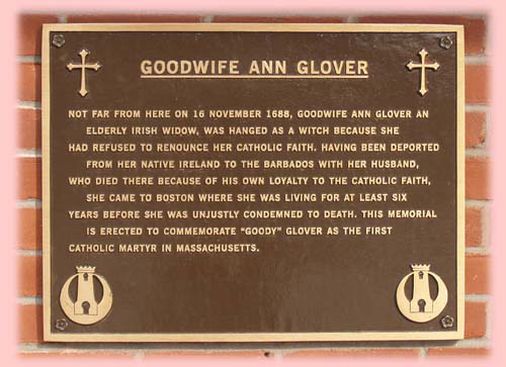

Goody Ann Glover was hanged as a witch on November 16, 1688. Could it have been that it was because she was a Catholic whose first language was Irish?

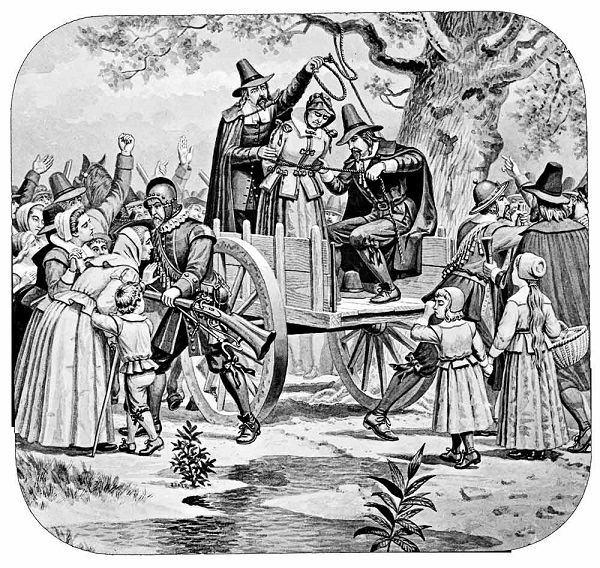

Had one not known the dour Puritans of this New England town better, one might have thought they were celebrating a holiday but, in fact, they had come out to witness the hanging of a witch. From jail to the gallows they followed the convicted wretch, a tired, crazy old woman, heaping abuse, mockery, and rage upon her.

Belief in witchcraft was universal in the Old World, and the first colonists carried it to America. Even the tolerant William Penn served as judge in a Pennsylvania witchcraft case, but what was unusual in this case was that the accused witch was not a Puritan, but an outsider – an Irish Catholic named Goody Glover.

We do not know which part of Ireland Goody Glover came from, only that she and her husband were sold into slavery and transported to Barbados during the reign of Oliver Cromwell. Around 1680, by this time widowed, she arrived in Massachusetts with a daughter, Mary, in tow – part of a clutch of servants and Indian slaves brought to the colony from Barbados. (Several of this group were bought by the Reverend Samuel Parris, the minister who “discovered” the first Salem witches in his household.)

Although no specific incident has been recorded, Goody Glover evidently acquired the reputation of “an ignorant and a scandalous old woman,” in the words of the unsympathetic Reverend Cotton Mather, who has left the fullest account of her case in Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions (1689).

Perhaps the Glovers would not stand for the Puritans’ intolerance and proselytizing attempts; perhaps, as an unlettered woman, Goody Glover could not communicate with the educated, ambitious Puritans. In any case, one common rumor was that her husband on his deathbed had accused her of practicing witchcraft. Such scuttlebutt still did not prevent her and her daughter from securing work as nurse and maid to several Boston families, including John Goodwin, a mason living in the north end of town. Four of his six children, ranging in age from five to thirteen, would ruin the lives of Goody Glover and her daughter.

One day in midsummer 1688, the Goodwins’ 13-year-old daughter, Martha, accused Mary Glover of stealing linen. Overhearing the altercation, Goody Glover, by all accounts possessed of a ferocious temper, unleashed a torrent of “bad language” upon the girl.

Soon after, Martha began to have fits. Three other Goodwin children began to show similar symptoms, often simultaneously: being stricken deaf, dumb, or blind; odd movements of shoulder blades, elbows, wrists, and joints; lying together as if they were attached; cries that they were being cut with knives and hit by blows nobody else could see; and sudden head twisting. Yet, curiously enough, their sleep remained undisturbed, and afflictions rarely took place after 10 p.m.

