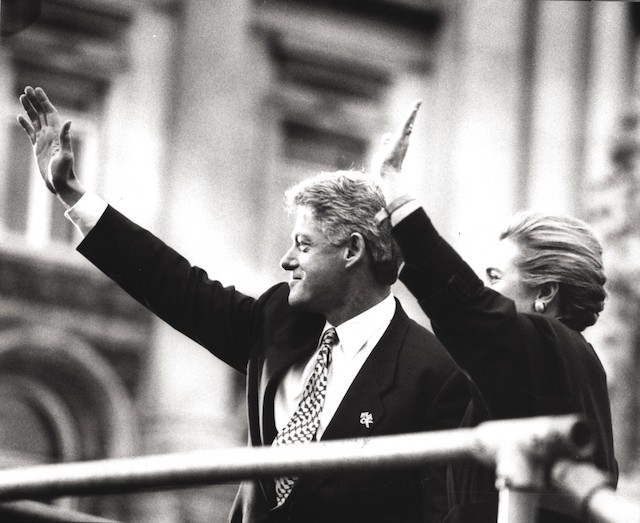

On November 30, 1995, US President Bill Clinton made a historic visit to Northern Ireland.

By Brian Rohan

No American president could have dreamed it better: a clear, crisp night after seven days of rain: 100,000 Catholics and Protestants gathered outside Belfast City Hall, not for an angry protest but rather a peaceful celebration; warm-up act by Belfast’s native son and favorite musician, Van Morrison; and grown men and women shedding tears of joy in front of the world’s media. All there for one reason: Bill Clinton.

It was the night of November 30, and Clinton, the first U.S. president ever to visit Northern Ireland, was in Belfast to turn on the Christmas tree. The town was in its 15th month of ceasefire, for which Clinton found himself recipient of much credit. One woman held up a sign reading, “Welcome Mr. Clinton, Angel of Peace.”

Bosnia, Whitewater and Newt Gingrich must have seemed light-years away.

As New York Times op-ed writer Maureen Dowd put it, “The irish gave [Clinton] the best two days of his presidency. It was the presidency Bill Clinton had dreamed of but never experienced.”

Naturally, every step of the trip had been choreographed, down to the President’s diplomatic choice of colors when buying apples at a Shankill Road fruit stand: two red and two green. And the thousands of American flags which greeted Clinton at every stop were no accident either: the White House advance team saw to it that for every news camera there was at least one flag, maybe two.

Still, even Clinton’s harshest critics and the most jaded of journalists were amazed at the genuine outpouring of love for an American President in a land which had failed to embrace one on this scale since Jack Kennedy.

“It’s a great day, an amazing day,” said Peter King, a Republican party Congressman from Long Island and a normally-staunch critic of the Clinton Administration. King, who has visited Ireland at least a dozen times since the 1970s, told reporters as he looked out on the crowd in Belfast, “There are people here who two years ago were killing each other. I mean literally killing each other It’s amazing.”

Every step of Clinton’s trip was planned to underline the importance of holding the peace, something which the current administration has made a priority since May 1992, when Clinton the candidate vowed to a group of Irish American leaders in New York that, if elected, he would reverse the laissez-faire attitude by successive American governments toward Ireland.

The Northern Ireland trip was the finishing touch on a process begun almost two years previously when, in January 1993, months before there was even a hint of an IRA ceasefire, Clinton defied the British Government as well s many in his own State Department and granted Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams a visitor’s visa to the U.S.

Now, with the ceasefire seemingly solid and hints of a political process growing, Clinton’s decision didn’t seem as ill-conceived as his critics had proclaimed.

“If President Clinton had listened to the likes of me, he never would have seen his Irish triumph,” wrote Mary McGrory, an influential columnist for the Washington Post. “I was one of those who thought he was mad to let in Gerry Adams, the IRA propagandist. But he paid no attention to us. Adams was the key, and last week, Clinton brought genuine joy to Belfast, one of the planet’s most cheerless sites.”

At Mackie’s, a textile factory in west Belfast which had been chosen because of its religiously-integrated workforce, Clinton told a crowd of several thousand Protestants and Catholics that they must continue to hold the peace.

“You must stand firm against terror,” he said. “You, the vast majority, must not allow the ship of peace to sink on the rocks of old habits and hard grudges. …

“You must say to those who still would use violence for political objectives: you are the past, your day is over.”

The message would be driven home at every stage of the two-day trip. In Derry, a much different city than it was in the late-1960s, where desperate social conditions led to civil rights marches and, in 1972, to the tragedy of Bloody Sunday, the President pledged his commitment to further economic development and assistance: “I pledge that we will do all we can through the International Fund for Ireland and in many ways to ease your load.”

Afterward, inside the Guildhall, the President and Mrs. Clinton dedicated a new chair at the University of Ulster in honor of the late Speaker of the House, Thomas (“Tip”) O’Neill.

And in Dublin, where a crowd of 80,000 at the College Green on Friday, December 1, were determined to try and better the crowd enthusiasm up north, Clinton said, “To all of you who asked me to do what I could to help peace take root, I pledge you America’s support. We will stand with you as you take risks for peace.”

Those risks for peace were never so apparent as when, on December 7, five days after Clinton left Ireland, the IRA released a rare statement in which the request that its arms be surrendered was called “ludicrous.” The statement was in response to a hastily-engineered agreement by British Prime Minister John Major and Republic of Ireland Taoiseach (Prime Minister) John Bruton on the eve of Clinton’s three-day trip to London, Belfast and Derry; the agreement called for an Americanled neutral body to seek the decommissioning of the IRA and its loyalist counterparts, separately from any political talks.

