Remembering the five Sullivan brothers, World War II sailors who, serving together on the USS Juneau, were all killed in action on its sinking around November 13, 1942.

November 8, 1942: the largest U.S. naval task force yet assembled for the battle of Guadalcanal sales out of Noumea, New Caledonia. Among the American warships was the year-old, light cruiser U.S.S Juneau. One can only imagine the thoughts of those young sailors as they headed North – the future uncertain. Yet on the Juneau, four young man – all brothers certainly gave some thought to a fifth brother, for November 8 was the birthday of Madison Abel Sullivan. He was 23.

At first, this mission to reinforce Guadalcanal, a jungle Island U.S. Marines were struggling to wrest from the Japanese, was uneventful. Arriving November 11, the Vanguard of the destroyers and cruisers scoured the waters where the “Tokyo Express” (the nickname given to the enemies resupply and attack runs) might be expected. No Japanese warships were found. The U.S. transport arrived and proceeded to unload the urgently needed men and material. On November 12, the screening U.S. warships, in combination with Marine fighter planes from Guadalcanal‘s Henderson airfield, destroyed an attacking formation of Japanese aircraft. U.S. losses were light.

As evening approached, American reconnaissance detected the approach of a large Japanese task force. Ironically, the Japanese had decided to carry out a full-scale push to reinforce their troops on Guadalcanal at the same time as the Americans.

The U.S. transport, not entirely unloaded, hastened south to safety. Although out numbered and outgunned, the Americans were forced to meet the enemy with the ships available. The battle would take place at night. This element would also favor the Japanese. For their night fighting tactics were excellent. But, the Americans had three things in their favor – pre-warning, radar and Rear Admiral Daniel J Callaghan, whom Samuel Elliot Morrison (The Struggle for Guadalcanal) describes an “austere, modest, deeply religious, hard-working and conscientious officer who possessed the high personal regard of his fellows and the love of his men, “Morrison might have gone on to add that Callaghan was Irish and perhaps the proverbial “luck of the Irish” might prove a fourth advantage.

In fact, in addition to Admiral Callaghan and numerous other Irish-Americans – the five Sullivan’s included – scattered throughout the ships of this task force. The American battle group would also include among its destroyers the U.S.S O’Bannon. And, as an extra measure, it should be noted that Madison Abel Sullivan had been named after a great grandfather who had been born on St. Patrick’s Day no less.

Yet, luck – even Irish luck – would be a capricious lady this night. Admiral Callaghan might have suspected as much since many of the Japanese ships he was about to face in combat had slipped southward through the waters off New Ireland.

Despite having radar, the American task force nearly collided head-on with the Japanese ships. It was approximately 1:45 a.m. There was no moon. Suddenly searchlights illuminated friend and foe alike. Guns of various calibers erupted in devastating barrage at close range. The opposing formations became a confusing melee. The Americans suffered quickly and grievously. One by one, the U.S. ships were sunk are disabled. Only the destroyers Fletcher and U.S.S O’Bannon along with the cruiser Helena escaped relatively unscathed. The first 15 to 20 minutes with the deadliest. By 2:15, the battle was essentially over.

Five out of 13 U.S. ships have been sunk or were sinking. Five more were seriously damaged. Out a 14 ships, the Japanese had lost two destroyers and would lose a crippled battleship the next day. The Americans also lost many men, among them Admiral Callaghan. The Juneau had barely survived, taking a torpedo hit on its forward port side, leaving a gaping hole and nearly severing it’s keel.

