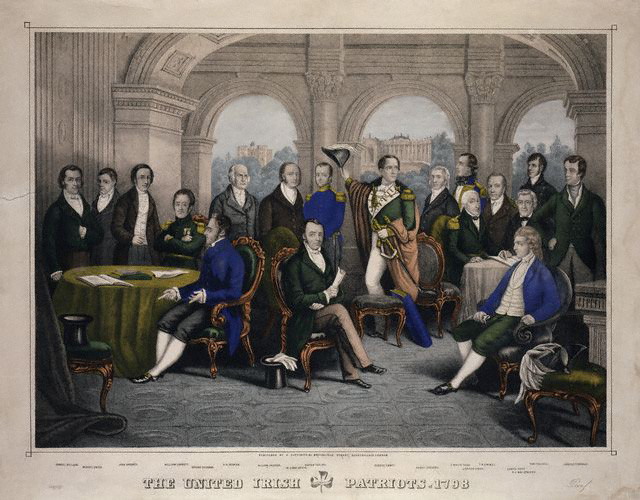

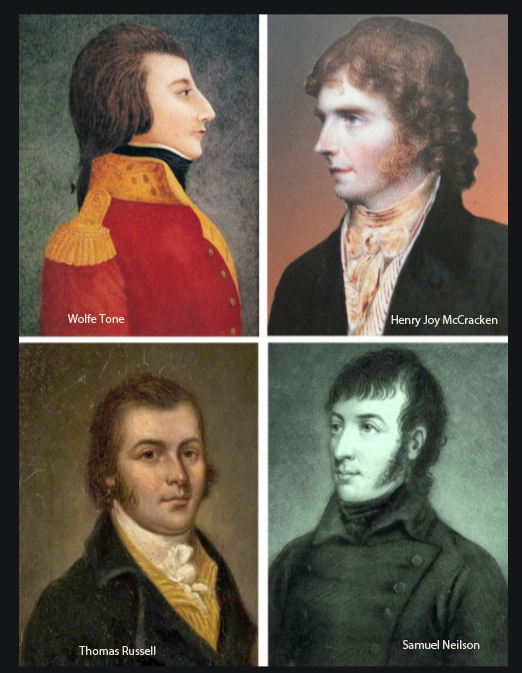

The Society of United Irishmen, founded in Belfast on October 26, 1791 by radical political thinkers, including Theobald Wolfe Tone, Hamilton Rowan, Samuel Nellson, Henry Joy McCracken and Thomas Russell, the organization’s declared objective was “equal representation of all the people in parliament” and the establishment of a political system that would include all religious denominations.

In the late spring and summer of 1798, over 30,000 people, mostly peasant men, women and children, were wiped out in a frenzy of battles, murders, reprisals and counter-reprisals in one of the bloodiest and most dramatic events in Irish history. One of the earliest attempts by Irish nationalists to shake off the burden of British colonial rule, the United Irishmen rebellion of 1798 ended in total defeat for the insurgents and the capture and execution of most of the movement’s leaders. The immediate results were a disaster for nascent Irish nationalism, but the long-term consequences were momentous: barely three years after the rising was quashed by government forces, the Irish parliament was abolished and enforced union with Britain was imposed on the people of Ireland. The insurgents who took up arms and faced down the government’s Yeoman armies in Wexford, Wicklow, Kildare, Mayo and Antrim could not have realized it, but their rebellion in 1798 would resound through the development of Anglo-Irish relations for the next two centuries, and right up to the present.

The Background

The Irish parliament in the 1790s was exclusively Protestant, despite the fact that Catholics comprised a majority of the population, Many anti-Catholic laws had been gradually abolished through legislation after the establishment in the early 1780s of the parliament, but real political and commercial power, including control of the army, the country’s finances, education and trade, remained in the hands of a Protestant oligarchy notorious for self-interest and lack of concern for the country’s majority population.

