Joe Biden’s nail-biting Pennsylvania win was just the latest episode in Pennsylvania’s rich Irish American history.

You can take the boy out of Scranton. But Scranton still helped put its most famous Irish Catholic boy – Joe Biden – into the White House.

The 2020 presidential election famously came down to a handful of states – including Pennsylvania. That’s where Joseph Robinette Biden was born, in St. Mary’s Hospital, to Joe Biden Sr. and the former Jean Finnegan, before the family moved to Delaware.

In 2016, Donald Trump won Pennsylvania’s 20 electoral votes by a razor-thin margin, propelling him to the White House. Four years later, Biden was able to win his home county of Lackawanna by an estimated 10,000 votes – a big help in securing his own slim margin of victory in the Keystone state, and pushing the former VP over the top and into the White House, as just the second Catholic U.S. president.

“One of the reasons Joe Biden won this race was labor,” Allegheny County executive and Irish American power broker Rick Fitzgerald told MSNBC after the election. “[Biden] got a lot of votes in the building trades. They voted for Joe Biden in much, much bigger numbers than they did for Hillary Clinton, when I talk to my friends like Tommy McIntyre at the Electricians (union)…. Joe Biden being a labor guy, labor is the thing that that carried him over in southwestern Pennsylvania.”

IRISH POWER BROKERS

The Irish remain bi-partisan power brokers in Pennsylvania. The state is represented in the U.S. Senate by Republican Patrick Joseph Toomey and second-generation Democratic senator Bob Casey Jr.

Pennsylvania Congressional reps include Republicans such as Brian Fitzpatrick and Mike Kelly. In recent years, however, Democrats have been energized by younger Irish-Americans such as Congressional reps Conor Lamb, and Brendan Boyle, the 43 year-old son of Irish immigrants, whose brother, Kevin, is a state rep.

Philadelphia mayor Jim Kenney also speaks often of how his Irish heritage and south Philly upbringing informs his policies for the city of brotherly love.

Biden’s nail-biting Pennsylvania win was just the latest episode in Pennsylvania’s rich Irish American history – from Grace Kelly and Gene Kelly to the Molly Maguires and an unforgettable Bobby Kennedy speech.

A HOLY EXPERIMENT

William Penn envisioned the future state of Pennsylvania as a “Holy Experiment.” Penn’s Quakers were persecuted in England so the colony’s founders made efforts to reach out to minorities, including Catholics and Native Americans. Though its founders were heavily Quaker, Irish immigration to Pennsylvania during the 1700s was largely Presbyterian and Scotch Irish. In 1776, the Declaration of Independence may have been conceived and written by Franklin, Adams and Jefferson, but it was printed by a local Irish immigrant from Tyrone named John Dunlap.

By then, Philly’s Irish community was so strong it formed The Friendly Sons of St. Patrick on St. Patrick’s Day in 1771. It was made up of prominent merchants and military men, such as Commodore John Barry and Cork native Stephen Moylan, a close aide to Washington who later became the Friendly Sons’ first president. From the start, the Friendly Sons was made up of both Catholics and Protestants. This certainly fit William Penn’s original harmonious vision. After all, Pennsylvania was one of the few colonies that did not ban Catholic religious services.

Away from the intellectual fervor of Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Irish were forging more modest lives. Consider County Donegal immigrant James Crockett and his wife Hannah. They purchased over 100 acres of land in western Pennsylvania, after Crockett struggled for nearly 20 years as a Philadelphia stonemason. In an 1822 letter to his father in Ireland, Crockett wrote:

“It is killing on nature to work outdoors in this country, the summers are so hot and the winters so cold, but I now have 30 acres cleared, 20 cattle, and a good harvest. We are happy and contented. Our house is small but our barn is full. Thank God I came to this country where we are free from landlords, rent and the fear of eviction.”

THE CANALS AND THE RIOTS

As was the case throughout the U.S., more and more Irish Catholics came to Pennsylvania during the first decades of the 1800s. Once arrived, there was hard work to be done. The Pennsylvania Canal from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh was completed in the 1830s. Naturally, with this hard work came demands for better conditions. Three hundred Philadelphia coal heavers, in 1835, went on strike and called for a 10-hour day.

