In 1876, a daring escape from an Australian prison colony by six Fenian prisoners was masterminded by the revolutionary and journalist John Boyle O’Reilly.

The sailing triumph of the Catalpa and the daring escape of six prisoners from an Australian prison dates back to 10 years earlier, 1866, to the failure of the Fenian rising in Ireland, when they were among those arrested and convicted of treason by the British government.

All these men were members of the British Army and had served Queen Victoria’s government with distinction in India, China, Syria, and South Africa. When they were eventually posted in Ireland, all joined the Fenians.

In this they were not alone, for in 1865, of the 26,000 regular troops of the British Army stationed in Ireland, 8000 were members of the Fenians, sworn to lead a national uprising to free the Irish people from 700 years of oppressive British colonial rule.

But that rebellion or “rising” was doomed to failure – crushed from outside by the pervasive power of the British government and betrayed from within by the treachery of Irish informers. In September 1865, the British authorities rounded up the most prominent civilian leaders of the Fenians, and the spirit of the rebellion was effectively destroyed. By February 1866 the organization slowly disintegrated as arrests of soldiers and civilians became a daily occurrence.

Among the 68 members of the Fenians who were tried and convicted in the summer of 1866, we’re 15 members of the British army. The sentences for the civilians were harsh – 15 to 20 years of penal servitude. But for the military Fenians, the sentence was worse – death.

The Irish prisoners were dispatched to serve their terms in the horrors of the infamous English prisons of Dartmoor, Millbank, and Portland. After they had served the mandatory six months of solitary confinement, the prisoners’ sentences were commuted. For most civilian Irish convicts, the penalty was downgraded to banishment from the British Isles. For the military members of the brotherhood, the death sentence was changed to penal servitude in Western Australia – for life.

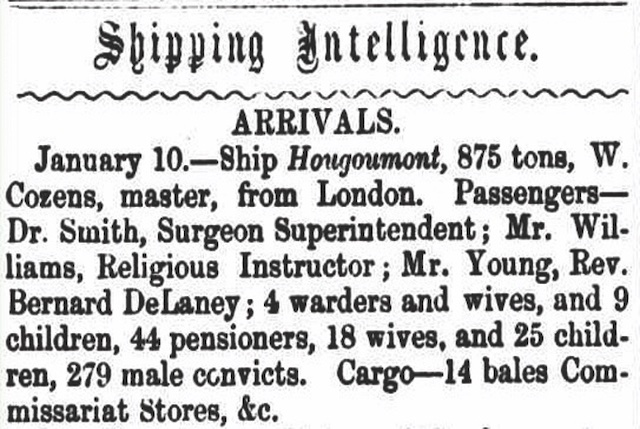

On the morning of October 12, 1867, the final group of 20 prisoners, manacled in arm and leg irons, were loaded aboard, and the prison ship Hougoumont set sail from Portland Harbor in the English Channel. Below deck were 320 criminal convicts and 63 Fenian political prisoners.

The 15 military members of the Fenians were placed with hardened criminals – murderers, thieves, and rapists. Although life was harsh, they were at last free of the physical restrictions of the chains and the emotional despair of solitary confinement.

Three months later, Hougoumont arrived in Fremantle. As the prisoners disembarked, they saw before them a large limestone building overlooking a few wooden frame structures that led down to the waterfront. That building, the Fremantle Jail, had become the main reason for the existence of the city of Fremantle and was known throughout the countryside as the “Establishment.”

The prisoners were marched up the hill, and as the iron gates of the Establishment shut behind them, they were given a number and told that for the period of their confinement they would no longer be identified by name but by the impersonal four-digit code. The warden then read off a long list of prison regulations and the recitation of each stringent rule was punctuated by the consequence of failure to comply – “…The punishment for a which is death.”

The prisoners spent their days performing the back-breaking labor of clearing land, digging roads, and building public service utilities and governmental structures in Fremantle and in Perth, the new capital of Western Australia. At night prisoners were crammed into cells, four feet by seven, by nine feet high. The security was tight but the confinement in the cells and the frequent wardens’ checks were hardly necessary. They were far less intimidating than the geographical barriers around them.