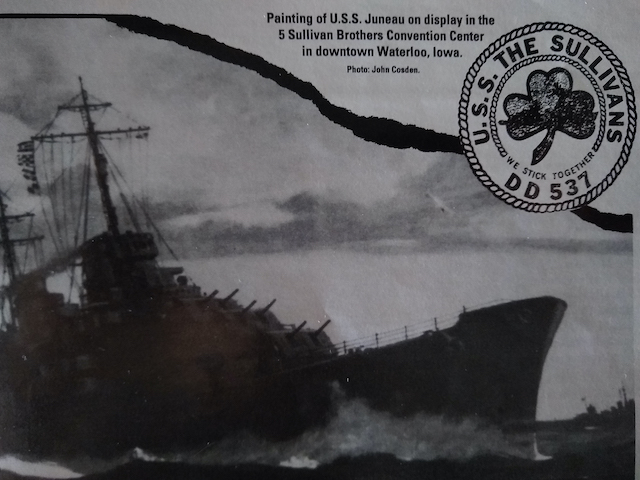

At daybreak, the six U.S. ships that could still move huddled together and headed back to their basis. At 11:00, under sunny skies in a calm sea, a torpedo (fired by Japanese sub 1-26) struck the Juneau on its vulnerable port side in the vicinity of the forward magazine. In his action report, Captain Gilbert C. Hoover, the senior surviving American officer, described what he saw: “When the torpedo hit, there was a large single explosion and the air was filled with debris, much of it in large pieces… The whole ship disappeared in a large cloud of black, yellow black, and brown smoke. Debris showered down among ships of the formation for several minutes after the explosion to such an extent as to indicate erroneously a high-level bombing attack.”

Lieutenant Commander H.E. Schonland, who was acting commander of the San Francisco steaming 800 yards behind Captain Hoover’s Helena reported, “It is certain that all on board perished.”

Captain Hoover had to make a quick decision. Should you ask more of his dwindling, battle-damaged in anti-submarine operations and search for survivors? A friendly B-17 investigating the explosion helped him decide. He signaled it to report the location of the Juneau’s sinking, and then he sent his ships out of the dangerous waters. Unfortunately, the B-17’s report never got through. Moreover, Lieutenant Commander Schonland was wrong – there were survivors.

Different sources estimate the numbers between 60 and 150. But, among them was George Sullivan, the oldest of the Sullivan brothers. Gunner’s mate second class Allen Clifton Heyn was one who lived to tell the story, which he did in an interview he recorded for the Navy, September 23, 1944. Heyn was just 16 at the time; he had lied about his age when he enlisted. He recalled tremendous suffering and death. Badly burned men, coated in diesel oil; many with gaping wounds were battered by the burning sun and sudden rain squalls. They were delirious from hunger and thirst. And then the sharks came, picking off the defenseless. One by one, the survivors succumbed. By the ninth day, only 10 men remained alive.

As for the last Sullivan brother, Heyn reports his death as follows: “[One] night after dark, George Sullivan said he was going to take a bath. And he took off all his clothes and got away from the raft a little way and the white of his body must’ve flashed and showed up more because the shark came and grabbed him and that was the end of him. I never seen them again.”

Who were the Sullivan brothers? What path had led them to such a horrible death so far from home? Fifty years after this tragedy, what is their legacy?

For the most part, the answer to these questions can be found in Waterloo, Iowa, a town of approximately 75,000 people (47,000 in1943) in the northeast quadrant of that Midwestern State. Although located in the heart of America’s “bread-basket” Waterloo depended on it to economic survival during World War II on three industries: meat packing, farm equipment, and rail freight. The Cedar River, as it did then, slices southeasterly through the center of town, bordered by the factories and tracks of these same industries. Although today, the western side supports the familiar trappings of modern American suburbia – malls, fast food restaurants, and expressways – the east side remains a semblance of its former self. For it was among the working class neighborhoods of the east side that the family of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas F. Sullivan had its beginning.

Born in 1883, Thomas F. Sullivan, father of the five boys, was three things: Irish, Catholic, and a workingman. His grandfather, for whom he was named, had been born in Ireland and had brought an Irish born bride, Bridget, with him to America. When Tom Sullivan married Alleta M. Abel on February 4, 1914, theirs was a Catholic wedding at St. Joseph’s in Waterloo. The new Mrs. Sullivan also hailed from Irish stock, her mother was Mae McGuire. Their marriage certificate lists Tom’s occupation as a railroad man. In fact, he worked for the Illinois Central Railroad (now the Chicago Central and Pacific) for four decades. In 1943, he is reported to have told shipyard workers in Philadelphia that he “had not lost a day of work and 38 years.” Tom and Alleta lost no time in starting a family together.