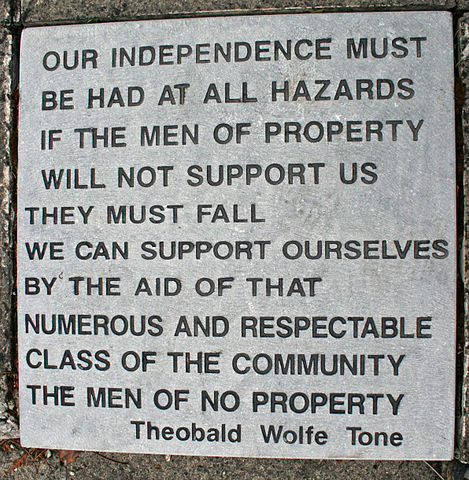

Into this political culture of restricted representation and corrupted leadership came the Society of United Irishmen. Founded in Belfast in 1791 by radical political thinkers, including Theobald Wolfe Tone, Hamilton Rowan, Samuel Nellson, Henry Joy McCracken and Thomas Russell, the organization’s declared objective was “equal representation of all the people in parliament” and the establishment of a political system that would include all religious denominations. Tone, a young Protestant barrister, and the other founders of the United Irishmen were much influenced by the wave of republicanism sweeping across Europe and America. The American War of Independence had taught that self-rule was not necessarily unobtainable, and the lessons of the French Revolution of 1789 were also carried to Ireland by young radicals who had previously despaired of reforming the Irish political system.

With revolution in the air, Tone understood the necessity of a broad, inclusive support base to underpin a successful political reform. He looked to the country’s peasantry, which would naturally support the establishment of a representative system, but significantly, also to the Presbyterian community in Ulster, which lay economically in the middle ground between the Catholic majority and the Protestant establishment.

With a long history of emigration across the Atlantic, the Presbyterians were also very enthused by the American Revolution and had begun to seek concessions from parliament regarding economic and political rights, and also for the removal of remaining anti-Catholic laws.

The United Irishmen were initially reformers operating to better the political system. But with the outbreak of war between Britain and France in 1793, the increasingly well-supported organization was outlawed by a government fearful of any group with links to French radicals, and the United Irishmen were driven underground.

Early in 1795, the United Irishmen – originally a “brotherhood of affection,” and now technically a revolutionary body – was reorganized as a secret society, and in June, while the organization secretly prepared for war, Tone left Ireland for America to contact representatives of the French revolutionary government and enlist their aid in an Irish rebellion.

His mission was a success. But the 14,000 strong French fleet that set sail to invade Ireland in December 1796 was dispersed by a storm off Bantry Bay, Co. Cork, and the expedition miscarried. Fueled by panic, the government reacted to the attempted invasion with a vicious campaign against the United Irishmen and their supporters, particularly in the midlands and southern half of the country. Reports that Napoleon was readying a second invasion fleet worsened the fears of the establishment and its supporting aristocracy. It seemed clear that the United Irishmen would not stop until Ireland was in the hands of a new government and that the country was moving closer to outright rebellion.

The Rebellion

In March 1797, the authorities acted, and in a series of raids, the United Irishmen’s most senior figures were arrested. With martial law declared. the army were given “free quarters” in private homes in districts which supported the rebels, and embarked upon a brutal campaign of intimidation, looting, arms searches and “pacification measures.” Parts of Ulster and north Leinster, in particular, were singled out, and floggings, half-hangings, and burnings became common. In Kildare, Athy, Maynooth and Celbridge, homes of suspected United Irishmen and sympathizers were burned.

In Wicklow, victims were tied to a specially-designed frame before being publicly tortured. Even General Ralph Abercromby, the new Commander-in-Chief of the army, was appalled at the soldiers’ treatment of the general populace: “it can scarcely be believed,” he wrote. The army, he added, was “in a state of licentiousness which must render it formidable to everybody but the enemy.”

When the army was loosed on Dublin -considered a bastion of United Irishmen support — and discovered a substantial arms cache in the process of quelling opposition, the authorities began to believe the immediate threat of an uprising had faded. Even those United Irishmen who looked to France to support a rebellion despaired of action, since Napoleon had turned his attention away from an Irish invasion and toward Egypt.

As it turned out, they were all wrong. A rising — or rather a series of risings — did break out, and although up to 100,000 insurgents were involved across the country there was little coordination and organization, and the effect was one of a series of strong punches to the body of government rule, rather than a single knockout blow.

In Kildare on the night of May 23rd, rebels attacked and destroyed the military garrison at Prosperous. Over a thousand men, armed mainly with pikes — long, spearlike instruments topped with a metal spike — then attacked Naas, but retreated with over 300 dead. In the south of the county, the bravery of the insurgents caused the army to retreat, and soon Newbridge, Kildare town, and Monasterevin were under rebel control.