On three sides the Establishment was surrounded by the Australian bush – an uncharted expanse of desert and scrubland without a source of food or water and sparsely populated by hostile aborigines. Escape through the bush was impossible and the man who was foolish enough to try it faced a slow but certain death. To the west lay the Indian Ocean – an exotic, unpredictable sea whose natural defense lay in its shark-infested water close to shore, and, beyond that, its immensity – for due west the closest landfall was Africa, 4,700 miles away. Western Australia was a maximum-security prison where nature was both the jail and the jailer. There was no way out.

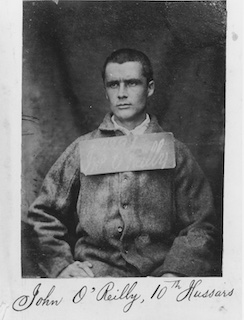

Then John Boyle O’Reilly escaped. In a way, it wasn’t a surprise to his fellow prisoners. O’Reilly had been the only one to escape England’s Dartmoor prison and, although he was recaptured two days later, his fellow Irish prisoners knew he was serious when, upon landing in Fremantle, he promised he would be the first to escape from the Establishment.

His disappearance, however, was a shock to his jailers. Although he had the record of an almost successful prisoner escape, his tender age, his short stature, his youthful face (as yet unencumbered by whiskers) and his gift for poetry hardly made him seem a threat. On the contrary, soon after his arrival, he was put in a position of minimum security from which he could now effectively plan his escape.

The plan involves a nighttime dash through the woods and, assisted by an Australian benefactor, a 40-mile pull in a rowboat to intercept an American whaling vessel. When the first whaler didn’t pick him up as promised, O’Reilly spent another two days and nights without food or water, rolling in the Indian Ocean looking for a friendly vessel. After five more days of hiding on the shore, his contact arranged for another American whaler to pick him up. This time it worked, and after a journey of nine months, John Boyle O’Reilly arrived in America.

Back in the Establishment, the prisoners knew only what was reported in the Police Gazette, “that imperial convict number 9843 absconded from Convict Road Party, Bunburry, on the 18th of February, 1869.” No one suspected that he had survived. Many others had run away and those who were not captured were never heard from again – victims of sharks and the bush.

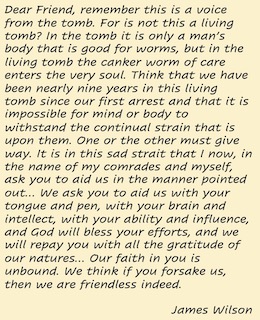

A year later, letters arrived from America and Ireland saying O’Reilly was alive. He had made it! Hopes were buoyed. Letters poured out from Fremantle begging for help.

