An exhibition tells the story of an interracial community destroyed to make way for New York’s Central Park.

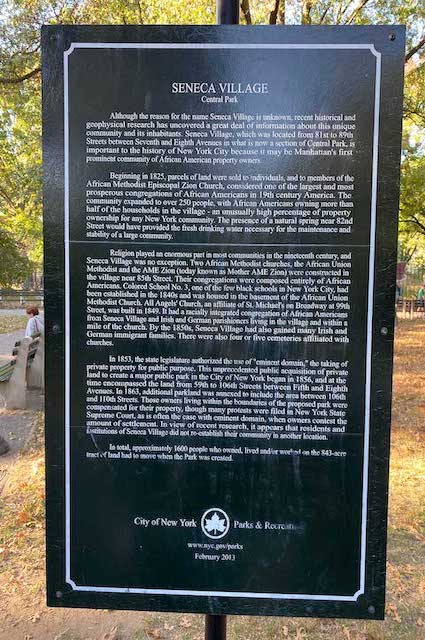

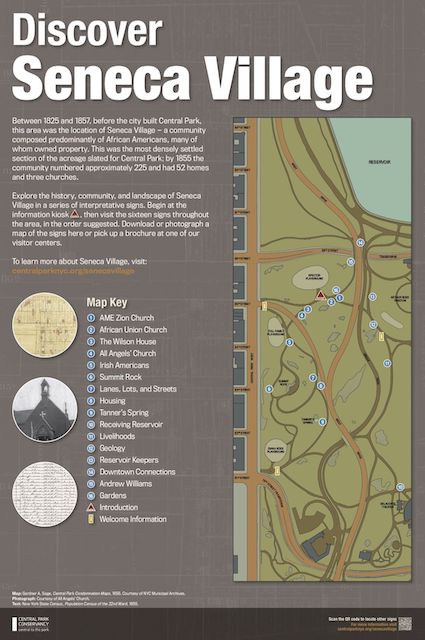

Dog walkers and joggers nonchalantly stepping over the barely visible cobblestones embedded in a grassy patch in New York’s Central Park have no idea that those stones were church foundations of a once prosperous enclave called Seneca Village. Begun in 1825 by African-Americans and later joined by Irish and German immigrants in the 1840s, the community thrived until 1857, when wealthy merchants decided New York needed a municipal park — one to rival those of Paris and Vienna. The 30-odd-year history of Seneca Village, which was, in fact, the largest and most prominent of many Central Park settlements, is chronicled in an intriguing exhibition at the New York Historical Society.

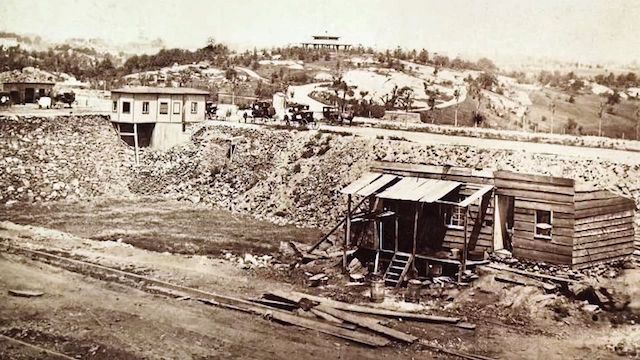

Newspapers of the day, however, painted a different picture of Seneca Village. Reporters willing to overlook the people living there because the park was supposedly for “the greater good of the public” characterized the land-owning, tax-paying inhabitants as “insects” living in “shanties,” and the village was referred to as a “nuisance…best removed in the name of progress.” The New York Times wrote of the “large number of rickety little one-story shanties and mixed population of squatters, mostly Irish (one third of the population of Seneca), and pigs, goats, chickens, cows and children. The whole thing was an excrescence on the fair features of the City.”

Peter Quinn, who wrote Banished Children of Eve, a historical novel detailing the Irish in New York in the 1860s, describes Seneca Village as “part of the unwritten history of the Irish and African-Americans. They didn’t have power, so they didn’t have a chance to write their history.”

