteries of her faith, she was incapable of writing dogmatic stories. No religious tracts, nothing haloed by celestial light, nor happy endings. Not only does ‘good’ not triumph, it is usually not present. And God never intervenes to help anyone triumph.

To novelist friend John Hawkes, she wrote: “People are always asking me if I am a Catholic writer. I am afraid that I sometimes say no, and sometimes say yes, depending on who the questioner is.”

On August 2, 1955, she wrote: “My audience are the people who think God is dead. At least these are the people I am conscious of writing for.”

O’Connor knew the difference between art and religion, and never confused the two subjects. She understood that her primary duty was to tell an engaging story. ♦

A version of this article was first published in Irish America in April 1998. Additional information on Flannery O’Connor’s roots was provided by http://andalusiafarm.blogspot.com/

Editor’s Note: In 2016, Howard Keeley, the director, of the Center for Irish Research and Teaching at Georgia Southern University invited me to speak to his students at GSU. He also arranged for me to meet the descendants of Patrick Harty who had immigrated from my home county, Tipperary, in 1824.

The Harty Abbots couldn’t have been more welcoming. They treated me like a long-lost cousin and welcomed me to their home. They are still very interested in their roots and involved with Irish heritage projects in Savannah. Jane Harty Abbott regaled me with stories of a trip that she and her husband took to Ireland in which they met up with Michael Harty bishop of Killaloe and other relatives.

Sadly, Jane Harty Abbott passed away in May 2020. In 2010, following the death of her husband, she had established the Laurie K. Abbott Endowment Fund at the Georgia Historical Society, ensuring that their shared dedication to Georgia history education would continue in perpetuity. With her passing the family chose to add funds to and rename the fund in honor of both parents as the Laurie Kimball and Jane Harty Abbott Fund with an additional $500,000 gift. – P.H.

Stream the PBS documentary, “Flannery” on your local PBS station.

Patricia,

Thank you for the recognition extended during your prior visit with Jane Harty Abbott in Savannah. It was indeed an unexpected pleasure to be inducted into the Irish America Hall of Fame. Since your prior visit we

have been privileged to be involved with Dr. Howard Keeley’s Center for

Irish Research and Teaching at Georgia Southern University and see the

development of a GSU Campus site in County Wexford Ireland. Having

both of my paternal great grandparents immigrants from Wexford to Savannah in the 1850’s makes the award even more cherished.

Frank

Flannery O’Connor was a brilliant writer who illustrated the power of Grace in human lives. Her stories were tough, funny, and often violent but suffused with compassion. She was a great Bard in the Irish tradition. I am proud to share her Irish heritage.

I was happy to read this article about Flannery O’Connor and about Patrica’s connections to her Harty relatives! You come by your love of Ireland, America and Irish Americans honestly!