By Margy Kinmonth

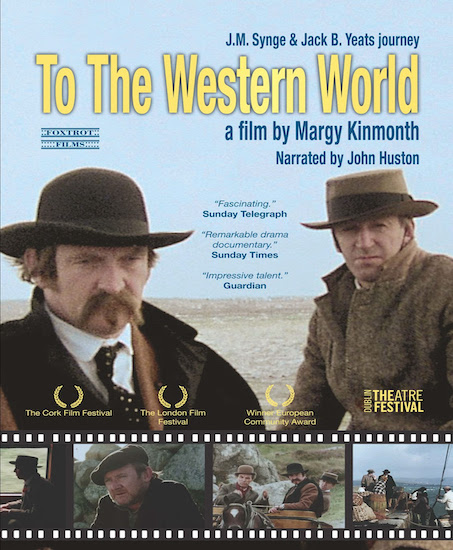

Filmmaker Margy Kinmonth writes about making To The Western World, a film inspired by the paintings of Jack B. Yeats, and how she enticed film director, screenwriter, and actor, John Huston to narrate the film.

Get information on the film here and listen to talk-back panel discussion free.

One of the first films I directed was driven by my passion for Jack B. Yeats –Ireland’s greatest painter. I wanted to make a film about Yeats using the finest ingredients – stormy landscapes, his visionary colour palette, deft brushstrokes, and his people, in a word the unique vision Yeats created of his country – Ireland.

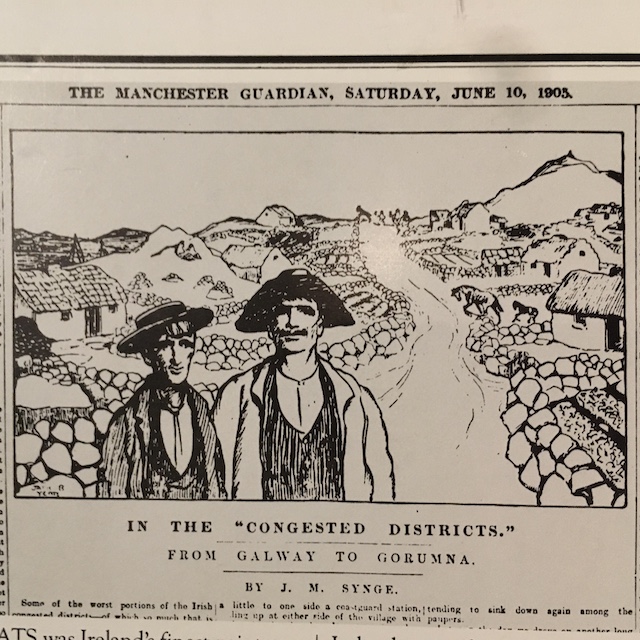

My story was based on a remarkable discovery I’d made – a series of articles on microfilm, lurking unseen in an archive of the Manchester Guardian, dated July 1905. My screenplay was based on the travels of the Irish playwright John Millington Synge and Jack B. Yeats the painter, on a commissioned journey across the West of Ireland, to the Gaeltacht areas known as the Congested Districts – the barren, poverty-stricken over-crowded coastal regions. They walked all across Connemara and Mayo, meeting the people, drawing and reporting as they went, where post famine “piece work” – stone-breaking, building roads, bridges and piers, or kelp collecting, was the only alternative to emigration to America, or else starvation.

I knew this journey would be a compelling subject for a film. I’d personally experienced the romantic wildness of the remote islands of the West of Ireland while sailing with my father – a surgeon born in Lisdoonvarna, County Clare; he had the sea in his blood and taught me to understand the power of the ocean. As children, we ploughed the stormy waters up and down the coast and I used to draw and paint pictures from the cockpit, including the currach races off Inishmaan.

I was determined to make this film, shooting entirely on location in the real places, despite the constant rain and wind featured in the artist’s work. For my research I visited the painter Anne Yeats, daughter of the poet W. B. Yeats, who gave me her blessing to make the film and use her uncle’s sketchbooks. She lived outside Dublin, and when I arrived, she was busy painting a still life of eggshells on the kitchen table, so for lunch we had a vast mountain of scrambled egg. Yeats drew from what he called his “memory pool” and as I searched through the sketchbooks, preserved in tissue paper, I found many unpublished drawings from the trip, including a watercolour of John Millington Synge lying in a tree, which would become a scene in the movie.

I had some stories over whisky with Yeats’s dealer Victor Waddington, who told me that Yeats believed his painting rags contained visionary powers and used to burn them after each day’s work. He gave me some covers from the actual sketchbooks to use as props.

I cast Abbey actors with performers of the Druid Theatre company in Galway along with non actors in the West of Ireland. The film starred Tom Hickey as Jack Yeats and Patrick Laffan as John Millington Synge, with comedian Niall Toibin playing the ferryman. It was shot entirely on location, on Gorumna Island in Connemara. The actors’ dialogue was the never-before performed words of playwright John Millington Synge (“Playboy of the Western World” and “Riders to the Sea”) who transcribed exactly what he overheard in the cottages.

Clockwise: Director Margy Kinmonth, actor Niall Tiobin as the Ferryman, actor Tom Hickey filming on the pier built by relief work at Letternore Connemara. Filming the pony cart with the director of photography Ivan Strasburg and director Margy Kinmonth and Lucy Ferry. John Huston is pictured below.

My other great hero was the Hollywood film director John Huston, famed veteran of dozens of movies including “Maltese Falcon,” “Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” “Key Largo,” but less well known for his love of Ireland, where he lived for 15 years with one of his five wives and raised some of his children including Tony and Angelica Huston. I wanted John Huston to narrate my film, to be the voice of God. How was I going to achieve this?

