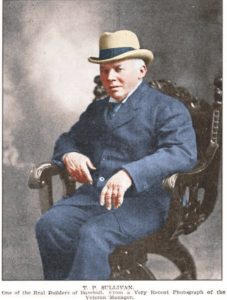

Although almost completely forgotten now, Ted Sullivan (1848 – 1929) was once among the best-known characters in baseball. He was called “The Daddy of Baseball” and “The Godfather of the National Game.” His story touches dozens of American cities, from Chicago to Washington D.C., Milwaukee, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Dallas, where he managed teams, started leagues, scouted players and charmed chamber of commerce executives anxious to put a team in their town.

In his day, Irish-born T.P. “Ted” Sullivan was considered the best baseball mind in America. Some went so far as to call him “The Godfather” of the sport. He was early baseball’s town-hopping bandleader; the ringmaster of the minor leagues; a George Washington, a Harold Hill, and a P.T. Barnum all rolled into one.

He was described by one old-time sportswriter as “a red-cheeked, sturdy little Irishman…good-natured, crafty, a chatterbox when wound up, very proud of his ancestry and himself.”

From the late 1860s until the day he died in 1929, the cunning, fast-talking, witty, charming, serious and sober Sullivan traveled more than a million miles in horse-drawn buggies, soot-spitting trains and lumbering steamships to spread the gospel of his beloved sport across the breadth of North America, Europe, Asia, and South America.

The second child of Mary (née Blakeney) and Timothy Sullivan, Sr., Timothy Paul a.k.a. “Ted” was born in 1848 in County Clare, in the depths of an Gorta Mór – “The Great Hunger,” and at age six or seven accompanied his parents and siblings to America. The family settled in Milwaukee, where Ted attended St. Gall’s Catholic school and fell in love with his new country’s national game on the sandlots of the beer town’s Irish-heavy Third Ward.

It was at college, in tiny St. Marys, Kansas, where Sullivan was wed to the game for life. A whip-smart student and a pretty fair pitcher, the red-headed Irish boy ruled the school’s ballfield roost as captain of the St. Mary’s Saints baseball team. He was pitching and playing shortstop his senior year, in 1874, when he took a 15-year-old freshman named Charlie Comiskey under his wing – a friendship that would one day take them both around the world, and the latter to the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Charlie’s father, “Honest John” Comiskey, the powerful Chicago alderman, and Irish-born president of Chicago’s Sons of Erin, considered his son’s “baseballitis” disgraceful, and threatened to all but shoot Sullivan for putting young Charles under his spell. But Ted and Charlie stuck together, moving to Dubuque, Iowa, where Ted formed what is often considered the first “minor” league. It was as player/manager for the Dubuque Rabbits, a Northwestern League team that dominated even major league opponents, that the innovative Sullivan taught young Comiskey to play first base, stationed off the bag for better defense, as all first-sackers do today.

Bugs, Cranks, and “Fans”

In his frustration with loud and know-it-all spectators, Ted Sullivan took to calling them “fanatics,” or “fans” for short.

It was while managing the great St. Louis Browns team of 1883 that an exasperated Sullivan blurted out the term that would become a staple in the vernacular of sports fanatics throughout the world.

Sullivan would recall that he, Comiskey and a group of other players became annoyed at a bloviating crank who had infiltrated the clubhouse to offer his advice on how the game should be played. After the offending party departed, Sullivan reportedly said that he’d not be told what to do “by a lot of fanatics. I’ll call them ‘fans’ for short.”

He Took Baseball to Ireland

Throughout his life, Sullivan would wax eloquently and often as to the superiority of Irish players in America’s great game. One of his most fervent and recurring dreams was to take a couple of American ball teams to Ireland for a series of exhibitions and demonstrations. He believed young Irishmen schooled in the ancient sport of hurling (or “shinty,” as he called it), made natural baseball players and that once they saw and learned the game, they’d follow the rainbow to paycheck gold in America.

On his first of many visits to the land of his birth, Sullivan organized a game of baseball on the lawn of Ross Castle. The British tourists who participated hated the game. The local Irish liked it, but couldn’t figure out the rules.