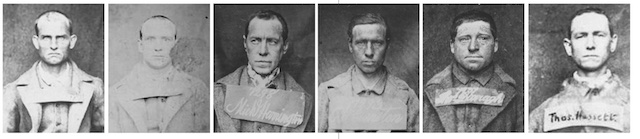

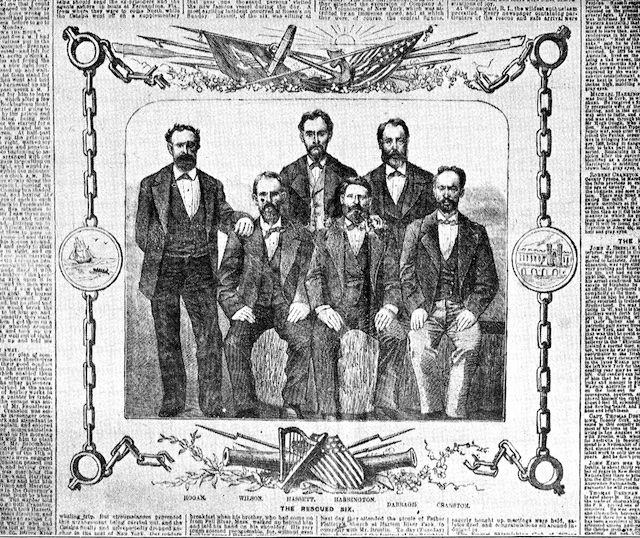

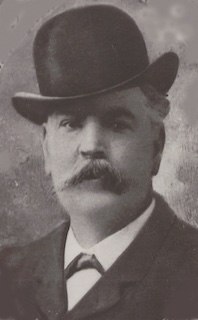

Years went by. Some prisoners were released. Others died. The letters were never answered – there was no solution to those appeals for help. For one man to get out was a miracle. For the six remaining military prisoners to get out was impossible. The six – Hassett, Wilson, Darragh, Harrington, Cranston, and Hogan – knew that they were the forgotten men

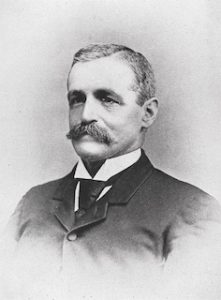

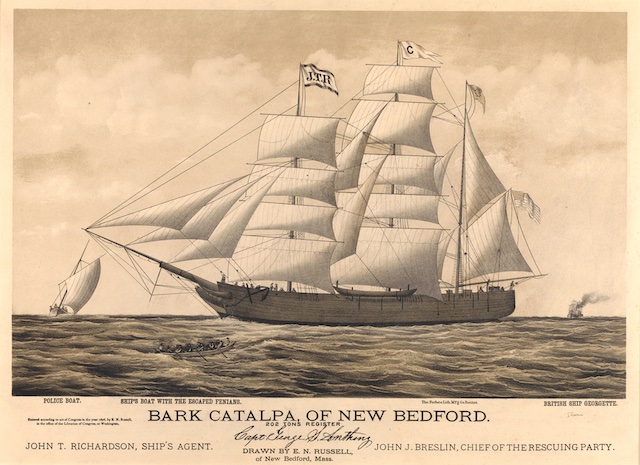

But John Boyle O’Reilly did not forget. Now, editor of The Pilot in Boston, he plotted a rescue with a small band of Irish-Americans. If it was difficult to bribe a captain to hide one man on a whaling ship, the solution was to buy a whaler, sail to Western Australia, pick up the prisoners, and sail it home again to America.

(Circa 1897).

The simple plan took months and months of planning. The small band of conspirators raised money, purchased a vessel, and set it up for whaling. To command the enterprise, they hired a 28-year-old New Bedford sea captain, George Anthony, who had absolutely no reason to agree to this reckless adventure. Anthony was not Irish, he was the father of a newborn daughter, and he had just promised his wife he would never go to sea again. But he was a Yankee sea captain, whose life was ruled by a love of adventure, the call of the sea, and a passion for liberty.

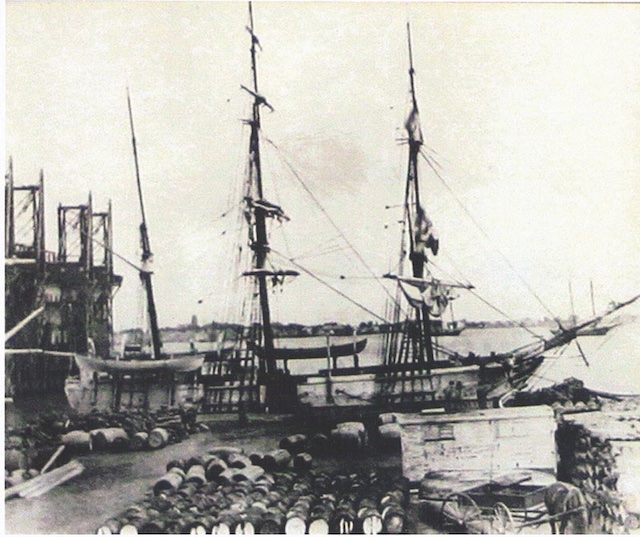

The ship Catalpa sailed on April 29, 1875. Its crew of Malays, Sandwich, and Cape Verde islanders had signed on for a two-year voyage in search of whales. Their hopes for a successful hunt were raised when they killed their first whale after seven days out and when they had sent back 200 barrels of oil (worth $12,000) to New Bedford by the end of October.