On December 14, 1914, George Thomas Sullivan was born. Fourteen months later, on February 18, 1916, brother Francis Henry came along. Then, a sister followed – Genevieve Marie, born February 19, 1917. The next year a third boy joined the growing family – Joseph Eugene Sullivan born on August 28, 1918. The fourth boy Madison Abel, entered the world on November 8, 1919. The youngest son, Albert Leo, arrived on July 8, 1922. Another child – a girl – Kathleen May was born April 1, 1931, but died of pneumonia just five months later on September 28. The death of this infant foreshadowed the greater loss that lay ahead.

From every indication, the Sullivan kids differ little from millions of other working-class youngsters growing up in America during the 1920s and 30s. Their father worked long hours each day but still found time to take the boys hunting, and fishing; their mother and grandmother, for Alleta’s mother was widowed and had moved in, washed, cooked, and cleaned while seeing to it that the kids attended church; and the kids themselves, played, went to school, and got into mischief.

Frank Zubak, who still lives in Waterloo and served during World War II in the Army’s 6th Armored Division in Europe, remembers a bit of mischief that Francis “Frank” Sullivan got into in the second grade at Saint Mary’s, the Catholic school the Sullivans attended. “We had Sister Maxine. She was a Franciscan nun, and she was tough. One day, Frank and I were chasing each other around the room and Frank knocked over a Blessed Mother statue. Sister gave him the ruler that day.”

As the Sullivan kids grow older, the realities of the hard times accompanying the Depression no doubt at home. It was about this time that staying in school – as opposed to working to help out at home – became harder. There are no records of the boys having finished high school, although Genevieve did. Of course, in the 1930s not finishing high school was not unusual.

Bob Pavich, a Saint Mary’s parishioner who hung around Al (Albert) and Matt (Madison) when they were teenagers, remembers that they used to play baseball, football, and basketball, on the field next to the Sullivan’s home at 98 Adams Street. He also remembers their trying to earn a buck in those days, “Matt and I, and some of the other fellas used to caddy out at the old Sunnyside Country Club.

Of course, Pavich remembers spending some of that money too. “There used to be a confectionery, Neubauer, and Crowder, at the corner of E. 4th and Saxon. It had a soda fountain where a lot of kids would gather. Downstairs was a place called Kate’s Kitchen where there was a jukebox and where we could dance.”

Around this time, George and Frank, the two oldest boys, decided to try their fortunes outside of Waterloo. On May 11, 1937, they both enlisted in the Navy, serving on the U.S.S Hovey until their discharge in June 1941.

It was while the older boys were away that Paul Hamilton, a Waterloo resident, who was 19 at the time and had just finished high school, got to know “Red” (Joseph) Sullivan. The red-haired, freckled-faced middle son of Tom and Alleta had joined the Black Hawk motorcycle Club in 1939. Hamilton recalls, “The motorcycle club group out of the motorcycle repair garage run by Paul Brokaw. It was like a social club and a school. If you had a question, Paul would get on the floor and draw a picture with chalk to explain how things worked.”

Hamilton and Red Sullivan hit it off from the start. Hamilton remembers Red’s easy-going friendly nature, “he would do anything for you. He even tried to put in a good word for me at Rath’s [Rath Meat Packing Co.]”

Another sister Genevieve worked at the John Deere Tractor factory. Rath’s eventually became the principal employer of all five of the Sullivan boys. When George and Frank returned to Waterloo after their Navy discharge, they too get jobs at Rath’s, joining Matt, and Al. The Sullivan brothers were together again. But, one thing has changed. Baby brother Al was a husband and father.

Albert Leo Sullivan married Katherine Mary Rooff on May 11, 1940, at Sacred Heart Church in Waterloo. The following February, James “Jimmy” Thomas Sullivan was born. No doubt the other boys would have settled down, married, and had families of their own if the times had been ordinary. But, on December 7, 1941, the extraordinary occurred.

Later, when news reached the Sullivan boys that Bill Ball, a friend of theirs from Fredericksburg, Iowa, had been killed at Pearl Harbor in the attack on the U.S.S. Arizona, they were determined to enlist. They placed one condition on their enlistment – they must be allowed to stick together. The Navy honored their request. On January 3, 1942, they were sworn in at Des Moines and sent to the Great Lakes Naval Training Center.