Doctors consulted by the Goodwin parents, faced with such inexplicable phenomena, resorted to the usual explanation of 17th century Puritanism: “nothing but an hellish witchcraft” could be involved. Now the case began to attract serious attention from the Boston establishment, as five ministers were summoned to pray for the children and magistrates began inquiries. By this time, John Goodwin was recalling the incident immediately preceding the fits, ready to identify the main participant in that event as the woman who had bewitched his children: Goody Glover.

Despite the fact that Goodwin could produce no clear evidence implicating the old woman, Goody Glover was summoned for questioning. Dissatisfied with her answers, the magistrates ordered her and her daughter jailed. Goody Glover was about to learn firsthand the dangers of a criminal justice system driven by fear and vengeance.

The Puritans may have regarded the proceedings as just, but in the cold light of posterity her trial looks like a horror show of superstition, bigotry, and iniquity. The first obstacle she faced involved communication: as a peasant who only knew the Irish language in which she spoke and the Latin in which she prayed, accordingly, she could not recite the Lord’s Prayer in English and this understandable failure counted heavily against her in the minds of the highly literate Puritans.

Goody Glover was also a social fringe dweller in a tightly knit community. Besides the fact that she was one of only a handful of Roman Catholics throughout the English colonies, she was also an indigent widow. As Carol Karisen in Devil in the Shape of a Woman has shown in analyzing colonial witchcraft cases, this latter fact placed her in the demographic group most likely to be executed for witchcraft. Being poor, she could not frighten away potential accusers with the thought of economic retaliation; being a woman, she automatically had fewer rights than any man; and being a widow, she did not even have a husband who could rally support for her in the community.

The Reverend Cotton Mather admitted that Goodwin (later his parishioner) “had no proof that could have done her (Glover) any hurt.” Yet, suffering from the poor memory common to the aged and surely mentally unbalanced by the attention given to the children’s tall tales, Goody Glover offered rambling answers that the five judges regarded as a confession. The tribunal ordered a search of her home by town constables, who soon hauled into court evidence that appeared to clinch the case for the prosecution: “several small images, or puppets, or babies, made of rags and stuffed with goat’s hair, and other such ingredients.” It never occurred to the Puritans that these images might be evidence of crude local folk beliefs.

Also damaging to Goody Glover was the testimony of a woman named Hughes, who claimed that six years previously a neighbor named Howen, just before being “cruelly bewitched to death,” had identified Goody Glover as her tormentor. Just as Hughes was ready to give testimony, she claimed her son began to exhibit the same behavior as the Goodwin children.

It should not be surprising that the Goodwins and Hughes, both neighbors, should accuse Goody Glover of doing them wrong. The “City Upon a Hill” envisioned by Massachusetts founder John Winthrop was now being fractured by acrimony between neighbors.

In the wild, harsher climate of Massachusetts, the old English tradition of helping one’s neighbor was yielding to more individualistic imperatives. In the Goody Glover case, as in the later Salem outbreak, this breakdown in community feeling had devastating results. As John Putnam Demos demonstrates in Entertaining Satan, the charge of witchcraft was often preceded by an incident involving the exchange of goods and services. When the person making such requests was rebuffed, he or she would respond by threatening or cursing – leaving “a residue of bitterness on both sides.”

Reading accounts of the Glover trial is like entering a foreign country: one can easily be confused by an alien language and culture. The Puritan judges, too, appeared to have this problem. A witness testified that Goody Glover had complained the night before the trial that her “Prince” had deserted her. Upon being asked by the judges if she had any “to stand by her,” Goody Glover answered that she had one, who was her “Prince.”

To modern ears, these mutterings are ambiguous: was she praying to the Prince of Darkness or the Prince of Peace, and could she have been reproaching God for forsaking her, as her Saviour had assailed his Father on the cross? Yet, in a case of listening only for what they wanted to hear, the judges never considered these possibilities.

There remained only one way for Goody Glover to escape a death verdict: a determination of insanity by six doctors appointed by the judges. Yet their acid test for mental competency –whether Glover was “craz’d in her Intellectuals” – could hardly pass muster with modern psychiatrists. Their question to Goody Glover about the state of her soul brought the reply, “You ask me a very solemn question, and I cannot well tell what to say to it.”

Moreover, as in the trial, her memory failed her, this time when she could not recite one or two clauses in the Lord’s Prayer. Quick to seize upon difficulty with language and a memory lapse by an illiterate, distraught, perhaps senile woman as evidence, the doctors declared her of sound mind. Goody Glover was then sentenced to death by the judges (one of whom was Deputy Governor William Stoughton, who four years later would also condemn several Salem “witches” to the gallows).