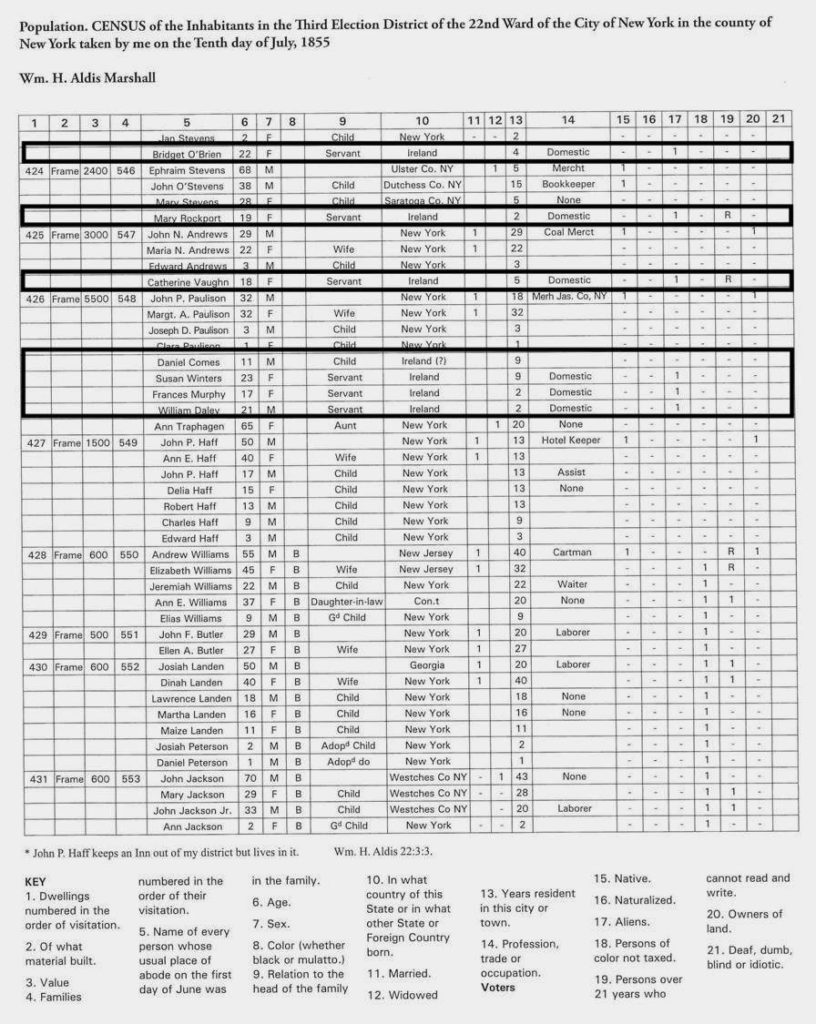

In reality, church and census records indicate that the residents of Seneca Village (roughly from 82nd to 88th Streets near Central Park West) were hard-working families with strong community bonds. There were three churches, two schools, and two cemeteries. The villagers worked as domestics, gardeners, laborers, dressmakers, and teachers. Documents from the era – including records of an interracial marriage — suggest that the races in Seneca Village were comfortably integrated. An Irish woman named Margaret Geery was the midwife for the entire village. John Geary had the prestigious job of maintaining the nearby Croton Reservoir, and two Irish lads, George Washington Plunkitt and Richard Croker, eventually held influential positions in Tammany Hall.

But when authorization for the park came in 1853, the villagers, with no real money or power, could do little against the powerful men with large estates who had the ears of the city planners. According to a local paper (March, 1856), the villagers were “notified to remove by the August 1st,” and were meagerly compensated for their property. Those who resisted eviction were beaten by local police. In a cruel twist of irony, many of the evicted Irish were then hired to landscape the park — a job that black people were not permitted to do.

Sadly, there are no records of what happened to the Seneca Village residents; no living descendants have been located, although Historical Society curators are trying to change that. Slowly, they are piecing together the lives of the few hundred people who called Seneca Village home.

Explore the history of this area with Discover Seneca Village, a temporary outdoor exhibit of interpretive signage that gives visitors a glimpse into this fascinating community. To view the exhibit, enter the Park at Central Park West and West 85th Street. Maps will guide you to the locations of the signs. You can also download a map before you go or pick up a brochure at any visitor center. Signage will be on display through Fall 2021.

You can also now explore Seneca Village’s history from the ease of your phone via the Bloomberg Connects app or download the signs to learn more.

The Central Park Conservancy will be hosting virtual tours of Seneca Village beginning March 9, 2021 through June 15, 2021. To find tour dates and book your tour visit Central Park Conservancy website.

Note: An earlier version of this story appeared in Irish America in April, 1997.

My grandmother told me about her family being scammed out of compensation for their ownership in what is now central park. She was Irish. Legal teams asked all the family members to sign off any rights. Their money was never received.

Ancestor shows up in 1855 census in this web page. My grandmother was Irish.

There were 3 churches and 2 cemetery meaning there were dead buried…. r u telling me that visitors of Central Park are walking on top of the dead ???? There is nothing on Google or history anywhere if the bodies of the dead had been dug up and relocated ??? Most of the Seneca village populatiom were African American that’s why noone really cares to dig up the dead! If only those black attorneys prosecuting trump would go after their history and NY ….

Seneca Village’s history serves as a powerful reminder of the contributions of African Americans to the development of New York City and the United States.

The village played a vital role in the cultural and social life of its residents, offering a place for education, worship, and community gatherings.