By Tom Deignan

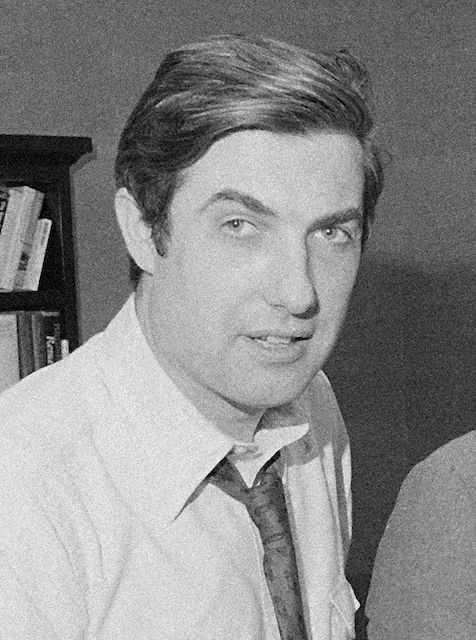

His name was Cornelius Mahoney Sheehan. A son of Irish immigrants, he was born at the height of the Great Depression and raised on a farm in Massachusetts.

By the time “Neil” Sheehan died earlier this month, at the age of 84, he’d won an armful of literary awards, and played a key role in altering the course of U.S. history, as depicted in Hollywood films like 2017’s Oscar-nominated The Post, featuring Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep, as well as Justin Swain, as Sheehan himself.

“The Pentagon Papers, arguably the greatest journalistic catch of a generation, were a secret history of United States decision-making on Vietnam,” the New York Times noted earlier this month.

“Their release revealed for the first time the extent to which successive White House administrations had intensified American involvement in the war while hiding their own doubts about the chances of success.”

How Sheehan came to get his hands on the Pentagon Papers is not only (as the Times put it) “a tale as suspenseful and cinematic as anyone in Hollywood might concoct.”

It also had a distinctly Irish American conflict at its center.

This international thriller begins humbly enough on a dairy farm outside of Holyoke, where Sheehan and his two brothers grew up attending mass every Sunday, at the insistence of their immigrant mother, Mary O’Shea.

An outstanding student, Sheehan received full scholarships to a private high school, then Harvard.

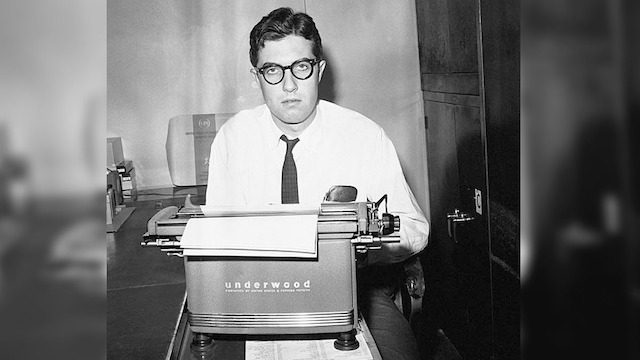

Afterwards, he went off to Asia, first serving in the U.S. Army, then as a journalist for United Press International (UPI).

By then, the country Sheehan grew up in had moved from depression and poverty to affluence and power.

The United States sought to exert this newfound might across the globe – in Europe, then Korea, then Vietnam, often in the name of fighting Communism.

By 1966, Sheehan – now reporting for UPI from Saigon – had grave worries about the expanding anti-communist war in southeast Asia.

“I simply cannot help worrying that, in the process of waging this war, we are corrupting ourselves,” Sheehan wrote for The New York Times in 1966.

“I wonder, when I look at the bombed-out peasant hamlets, the orphans begging and stealing on the streets of Saigon and the women and children with napalm burns lying on the hospital cots, whether the United States or any nation has the right to inflict this suffering and degradation on another people for its own ends.”

What then followed was a tragedy featuring two aspects of the Irish immigrant experience.

On one side was Sheehan, skeptical of a powerful nation meddling in the affairs of a smaller one – as the British had done to the Irish for centuries.

On the other side was a former JFK adviser who, by 1966, was serving as Secretary of Defense under President Lyndon Johnson.

Like Sheehan, Robert McNamara had also gone to Harvard, then into the military.

But coming of age a generation earlier, McNamara’s ambitions were to join the American elite that had excluded Irish Catholics for so long.

As depicted in The Post, a U.S. State Department analyst named Daniel Ellsberg went to Vietnam to track the war’s progress for McNamara, who was becoming increasingly worried that the war was not winnable. McNamara, though, did not reveal these concerns to the public.

Ellsberg later made copies of thousands of documents which chronicled America’s years of misguided involvement in Asia. He then leaked these documents to an ambitious reporter from The New York Times – Neil Sheehan.

What ensues are not just explosive diplomatic and military revelations, but a fight over whether or not the Times – and later Washington Post – can legally publish these “top secret” documents.

The so-called “Pentagon Papers” have since become a symbol of the public’s right to know about government actions.

But Sheehan’s journey into the depths of Vietnam was just beginning.

After attending the funeral of John Paul Vann, “a charismatic, idealistic former Army officer and outspoken dissenter on the war,” as the Times put it, Sheehan planned to “write the history of the war through the figure of Mr. Vann, who seemed to … embody the qualities that Americans admired in themselves, and to personify the American venture.”

Sheehan expected to complete the book in a few years. Instead, it took nearly two decades.

A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam was finally released in 1989, winning a National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize.

Reviewing it in the Times, Ronald Steel wrote, “If there is one book that captures the Vietnam War in the sheer Homeric scale of its passion and folly, this book is it.”

In our digital age, a story of secretly photocopying pages and pages of paper might seem like ancient history.

But as illustrated by the ongoing saga of Wikileaks and Julian Assange – in the news just this week, after Assange was passed over for a pardon by former president Donald Trump – Sheehan’s fight for what the public should know about government action is as timely as ever.

Tom Deignan is an author, teacher, and columnist for the Irish Voice and Irish America (tdeignan.blogspot.com).

Leave a Reply