Paul Hamilton, who later served with the 113th Cavalry in France and Europe, remembers the day Red Sullivan left. “I was on the roof of the motorcycle shop. It must have snowed because I was scraping ice and snow from the roof. He came by, we shouted goodbye, and he left. That was the last I saw of him.”

Hamilton still has a couple of Red’s letters. Although undated, a letter written on Juneau stationery contains a sentence that stands out: “Tell Paul [Brokaw], I’ve still got the rabbit’s foot he gave me when I left, and that I think it’s brought me good luck also.”

When the U.S.S. Juneau went down, the Navy, as was the policy During World War II, kept its sinking secret. In the weeks that followed, the boys’ letters to 98 Adams Street stopped. However, the Waterloo Courier (January 15, 1943) reported that unofficial word of the boys’ deaths had reached Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Sullivan via a letter from a “Nebraska boy, writing from Chicago while awaiting assignment.” Still, until official word reached them, the family clung to the hope that one or all of the boys had survived.

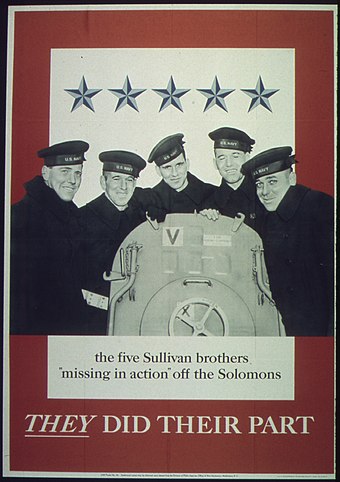

What followed, in the meantime, was an outpouring of publicity and public sympathy. George, Frank, Red, Matt, and Al were national topics – they had become “the fighting Sullivan brothers,” Letters and telegrams from all over arrived at the Adams Street home; the Iowa Senate and House adopted resolutions of tribute to the brothers; President Franklin D. Roosevelt, echoing the sentiments of Lincoln’s letter to Mrs. Bixby, sent a letter of condolence to Mrs. Sullivan; Mr. and Mrs. Sullivan, accompanied often by daughter Genevieve, gave radio broadcasts and made speaking appearances at shipyards and war plants, urging more production to help other sons still fighting. Pope Pius XII sent a silver religious medal and rosary; and at the Rath Packing Company, C. Donald Meeker, manager of the employees’ cafeteria, carved 8-inch tall soap figures of the five boys standing on the barrel of a large naval gun, with the larger figure of a protecting sailor “spirit” watching over them.

In the year that followed, three important events occurred to perpetuate the memory of the five hard-working, fun-loving Irish-American boys from Iowa.

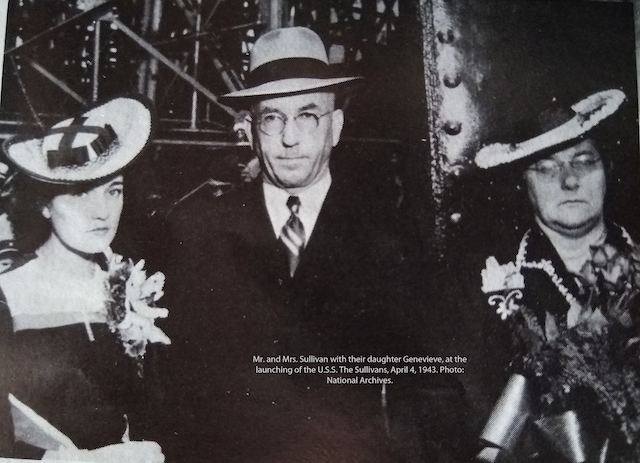

On April 4, 1943, Mrs. Thomas Sullivan christened a new destroyer, U.S.S. The Sullivans, at the Bethlehem Steel Shipbuilding Yard in San Francisco. Today, having fulfilled its missions in two wars (World War II and Korea), The Sullivans survives, moored at the Naval and Servicemen’s Park in Buffalo, New York, as a memorial to the five brothers.

On June 14, 1943, Genevieve Sullivan reported to Hunter College, New York, for WAVE training. Although she was to be trained in recruitment (certainly no combat role), nevertheless, the image of the only surviving child of a Navy family joining the Navy remains a poignant one.