In late 1888, he announced a plan to arrange an “Irish Green Stockings” team to inaugurate the game in Ireland. Armed with a steamer trunk full of Spalding baseballs and bats, he was able to organize a baseball game between a band of locals and a contingent of cricket-playing English tourists on the shore of Killarney’s lower lake. The game took place on a loosely cropped cow pasture with 15th century Ross Castle looming in the background.

“The English parties quickly got disgusted and said the blooming Yankee game was sillier than marbles or mumble peg,” remembered Sullivan. Finally, a local Irishman – Michael Dempsey, “the crack hurler of County Kerry,” according to Ted – proceeded to wield the “cudgel” and drove one of the Spaldings off the shin of the English pitcher. The game at that point fell apart, with the English pitcher grousing “ I wisht that blowsted, blooming Yankee and his blowsted, bleeding game was sunk in the middle of the blooming ocean before he came over here.”

“Ted Sullivan needs no introduction to baseball fans, for to introduce him would be to introduce baseball itself. Mr. Sullivan is so well known in the baseball world that if you should in the blissfulness of your ignorance plaintively ask, ‘Who is Ted Sullivan?’ you would thereafter be shunned and avoided as a person of unsound mind.”

Abilene (Tx) Daily Reporter, March 25, 1920

Saw the Coming of Soccer

In 1894, baseball’s magnates saw the game of soccer was packing stadiums across Europe with wildly enthusiastic, money-waving “fans.” With cities along America’s eastern seaboard teeming with first- and second-generation European immigrants, the idea of putting league soccer on America’s baseball fields in the winter months was born. T.P. Sullivan was picked as the midwife to raise it up.

That fall, while the attention of America’s baseball men and their fans was focused on the pennant races and the World Series, Sullivan quietly slipped aboard a ship headed for the British Isles. His mission: to surreptitiously find, recruit and bring back a crack team of soccer players for the Baltimore Orioles’ entry into America’s new professional soccer league.

Sullivan’s ringers so dominated the fledgling league that fans soon lost interest and America’s first “major” soccer league folded after just one season. Still, he maintained the sport had unlimited potential, and that bringing it back for another go would “render a service to the sport-loving people of America and give work to hundreds of lively youths.

“‘Mark me,’ he said. ‘People will take to it.’”

One innovation that Sullivan never would have allowed himself to foresee was the inclusion of African Americans in America’s favorite sport. Like most players, managers, owners, cranks, and fans of his day, Ted Sullivan was a dedicated adherent to the notion of American – specifically white male – exceptionalism. But he predicted, “someday other ethnic groups in America might be invited to play in similar competition,” including “that sport-loving people, the Hebrews, who are today the staunchest supporters of the national game,” the Italians, “who have already shown their castor in the prize ring,” and even “the colored race, which has been represented by excellent men, namely Walker, Stovey and Grant.”

A Worldwide Reputation

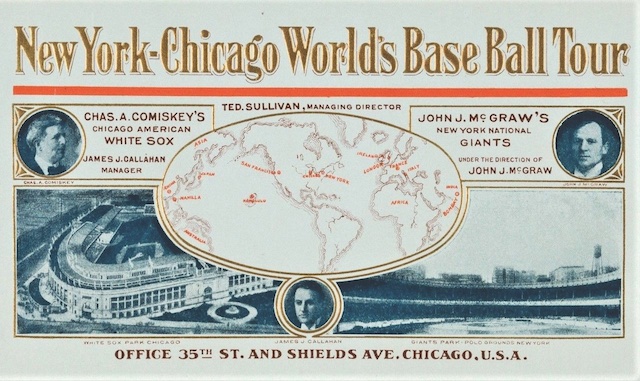

Over his long and colorful life, the irrepressible Sullivan wore a closetful of hats – as player, manager, scout, broker, promoter, sportswriter, author, baseball historian, lecturer, and after-dinner speaker. But he found his most lasting fame as an organizer of ambitious baseball roadshows. He took the White Sox on a heralded exhibition tour through Mexico in 1907. But his coup-de-grace was the arrangement and management of “The World’s Tour of Baseball” in late 1913 and early 1914.