My other great hero was the Hollywood film director John Huston, famed veteran of dozens of movies including “Maltese Falcon,” “Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” “Key Largo,” but less well known for his love of Ireland, where he lived for 15 years with one of his five wives and raised some of his children including Tony and Angelica Huston. I wanted John Huston to narrate my film, to be the voice of God. How was I going to achieve this?

The film which I’d written, directed, and produced on passion and fresh air, aided by crews, cooks, and cabbies, did not have a budget for Hollywood A-listers like Huston. But I did know he loved Ireland, so when I heard he was due in London for the book launch of his autobiography “An Open Book” I sprang into action. I called up his legendary agent Paul Kohner in Sunset Boulevard – his secretary Irene Heyman, in the shower at the time, she said she’d pass on my message but stressed that Huston’s schedule was extremely tight and health issues made him unable to consider work, so he’d be largely confined to the Savoy while in London, with the odd trip across the river to the British Film Institute. He might just be interested in meeting but no voiceovers.

At the time, inspired by film director Ridley Scott, I was working as a young commercials producer and director in advertising, the world of “Mad Men,” which was the done thing for film directors then – we were making mini-feature films. I’d been out to lunch, it was the era before cell phones and I got back to find a tiny handwritten note scribbled on the blotter on my desk, written upside down in hasty writing by someone who just happened to be passing. It said “Huston, 11.15, Savoy Hotel tomorrow” There was no more information and I never found out who took the message. Tomorrow!

I hastily assembled a producer friend, who owned a Nagra sound recorder. I managed to get hold of Huston’s autobiography, not yet in the shops, and speed-read the entire book, a great yarn packed with movie anecdotes of his long life, which further fuelled my mission. I discovered that Huston had made a swap with another Hollywood director Otto Preminger who wanted him to play a role in his movie; as there was no money Preminger gave Huston two paintings by Jack B Yeats in lieu of a fee. As I also had no money, I decided that if Huston did agree to give me his voice for my movie, that I would give him my precious copy of “Life in the West of Ireland” a rare illustrated limited edition by Jack B. Yeats, in exchange for his voice of God.

So I was going to meet the man in the morning! In anticipation of things going my way I spent the night writing and rewriting the voiceover script to the cutting copy, with remote help from my inspirational business partner and historian, Nick Murray, with whom I’d set up my own production company Foxtrot Films. We finished the script, timed it, tried it out and typed up a carbon copy for the voice.

It was dawn. I’d booked a studio in Covent Garden in case I could persuade Huston to record to picture. I was also meant to be recording the voiceover for a Boots commercial that morning, with John Le Mesurier of “Dad’s Army.” So I postponed that and set off to the Savoy instead.

I met my sound recordist in the grand marble lobby and asked him to act like a casual friend tagging along and not behave like a typical crew member. I asked the concierge to help me keep the room silent by not putting phone calls through and also turning off the noisy air conditioning – all fine. I went into his suite of luxury deep pile carpets and found John Huston settled in an armchair, wearing velvet slippers with gold foxhounds embossed on the toes. He seemed so familiar that I almost expected to find Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in there too. When he stood up, it was like watching an ironing board unfold as he reached his full height of well over six foot and leaned over to shake my hand – with his deep bass voice and large welcoming hands he could not have been more charming.

He wanted to talk about Ireland, was it all just the same? He wanted news of the magic and the fairy rings, the banshees, and the resident ghost, he wanted to remember the wonderful Irish people who were his neighbours. He told me a story of when he was in London in 1943 during the Blitz, during rationing, including unrepeatable detail of how he got caught short in the blackout near the Dorchester in an air raid. He told me how he discovered the world of painting, and became fascinated by pigments and canvasses, and Jack B. Yeats. He asked me all about my film.

So I put the script in front of him and he began to read, and we began to record, and his words in his deep bass voice rolled out like poetry, reviving the spirit of Synge and Yeats and their unique journey, immortalizing the people long gone who lived there and survived the famine or emigrated to the cities. And it was done.

So I put the script in front of him and he began to read, and we began to record, and his words in his deep bass voice rolled out like poetry, reviving the spirit of Synge and Yeats and their unique journey, immortalizing the people long gone who lived there and survived the famine or emigrated to the cities. And it was done.

But there was still some business, with my producer’s hat on, I confessed I was sorry I had no money, but I’d still need a release form, so I offered him the contract with one hand and my gift with the other… there was no hesitation as he signed, saying “I’ll do it for Jack Yeats… and for Ireland”

The New York Irish Center presents the virtual premiere of To The Western World. Get information on the film here and listen to talk-back panel discussion free.

Following the online screening, there will be a talk-back panel hosted by Turlough McConnell with filmmaker Margy Kinmonth and guests Professor Christine Kinealy, founder of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University, and Cormac O’Malley, an important collector of Irish art and historian, whose father, the Irish rebel leader Ernie O’Malley, was a close friend of Jack B. Yeats and had several of Yeats’s sketchbooks.

The broadcast and panel discussion is a special feature

of the 2021 Origin 1st Irish Virtual Theatre Festival.

Get information on the film here and listen to talk-back panel discussion free.

“TO THE WESTERN WORLD” a Margy Kinmonth film, premiered at the London Film Festival, won the European Community Award and was nominated for the Cork Film Festival Fiction Award. It was shown at the Dublin Theatre Festival and on Channel4 Television, and every year on St Patrick’s Day it is shown on RTE.

“To the Western World” is also available on DVD at store.foxtrotfilms.com.

Leave a Reply