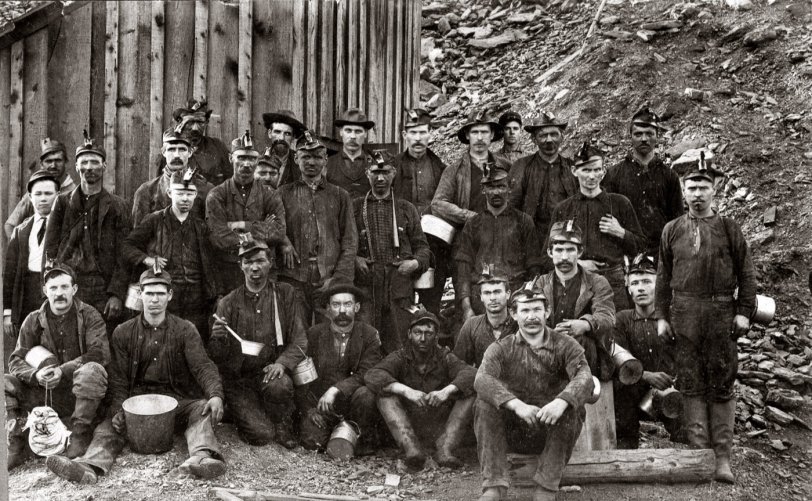

The Irish of Pennsylvania would spend the first half of the 19th century digging canals, and the second half digging in the mines.

Meanwhile, by the 1840s, William Penn’s vision of tolerance was about to face its toughest test. In 1844, a number of Irish homes, two Catholic churches and a Sisters of Mercy seminary were all burned to the ground by nativist mobs. The Irish responded by violently disrupting a meeting held by the anti-immigrant American Party. The Philadelphia Riots illustrated the wave of anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment spreading across the U.S. at the height of the Famine. At the same time, the Pennsylvania Irish were advancing. Just a year before the riots, in September 1843, Father John Possidius O’Dwyer was named president of a new Augustinian University in Philadelphia. Villanova, as the school was called, would go on to educate generations of Pennsylvania’s Irish Catholics.

THE MOLLY MAGUIRES

By the 1870s, one of the most notorious labor episodes in U.S. history unfolded in Pennsylvania’s coal region, when Irish miners formed a union to counter harsh policies of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad. A faction within the union, calling itself the Molly Maguires, often used intimidation and even violence to pressure management. Twenty alleged Mollys were ultimately hanged in 1877, based on what is now believed to be flimsy evidence.

A more moderate figure in the Pennsylvania labor movement was Terence V. Powderly, one of 12 children born to Irish immigrants who settled in Carbondale. Powderly later became affiliated with a secret labor group that came to be known as The Knights of Labor, the most influential union of the late 19th century. Again, in keeping with William Penn’s vision, the Knights reached out to African Americans as well as women, such as Irish immigrant Leonora Barry, who led a key Knights committee.

THE 20TH CENTURY

As the Pennsylvania Irish assimilated, they left the canals and the mines, and dynamic artists emerged. Gene Kelly (born 1912) and Grace Kelly (born 1929) hailed from Pennsylvania’s cities, while famed novelist John O’Hara was born in Pottsville in 1905.

One character in O’Hara’s best-seller Butterfield 8 summed up the author’s sense of Irishness:

“I want to tell you something about myself that will help to explain a lot of things about me. You might as well hear it now. First of all, I am a Mick. I wear Brooks [Brothers] clothes and I don’t eat salad with a spoon and I probably could play five-goal polo in two years, but I am a Mick. Still a Mick.”

Irish political and church leaders left their

mark on the state as well. The “father of the

Pittsburgh Renaissance,” David Lawrence, was mayor of the Steel City from 1946 to 1959. Before Lawrence’s election, Pittsburgh was a smog-choked city regularly beset by floods. Lawrence not only cleaned up the city’s streets and air, he brought Pittsburgh’s moribund economy into the 20th century. Lawrence, according to one survey of great American mayors, loved to tell “Irish and Catholic stories as if he were straight off the boat from County Mayo.”

Philadelphia did not elect an Irish Catholic mayor until James H.J. Tate in 1962. But Archbishop Dennis Dougherty (the son of an immigrant coal miner) was a powerhouse in his native city for decades, before dying in 1951.

President Biden’s maternal great-grandfather Edward Francis Blewitt, the son of Irish immigrants, was a founding member of the Scranton / Lackawanna County, branch of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick in Lackawanna County. In March of 1964 – just four months after JFK’s assassination – Bobby Kennedy, in first public speech since his brother was killed, addressed the Friendly Sons. In was an emotional speech, he urged that those present to recall the heritage of the Irish. “Let us hold out our hands to those who struggle for freedom today – at home and abroad – as Ireland struggled for a thousand years. Let us not leave them to be ‘sheep without a shepherd when the snow shuts out the sky.’ Let us show them that we have not forgotten the constancy and the faith and the hope – of the Irish.”

Senator Biden spoke on St. Patrick’s Day in 1973, just a couple of months after his wife Neilia and his 13 month-old daughter were killed in a car crash, just before Christmas 1972. Putting aside his own grief, like Kennedy, he urged the Irish to think of others, in a way that says much about the empathetic president he will make: “The Irish should acknowledge the cries of others for liberty, because if we short-change those “others” in America, we are really short-changing America.” ♣

Leave a Reply