Before she went to her death, however, Goody Glover had to endure two more visits from the implacable fanatic Cotton Mather, who was probably disposed against her because of suspicions that a witch had caused his own son’s death.

After the 25-year-old minister asked twice for permission to pray for her, the condemned woman answered that she could not grant it “unless her spirits (or angels) would grant her leave.” (Mather expressed frustration with their language difference, grousing that in the Irish language the same word represents “spirits” and “angels.”) The intransigent minister, refusing to stop his badgering, prayed for her anyway – but, at the end of this interview, she used her finger and spittle on “a long and slender stone.” Though Mather wrote that he left to others what this might mean, the implication seems clear that she had spells in store for him now, too.

The young Puritan divine was equally disappointed by Goody Glover’s refusal to inform on her alleged confederates. He claimed that she “never denied” her own guilt and that she even identified four others besides herself who attended meetings with “her Prince.” Some historians have pointed to Mather’s unwillingness to reveal these four as evidence of his relative liberalism on the witchcraft issue.

Since Goody Glover was in league with the Devil, this summary of his reasoning states, she must be as committed to spreading lies as her Prince, so why believe her? Yet these seem like highly unlikely scruples for a minister so hell-bent on saving individual souls and preserving God’s Puritan Commonwealth intact from evil. Instead, even while grasping at straws, he was forced to admit that the insane widow “confessed very little about the Circumstances of her Confederacies with the Devil.”

On November 16, 1688, Goody Glover was marched to the gallows, with only Boston merchant Robert Calef, who had stood by her throughout her prison ordeal, accompanying her. According to one historian of this incident, George Francis O’Dwyer, the procession ended at ground which is now occupied by Holy Cross Cathedral, where she mounted a scaffold “built directly where now stands the holy water font in the present Cathedral.”

Samuel Sewall, later a judge at the Salem witchcraft trials, noted the execution in his diary, “About 11 o’clock the Widow Glover is drawn by to be hanged. Mr. Larkin seems to be Marshal. The Constables attend and Justice Bullivant there.” Yet this terse entry does little to recapture the sense of horror, dread, and loneliness the widow must have felt. A convicted witch would be as hated in 17th-century New England as a convicted rapist or serial killer would be in our time. Surely this solitary Catholic was subjected to taunts, insults, and catcalls by these self-righteous Puritans who had never really admitted her into their community.

The crowd clamored “to see if the Papist would relent,” or forsake her faith, according to one observer. “Her one cat was there, fearsome to see. They would to destroy the cat, but Mr. Calef would not permit it.”

Accounts of Goody Glover’s final moments vary, except for her correct prediction that her death would not end the Goodwin children’s afflictions. According to the above chronicler, the old woman died forgiving those who had persecuted herx and protested that it was not she who had persecuted them. Mather, however, not only contended that she claimed that others “had a hand in” the witchcraft, but implied that the old woman named her daughter as one confederate (“one … whom it might have been thought Natural Affection would have advised the concealing of”).

And what of Goody Glover’s daughter, whose argument over a piece of linen had precipitated this communal outburst of superstition and bigotry? She, too, had been clapped into prison to await trial, but her mind cracked under the strain. She died in the spring of 1689, a madwoman victimized by a mad society.

As Goody Glover anticipated, the Goodwin case was far from over. Seeing how eagerly Cotton Mather had accepted her charges, Martha Goodwin and her two bedeviled siblings continued to play upon his credulity, albeit in more spectacular fashion. They would bark like dogs, purr like cats, cry out that they were in a red-hot oven, then that they had been doused with cold water. Above all, they gave grief to their parents: taking more than an hour to dress or undress, contorting their bodies when performing uncongenial menial tasks, and breaking into “the most grievous woeful heart-breaking agonies” upon the slightest criticism from their parents, according to Mather.

To a modern observer, the Goodwin children’s hysterics seem like an early and particularly outlandish form of adolescent rebellion against parental authority. But to the Puritans, and particularly Cotton Mather, the hand of the Devil was in every groan and roll of the eyes. Deciding to observe Martha in isolation from the other children, the Puritan minister — a former medical student who still prided himself on his powers of scientific observation — took her into his home for a closer look and was rewarded for his pains within a few days when she began to act even more erratically. One sign that must have surely convinced him that Satan was at work was that Martha could read from Quaker or Catholic books, but was “immediately struck backwards, as dead upon the floor” the second she opened Mystery of Christ written by Increase Mather.