On August 8, 1943, Frank Knox, Secretary of the Navy, sent an official letter to Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Sullivan, the first paragraph of which reads: “Eight months have now elapsed since the loss of the U.S.S. Juneau, during the battle of Guadalcanal, on 13 November 1942. This lapse of time, in view of the circumstances surrounding the disaster as officially reported b close witnesses, forces me reluctantly to the conclusion that the personnel missing, as a result of the loss of the Juneau, were in fact killed by enemy action.” The style is convoluted, but the words all too simple – your sons are dead.

However, the same instrument, which extinguished the hopes of the Sullivan family in 1943, also immortalized the five Sullivan brothers – perhaps for all time. As a last full measure of their devotion, the Sullivan Law prohibiting brothers from serving on the same ship was passed.

As part of the chain of festivals from Leitrim to Beara in the summer of 2003, a flotilla of naval ships arrived in Glengarriff, County Cork on August 29. Chief among the ships was the Naval destroyer U.S.S. The Sullivans, which moored near Castletownbere for the 400th anniversary of O’Sullivan Beara’s historic march from Beara to County Leitrim.This article was originally published in Irish America Magazine in March 1992 and updated in November, 2025

NOTE: O’Sullivan/Sullivan Clan Gathering 2026

The O’Sullivan/Sullivan Clan plans to establish a new World Record for the largest gathering of people with the same surname in Castletownbere County Cork, on May 30, 2026. The clan gathering will be hosted by the Chieftain of Clan Sullivan, Kelly Sullivan, granddaughter of Albert Sullivan (one of the five brothers who were killed in action on November 13, 1942) from Waterloo, Iowa.

The attempt will be part of a three-day celebration of heritage and kinship, featuring a full programme of family friendly activities, throughout the Cork and Kerry sides of the Beara peninsula over the May Bank Holiday Weekend (May 30 – June 2, 2026).

Those interested in participating in setting the new World Record must register their attendance through the official website: osullivanclan.org. To date, more than 1,320 have already registered, raising high the O’Sullivan/Sullivan Clan’s expectations of beating the current World Record established on September 9, 2007, when 1,488 members of the Gallagher Clan gathered in Letterkenny, Co Donegal.

There are two major branches of the O’Sullivan/Sullivan Clan: the O’Sullivan Mór, who are associated with the Iveragh peninsula in Co Kerry; and the O’Sullivan Beare, who are associated with the Beara peninsula in Co Cork and Kerry. It is expected that both branches will be represented at the event, along with O’Sullivan/Sullivans from all over the world.

Many O’Sullivan/Sullivans who left Ireland settled in America. Kelly Sullivan is descended from some of those who left Adrigole, on the Beara peninsula, in the Famine era. They settled in Iowa. Kelly’s grandfather Albert was one of the five Sullivan brothers – along with George, Francis, Joseph and Madison – who lost their lives when the USS Juneau was sunk in the naval Battle of Guadalcanal during World War II.