However, when they crossed the equator, the crew members were aware they were leaving the best whaling grounds and became increasingly restless and difficult to manage. It was only at this point that Captain Anthony confided the true nature of the voyage to First Mate Samuel Smith. The two men agreed to push on – they were expected in Western Australia by January and it was already November.

Meanwhile, John Breslin and Thomas Desmond sailed from Los Angeles for Western Australia to set up a land-based operation in Fremantle to arrange the breakout from the prison and subsequent transportation to the ship. By November, Breslin was set up in Fremantle and Desmond in Perth and soon afterward, their plans were operational. They and the prisoners anxiously awaited Catalpa.

Day after day, week after week, there was no word. Finally, on March 26, 1876, Catalpa arrived in Bunbury, Western Australia’s whaling port, 70 miles south of Fremantle. Breslin outlined the plan to Captain Anthony. Catalpa was to stand 10 to 12 miles offshore, well out in international waters, and send a whaleboat to Rockingham Beach. The prisoners were to break away from their working parties and, in rented horse carriages driven by Breslin and Desmond, make the 20-mile dash from Fremantle to Rockingham.

That escape was set for April 15, the Saturday before Easter. However, on Friday, a heavy storm blew, dragging the ship’s anchors and she was unfit to sail in the morning. The operation was postponed until Easter Monday.

Breslin and Desmond had worked out the details of the plan with precision – even down to which horses were to be rented for the escape. Sunday night, the local hosteler told them the horses he had promised for Saturday were already committed to someone else on Monday. At first, the conspirators were crushed by the news, but they took heart when they learned the reason why the horses would not be available.

The annual regatta of the Perth Yacht and Boat Club, now known as the Royal Perth Yacht Club, was to be held on Monday, and the best horses in Fremantle had been previously assigned to local officials for the journey to the regatta. Breslin and Desmond could not expect speedy horse flesh for the race to Rockingham, but they had the consolation of knowing that local government officials would not be in the race at all.

The word that the escape had been changed to Monday was passed to the prisoners by a trusted parolee. That morning, the six military prisoners were assigned to work details outside the prison walls. By 8 a.m. they had slipped away and made their way to Rockingham Road. Breslin and Desmond were waiting. Three prisoners jumped into each coach and they flew off in a mad dash for Rockingham beach and freedom.

The exhausted, perspiring horses, near collapse at the end of the two-hour and 20-minute gallop, were quickly abandoned by the conspirators who rushed to the water’s edge where Anthony and his crew were waiting to spirit them away. All too soon to learn that the waters of the Indian Ocean were as formidable a jailer as had been the land of Western Australia.

After two hours of steady rowing, the whaleboat cleared the harbor and the crew hoisted sail and steered in a southerly direction in search of Catalpa. Five hours later one of the crew spotted the vessel but it was at least 15 miles away and the night was rapidly approaching. They rowed and sailed until 10 p.m.

A sudden fierce wind snapped the mast and the best they could do was to hoist the jib on an oar and steer a course that was their best estimate of the direction of Catalpa.

Throughout the night, rough seas threatened to swamp the overloaded whaleboat, but all hands kept their faith in their goal and their backs to the oars. At 7 a.m they again spotted the sails of Catalpa and bent to the oars with renewed vigor. By early afternoon they saw the ship turn and head straight for them. They had been sighted. They would soon be safe and free.

Just as they began to relax, one of the crew spotted another sail! It, too, was headed straight for Catalpa and was about the same distance from the large ship on the landward side as they were to seaward. It was the Water Police Cutter – trying to head them off. Captain Anthony urged his crew of South Sea islanders on as if they were closing in on a prize sperm whale. The crew strained every muscle until each fiber was numbed beyond pain. The prisoners and Breslin and Desmond clung to the gunwales, tense with fear and paralyzed by their inability to help.

Aboard Catalpa, First Mate Smith worked the ship between the onrushing boats. Closer and closer he edged towards Captain Anthony, enabling the whaleboat to win the race – with only minutes to spare. The police boat was soon alongside but its Captain did not contest the race. Out of admiration for the daring escape, and in the tradition of Australian sportsmanship, he gallantly saluted the winner, “Goodbye Captain, goodbye!”

