By Tom Deignan

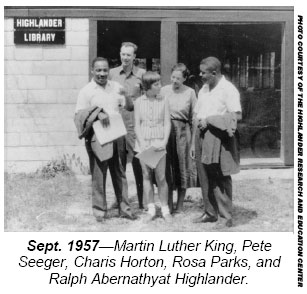

In 1957, Martin Luther King. Jr. paid a visit to a Tennessee community organizing camp where he heard Pete Seeger perform a revised version of an old gospel tune for the first time.

Within a decade, “We Shall Overcome” would become an anthem for civil rights marchers from Birmingham to Belfast.

Martin Luther King Day in the U.S. is a fitting time for the Irish on both sides of the Atlantic to recall that music has always played a central role in the struggle for social justice. From rebel tunes to protest folk, haunting airs to righteous hip hop anthems, music often moves people – sometimes literally – in ways that speeches or essays simply cannot.

And we are still learning about the key contributions Irish artists made in struggles for equality that began in the 20th Century and continue today.

A new book, for example, sheds important light on a once-popular, largely-forgotten County Down singer named Ottilie Patterson.

In How Belfast Got the Blues, authors Joanna Braniff and Noel McLaughlin argue that Patterson – who toured the U.S. and U.K. with some of the top blues artists of the 1950s and 1960s – profoundly influenced up-and-coming rockers like Mick Jagger and Eric Clapton.

These British bad boys are often credited with connecting European and Black American music styles, and challenging old traditions – in music, then on political matters.

But it was Ottilie Patterson – a proudly-Irish female singer, who shared stages with top Black artists like Big Mama Thornton and Sister Rosetta Tharpe – who paved the way, Braniff and McLaughlin argue.

Patterson “can legitimately claim a veritable host of previously unacknowledged firsts that exceed her role in inspiring, and fostering, 1960s English R&B bands and groups such as the Rolling Stones and The Pretty Things,” the authors write.

This broader story of Ottilie Patterson, Irish blues, and trans-Atlantic civil rights goes on to include Elvis and the Beatles, Frank Sinatra and John F. Kennedy, Van Morrison, and a generation of Unionist politicians who wanted to promote Northern Ireland’s music scene but became nervous when people like Patterson started to challenge systemic bigotry.

“She was making the direct connection with Civil Rights that was happening in America. She was breaking the color bar,” Braniff said on a recent podcast “New Books in History.”

Patterson toured the U.S. with black artists at a time when strict racial segregation was still the law. She went on to help form a group called Stars Campaign for Interracial Friendship (SCIF) – decades before more famous coalitions like Rock Against Racism – which challenged bigotry on both sides of the Atlantic.

Patterson was “using blues music in a subtle political way. And sometimes not so subtle political way. And that became dangerous…for the Northern Ireland government,” said Braniff. “To have somebody from Northern Ireland at the forefront in (the U.S.), where the struggle for Civil Rights was starting to happen. The same thing was being mirrored in her hometown. She had the potential to open the dialogue at the time when the Unionist government really didn’t want those parallels to what was happening in the States to be explicit.”

In the wake of Patterson’s activism, many other pop stars became more political. Frank Sinatra campaigned for John F. Kennedy, who – once elected president in 1960 – opened up Washington’s political scene to a wide range of artists, including Ottilie Patterson.

She received “critical accolades on her final American tour … when, in the summer of 1962, she sang at President John F. Kennedy’ s International Jazz Festival in Washington, sharing the bill with Duke Ellington, Dave Brubeck and Gerry Mulligan,” McLaughlin and Braniff write.

When Patterson died in 2011, Hot Press magazine recalled that the response to Patterson’s performance “was so overwhelming Duke Ellington’s arrival on stage was delayed for ten minutes. It’s said someone shouted out from the largely African-American audience, ‘How you sing like us, girl?’”

How Belfast Got the Blues adds: “When the most popularly progressive, and first Irish-Catholic, US president of the twentieth century invites an artist such as Patterson to sing, one gets a sense of the power of music, even in a general sense, to shape political opinion.”

Acts like The Beatles and Rolling Stones also went onto become more vocal on social issues – including Ireland. The Beatles backed Labor politician Harold Wilson, and their 1964 film Hard Day’s Night included a performance by Irish actor Wilfrid Brambell as Paul McCartney’s Irish Republican grandfather.

The Rolling Stones, meanwhile, shot an early concert film in Belfast which plays a central role in How Belfast Got the Blues. Called Charlie is my Darling: Ireland 1965, the film features a title sequence with a map of Ireland – but no border between the north and south.

By the late 1960s, Ottilie Patterson slowed her performance schedule, after years of touring. But she was still at the forefront of social issues. In 1969, she and a group of other artists (including Charlie is my Darling director Peter Whitehead) sent a letter to the Belfast Telegraph urging Northern Ireland’s divided communities to band together – as Irish Catholics and Protestants had done in the past.

“In April 1969, Patterson joined Whitehead and the Stones in mobilizing the United Irishmen to progressive political ends, sending a telegram to the Belfast Telegraph,” McLaughlin and Braniff write. This message “urged the people of Belfast to ‘catch themselves on’ and, significantly, that ‘Henry Joy McCracken would be turning in his grave’.”

In a day and age where many artists are celebrated for such activism, it may be hard to understand why Patterson’s role has gone underappreciated for so long.

But Braniff observes: “There is a tradition unfortunately in Northern Ireland of women’s voices being suppressed. Ottilie – despite her amazing talent, despite her vision, despite her commitment – has kind of fallen victim to that.”

Tom Deignan is an author, teacher, and columnist for the Irish Voice and Irish America (tdeignan.blogspot.com).

Wow!! TY!! Ottilie Patterson is Amazing!! It is a wonderful reminder of the historical ties between African Americans & the Irish beginning with Frederick Douglass’s travels to Ireland and the warm reception he received. In his own words, as a fugitive slave, “the 1st time I felt free”.

Ottilie Patterson, inspired by and welcomed into the Blues community, highlights the significance of music to both cultures as an essential form of communication in friendship and in strife.

While I am a Progressive, per the North’s misogyny & diminishing the efforts of women, I have to quote Peggy Noonan of the WSJ 01/15/21 on Liz Cheney, “What Leadership Looks Like”. (The GOP) is “dumb, male & clubby.. and she (Liz) needs to be suppressed”.

What a better world we would have if the Voices of so many, like Ottilie Patterson, had not been brushed to the side.

Sláinte

My general impression of Irish Americans is that they have been historically the most racist ethnic group in America, so I am thrilled to read stories like yours which depict native Irish as quite the opposite.