This agreement, which critics charged was a “fudge” aimed at appeasing headline-hungry White House Staffers, had nonetheless been viewed as a huge triumph for the Clinton Administration, which sought to place Clinton ally and former Senator George Mitchell at the head of the new decommissioning body. Patrick Sloyan, the Pulitzer Prize – winning Newsday reporter, wrote, “[Clinton] appeared dynamic and skillful in London, where Prime Minister John major conceded leadership to Clinton on two issues that have defied solution: Bosnia and Ulster. Both Major and Prime Minister John Bruton picked former Senator George Mitchell, a Democrat from Maine, to head commission charged with talking the IRA and the Protestant paramilitaries into turning over at least some of their weapons by the end of February. In doing so, Major and Bruton ceded to Washington responsibility for ending The Troubles in Ulster.”

By December 7, however, the IRA as well as the British Government made it clear that a solution would not come so easily. The IRA oppose the surrender of its arms before Sinn Fein’s inclusion in all-party talks, but the British Government and most unionist politicians refuse to hold such talks with Sinn Fein until the IRA has surrendered arms.

Regardless, all of Ireland seemed to be inspired by Clinton’s visit that perhaps there is a way out of the impasse. As Irish America goes to press, the commission led by Mitchell has been holding meetings, and it is hoped there will be some movement before the intended staging of all-party talks in late February.

“Those who do show the courage to break with the past,” said Clinton during his speech at Mackie’s, making a thinlyveiled reference to Sinn Fein and the IRA, “are entitled to their stake in the future.”

This comment received one of the very few outbursts of negativity during the Clinton visit – the shout of “Never!” from a member of the audience, Mr. Cedric Wilson of the Reverend Ian Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). With this exception, Clinton’s message, that “engaging in honest dialogue is not an act of surrender, it is an act of strength and common sense,” seems to have taken hold even in some of Ireland’s more resistant pockets of distrust.

“Surely,” said that President, referring to the 25 years of violence in a tone that was a confident as it was hopeful, “there is no going back.”

President Clinton ended his visit to Derry City by formally inaugurating the Thomas P.O’Neill Visiting Chair in Peace Studies, sponsored by the American Ireland Fund through a $250,000 grant, as a tribute to the former Speaker of the House. The Chair is part of a joint United Nations University and University of Ulster initiative for the study of ethnic conflict and resolution.

Addressing an enthusiastic crowd inside the Guildhall, the President recalled that “Tip O’Neill was fundamentally a man of the people – a bricklayer’s son who became the most powerful person in Congress and our nation’s most powerful champion for working families.

“Speaker O’Neill,” he said, “was a good friend of the cause of peace in Ireland. Though sorely missed he will be long remembered, and the O’Neill Chair in Peace Studies will be a fitting tribute to his long life and legacy. For Tip O’Neill knew that peace must be nurtured by a deeper understanding among people and greater economic opportunity for all.”

The President ended the inauguration ceremony by issuing a challenge to the people of Derry to set an example to the rest of the world: “American has always been about three great things,” the President said, “love of liberty, belief in progress, and unity. And the last is by far the most difficult and is a continual challege for us – I pray through this chair and through your example you will become a model for the rest of the world, because the world will always need models for peace.”

The Little Girl Who Stole the Show

Only one person received better press than Bill Clinton during the presidential visit to Ireland in November – a chubby-cheeked, 9-year-old Catholic girl who stole the show at the scene of one of Clinton’s major speeches.

Before the President’s speech at Mackie’s, a west Belfast textile factory celebrated for its religiously-integrated workforce, the 9-year-old, Catherine Hamill, read from a school contest-winning essay which asked, “What does peace mean to you?”

“My first daddy died in the Troubles,” said Catherine in a direct, unwavering Belfast voice, to a hused audience of several thousand. “It was the saddest day of my life.

“Now it is nice and peaceful,” she continued. “I like having peace and quiet for a change instead of people shooting and killing. My Christmas wish is that peace and love will last in Ireland forever.”

There were few dry eyes in the house. Even John White, a loyalist leader who spent two decades in prison for killing a Catholic man and the man’s Protestant girlfriend, was seen wiping away tears.

Catherine’s speech occurred only five hours into the President’s two-day Irish visit, yet for the duration of his stay he repeatedly recalled “that beautiful child,” and how his own speeches, in the wake of hers, seemed “superfluous.”

Hamill’s father, Patrick, was killed by two masked loyalists who burst into their west Belfast home on September 8, 1987, when Catherine was less than a year old. “They weren’t looking for anyone in particular,” explained Catherine’s mother, Laura Hamill.

“They just wanted a Catholic man, and we’re so near to their area. They shot Patrick in the head, neck and chest right in front of me.”

A 10-year-old Protestant schoolboy, David Sterrett, also read from his essay, which read in part, “[Peace] means I can play in the park without worrying about getting shot.”

But it was acknowledged by all that Catherine was the star of this show. Two weeks after President Clinton turned on the Christmas tree lights in her hometown, Britain’s Daily Mail newspaper, Virgin Airways and the Fitzpatrick Hotel chain flew Catherine and her family to U.S. to be among the Clinton’s invited guests at the tree-lighting ceremony at the White House. ♣

This article by Brian Rohan originally appeared in the February 1996 issue of Irish America.

Leave a Reply