A year after Martha Goodwin’s torments began, she and the other children must have tired of these games, for the afflictions finally ceased. Naturally, Mather ascribed this happy turn of events to the beneficent effects of his unceasing prayers, in addition to the providential death of another old woman suspected of sorcery. “I am resolved after this,” he wrote, “never to use but just one grain of patience with any man that shall go to impose upon me a denial of devils or of witches.”

With the abrupt end of their troubles, the Goodwin family faded out of history. John Goodwin, grateful for Mather’s tireless efforts to eradicate the Devil from his daughter, became a member of the minister’s congregation. After his death in 1712, his widow remarried two years later and died in 1728.

According to Thomas Hutchinson, historian and later colonial governor of Massachusetts, the Goodwin children grew up to “make profession of religion,” evidently inspired by their torments. One that he knew, who “had the character of a very sober, virtuous woman,” never made “any acknowledgment of fraud” about the incident. Hutchinson did not name the woman, but since he wrote that he knew her many years later, he must not have been referring to Goody Glover’s principal accuser, Martha. The latter became a member of Mather’s church in January 1691, married in 1693, and died at the age of 25 in 1699 as a result of complications in the birth of her fourth child.

As for Mather, he used the Goodwin incident to expound his opposition to skeptics about good and evil spirits in his first major book-length publication, Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions, which circulated throughout New England and the mother country. It won its author acclaim as an especially perceptive observer of the disturbing witchcraft phenomenon and soon caused other Puritan ministers to begin noticing unexplained occurrences in their communities. About 18 months after its appearance, the tribulations of some other young girls in Salem Village who “were in all things afflicted as bad as John Goodwin’s children at Boston” were mentioned by the Reverend John Hale. In June 1692, a Bostonian named Brodbent wrote that “young Mather spoke pretty true when he preached a sermon about two years ago that the old landlord Satan would arrest the Country out of their hands.”

In that same year, the consequences of Mather’s folly began to be felt at last. The Reverend Hale, now a pivotal figure in the Salem witchcraft trials, noted that among the wide variety of documents that judges consulted for precedents during those infamous proceedings was Mather’s tome on the Goodwin case. In his sermons and in Wonders of the Invisible World, Mather played a high-profile role warning Massachusetts of the dangers abroad in the land, all of which he had seen four years before.

When the Salem hysteria finally died out, Mather received a jolting reminder of his sorry part in that time from Robert Calef, who had accompanied Goody Glover in her last lonely moments. Mather’s account of the Goodwin children’s fits, Calef charged, had “conduced much to the kindling of those flames” at Salem that “threatened the destruction of the country.”

Calef’s attack, sarcastically titled More Wonders of the Invisible World, damaged Mather’s reputation so badly that it still has not fully recovered. Mather has had some apologists among historians, who correctly point out that belief in witchcraft was the rule rather than the exception in the 17th century. Nevertheless, even one of the fanatic’s stoutest defenders, Samuel Eliot Morison, was grudgingly forced to concede, “…just as newspaper stories of crime seem to stimulate more people to become criminals, so Memorable Providences may well have had a pernicious power of suggestion in that troubled era.” Another historian, E.W. Taylor, directly assigned the responsibility of witchcraft hysteria to Mather, writing that the Goodwin case was “the direct forerunner of the Salem outbreak,” and that Mather’s “connection with it throws light upon later attitudes.”

Goody Glover resembles the initial victims of the Salem witchcraft trials because she was old, poor, and widowed. Although she did not die strictly because she was a Catholic, her religion made her vulnerable: It reminded the Puritans that she was an outsider in their jealously guarded community. In a year when the Catholic King James II was being removed from his throne, her faith could only inspire misunderstanding and hostility.

A final comparison with the Salem victims reinforces the poignancy of her isolation. In January 1697, Massachusetts held a day of repentance for wrongs committed in the Salem trials. Fourteen years later, the colonial government made amends to surviving defendants and children of victims in those cases. Since Goody Glover had no recorded descendants alive by this time, however, the colony never made any attempt to clear her name. In death, as in life, nobody spoke for the Irish Catholic peasant in Puritan Massachusetts.

The story of Goody Glover originally appeared in the January 1994 issue of Irish America Magazine.

Leave a Reply