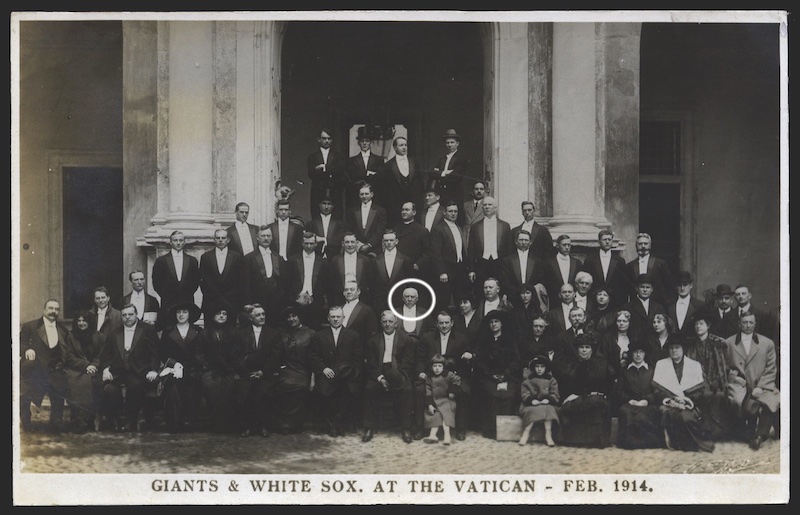

As Tour Directorate, he led a parade of high profile ballplayers from the Chicago White Sox and the New York Giants through the Middle East, Asia, Australia, and Europe, garnering headlines and making a pile of money for team owners Comiskey and Harry Hempstead.

In the above photo, taken at the Vatican, Sullivan is the white-haired gent seated in the middle of the second row, behind Charlie Comiskey.

For the many Irish Catholics on the tour, visiting Rome and receiving an audience with Pope Pius X was the highlight of their trip. “Nothing was more imposing to us all, irrespective of the creed of members of the party than the entrance, to the room in which we were seated, of this grand old man of the Roman Catholic Church,” recalled Sullivan. “His beautiful, classic face, his manner of giving us his blessing, impressed all very much.”

Slapped with a Black Card

Timothy P. “Ted” Sullivan’s last great scheme was to bring Ireland’s heroes, County Kerry’s famed Gaelic football champions, to the United States in 1927 for a series of exhibition matches designed to raise funds for GAA facilities and programs back in Ireland. But the football scheme got off on the wrong foot right off the bat, with the Irish heroes getting beat by a crack team of Irish ex-pats in front of 30,000 people at the Polo Grounds in New York.

Timothy P. “Ted” Sullivan’s last great scheme was to bring Ireland’s heroes, County Kerry’s famed Gaelic football champions, to the United States in 1927 for a series of exhibition matches designed to raise funds for GAA facilities and programs back in Ireland. But the football scheme got off on the wrong foot right off the bat, with the Irish heroes getting beat by a crack team of Irish ex-pats in front of 30,000 people at the Polo Grounds in New York.

The Kerry stars were treated like visiting potentates before playing local sides in Boston, Hartford, New Haven, and Chicago, but ticket sales fell well short of goal. Toward the conclusion of the tour, Irish tempers flared after the touring party discovered that Sullivan had abandoned them and absconded with the Irish team’s $11,000 share of the gate receipts.

Strike Three

Two years later, the man who a generation of sports writers called “The Daddy of the Game” died alone and largely unnoticed in Gallinger Hospital in Washington, D.C. He was 78.

America and baseball then went on to pretty much forget all about Timothy Paul “Ted” Sullivan. He is interred in Calvary Catholic Cemetery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. ♣

Note: Pat O’Neill and Tom Coffman spent nearly four years, and unearthed and reviewed more than 2,000 old newspaper and magazine articles, journals, and books in order to piece together the story of Ted Sullivan’s colorful and prolific life in baseball. Their book, Ted Sullivan, Barnacle of Baseball: The Life of the Prolific League Founder, Scout and Unrivaled Huckster, is available from McFarland & Co. in early 2021.

Leave a Reply