The victors had spent 28 hours in an open whaleboat on ugly seas in a race against death. They could celebrate only by changing their clothes, eating a warm meal, and immediately going to sleep.

Back on shore, popular sentiment sided with the prisoners – but not everyone was ready to concede. The Governor of Western Australia was furious. Together with the Colonial Secretary, the Prison Warden, and the Superintendent of the Water Police, they decided to commission and arm the coastal steamer, Georgette, and send her in pursuit.

As Wednesday dawned, a lookout on Catalpa shouted that a steamship was closing in on them rapidly. By 6 a.m. all hands could see Georgette flying the British Man-of-War and the Vice Admiral’s flags, armed with guns, a company of artillerymen and Water Police on deck. The Irish prisoners saw that the governor was determined to recapture them. They lay below with rifles and revolvers ready, all determined to die rather than be put back in chains.

Georgette fired a shot across the bow of Catalpa. Captain Stone of the Water Police shouted “Heave to.” Anthony refused. Stone returned. “If you don’t heave to, I’ll blow the masts out of you.”

Captain George Anthony of New Bedford, who a year earlier was working for New Bedford House Twist Drill Company, enjoying his young wife and newborn daughter, and who now found himself half a world away, in danger of death or life imprisonment, ran up the Stars and Stripes and shouted, “That’s the American flag. I am on the high seas. My flag protects me. If you fire on this ship, you fire on the American flag.“

Georgette had no response. Anthony’s remark had shattered the confidence of the government men. Still, the Georgette shadowed them. Finally Captain Stone called out, “Won’t you surrender to our government?”

To this weak request Anthony did not even reply. Georgette hailed again. “Can I come on board?” Captain Anthony answered. “No sir. I am bound for sea and can’t stop.”

The game was over. Georgette turned back to Fremantle. Catalpa sailed on. To America. To freedom. The stars and stripes had won the day. ♣

Inscribed on the monument are the names:

Martin Hogan (1833–1901), Thomas Hassett (1841–1893),

James Wilson (1836–1921), Michael Harrington (1825–1886)

Thomas Darragh (1834–1912), Robert Cranston (1842–1914)

John Boyle O’Reilly (1844–1890).

Memorial Markers

The Fenian Memorial Committee of America founded and spearheaded by George McLaughlin is dedicated to marking the graves of the Fenian dead. In October 2022, the organization completed its mission to ensure that the Catalpa Six were commemorated and their gravesites marked appropriately. The final two, Michael Harrington and Thomas Hassett, both from County Cork, whose graves had previously been unmarked, were provided with commemorative stones at Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York. Most recently, on Saturday April 2026, 2025, John Goff, the main fundraiser of the Catalpa Rescue mission was honored.

The Fenian Memorial Committee of America founded and spearheaded by George McLaughlin is dedicated to marking the graves of the Fenian dead. In October 2022, the organization completed its mission to ensure that the Catalpa Six were commemorated and their gravesites marked appropriately. The final two, Michael Harrington and Thomas Hassett, both from County Cork, whose graves had previously been unmarked, were provided with commemorative stones at Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York. Most recently, on Saturday April 2026, 2025, John Goff, the main fundraiser of the Catalpa Rescue mission was honored.

Editor’s Note: This article ran in the October 1987 issue of Irish America with the tagline “As recalled by Donald J. McGilligan.” ©The Pilot.

Why is the captain not named on the monument in Australia

Along with my late American wife who had no Irish connections, We visited just about all the places mentioned about Western Australia. Eventually, after travelling around the country we flew from Melbourne to Tasmania. The article is extremely interesting. It would also be of note to hear about other famous Irish such as John Mitchell who escaped from Tasmania. The son of a Presbyterian minister from Derry who dresssed as a priest during part of his escape from Tasmania and later became well known in New York. Also, there is the famous escape of Thomas Francis Meagher who later became acting Governor of the Montana Territory. (Territory of the Mountains) Meagher later drowned in a famous river.