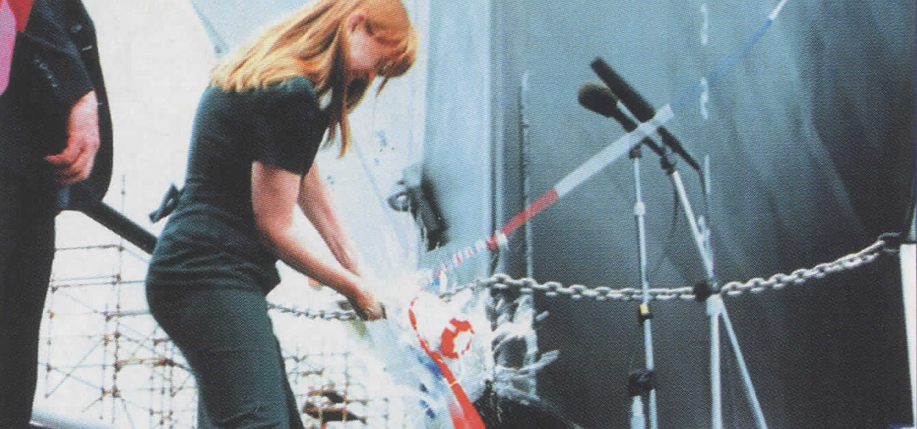

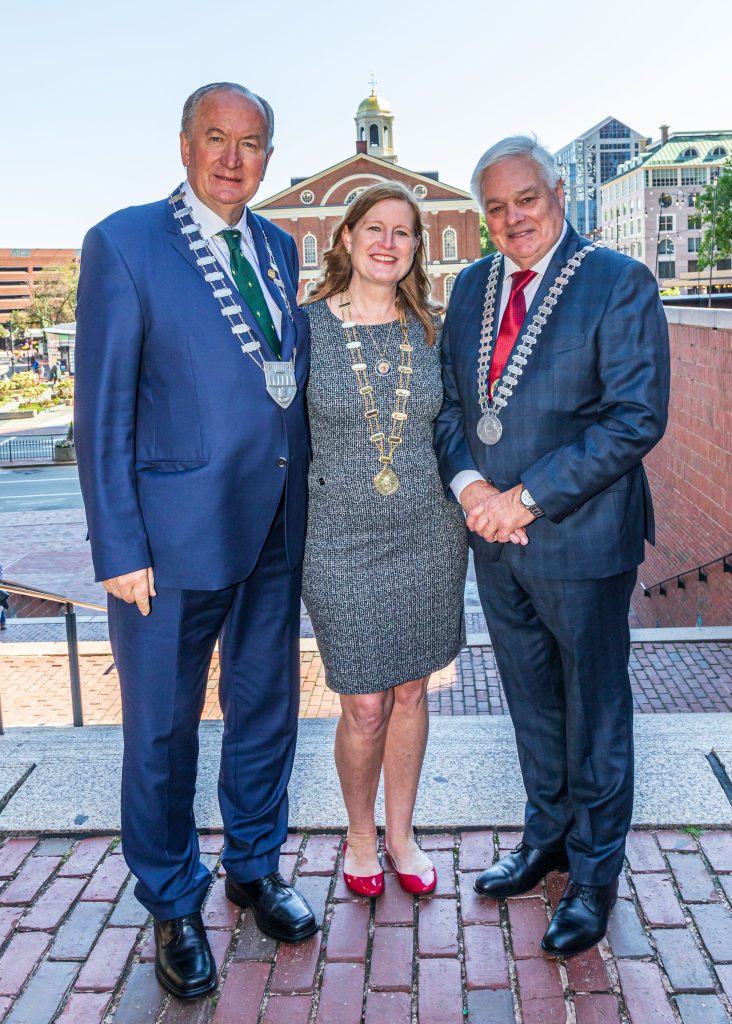

Kelly is sponsor of the US Navy ship named in their honour, USS The Sullivans DDG 68, and accompanied the vessel when it visited the Beara peninsula in 2003. Twenty years later, in September 2023, Kelly was presented with the O’Sullivan/Sullivan Clan Chieftain chain of office by the Cork and Kerry County Mayors on the steps of City Hall in Boston.

The 2026 O’Sullivan/Sullivan Clan Gathering will feature tours to various sites associated with the O’Sullivan Beares, including the ruins of their stronghold at Dunboy, a few miles west of Castletownbere, and the site of their second castle in Ardea, Tousist.

After the Irish defeat at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601, Dunboy Castle was levelled by the English, and the Clan Chieftain, Dónal Cam O’Sullivan Beare, led his people on the Long March to Leitrim. This event is commemorated in the longest walking route in Ireland, the 500km Beara/Breifne Way.

Full information on the 2026 O’Sullivan/Sullivan Clan Gathering and World Record attempt is available at osullivanclan.org.

Irish & Americans of Irish heritage have been important parts of the U.S. military from the Revolutionary War right up to today. Irish immigrant soldiers were crucial to the eventual Union victory in the U.S. Civil War. Irish Americans volunteered for service in WW I with a mind of finally becoming “full” citizens in America, which the achieved in the post war years. In all of America’s wars, soldiers of Irish heritage represented an outsized number of acts and awards for valor.

There is no such thing as “The Sullivan Law” that’s a myth.