Armed columns advanced into Offaly and Laois, and towards County Meath. But after a failed attempt to lay siege to Dublin, the initial momentum of the rising in Leinster began to wane. More than 350 were killed at historic Tara in Co. Meath. Over 400 more were massacred in Co. Kildare as they were about to negotiate a surrender.

Atrocities were commonplace, on both sides, and would remain a brutal feature of the rebellion. At Dunlavin, Co. Wicklow, 34 prisoners were executed in the town park. In Carnew, more than 30 more were slaughtered in a local handball alley. In Wexford, rebels chased down and killed government supporters, and imprisoned hundreds of suspects.

The north of the country, which had suffered particularly badly under army pacification, was soon caught up in the wave of rebellion. Led by Henry Joy McCracken and Samuel Orr, the United Irishmen of Antrim rose on June 6, but without the participation of the Defenders, its largely Catholic agrarian element. Undertaken almost solely by Presbyterian forces, the Ulster rising soon swept through Randalstown and Ballymena, with the rebels suffering severe losses in the process.

On June 9, a rebel force of over 7,000 under a Lisburn businessman, Henry Monroe, captured further important towns in the province. But the rebels were poorly organized and armed, and hampered by internecine quarrels and sectarian tensions, were defeated by superior government forces at Ballynahinch. McCracken, Monroe and many of the Ulster United Irishmen were executed and the rebellion faded after the declaration of a general amnesty.

But if the rebellion in the north and in north and central Leinster had failed, in the south the United Irishmen achieved significant successes. In wealthy County Wexford, considered according to historian Thomas Pakenham “a moral curiosity” in which “the Catholic peasantry were as peaceful and industrious as those of neighboring counties were lawless and disorderly,” and where “Protestant landlords were sometimes even popular,” the rebellion found its brutal and bloody apotheosis.

Under two Catholic priests, John Murphy and Michael Murphy, and armed mainly with pikes, pitchforks and customized farm implements, the rebels rose and destroyed the military garrison at Oulart on May 26, and quickly moved on to the strategic towns of Ferns and Gorey.

The rebellion spread quickly throughout the county. After ousting the garrison from Enniscorthy, the rebels used nearby Vinegar Hill as their base. Thousands of local volunteers joined the main rebel force, and the rebels moved south into Wexford town, where the formation of a pluralist republic, known as the Wexford Senate, had been announced.

Protected by a makeshift home guard managed by a retired British military governor, Matthew Keogh, the 500-member Senate initially hoped to become the impetus for a national government, but rebel defeats in north Leinster and elsewhere made it clear that the new republic would remain limited to the south-east of the country.

To the loyalist gentry of the town, it must have seemed as if they had been transported to revolutionary France or America, an impression not contradicted by a United Irishmen creed circulated in the embryo republic.

Question: What have you got in your hand?

Answer: A green bough

Question: Where did it first grow?

Answer: In America

Question: Where did it bud?

Answer: In France

Question: Where are you going to plant it?

Answer: In the crown of Great Britain Also published at the height of the rebellion, a Wexford catechism declared, “I believe in a revolution founded on the rights of man, in the natural and imprescriptible right of all Irish citizens to the land.” The new republic aimed to demolish the superiority of the privileged few who considered the people “an inferior and degraded mass, only made for their amusement or convenience, to dig, plow or enlist whatever the tyrant’s amusement.”

Under the leadership of Bagenal Harvey, a wealthy member of Wexford’s Protestant landed gentry, a rebel army attacked the port town of New Ross, gateway to Waterford and the west of Ireland. It was one of the bloodiest battles of the entire rising.

Poorly armed and barely trained in fighting, the rebels launched wave after wave of attacks on the army artillery, before finally retreating in the face of superior firepower. The loyalist forces went on a rampage through the town, looting and burning, and hanging and shooting suspected rebels without question.

Over two thousand died in the battle of New Ross. By the time the fighting ended, according to Thomas Pakenham, the area was filled with “the stench of two and a half thousand bodies under their pall of quicklime.” Outraged rebels retaliated with the massacre of more than a hundred prisoners, including women and children. Discouraged and disillusioned at his command’s lack of discipline and apparent blood-lust, Harvey resigned his post.

But although Wexford was completely under United Irish control, the end of the rebellion was already in sight. Large numbers of British troops began arriving in the country to reinforce the government’s harried army. Led by General Lake, the 10,000-strong force marched to the rebel stronghold at Vinegar Hill, burning and killing along the way. Those who escaped headed toward Wexford town, where news of the approaching army spurred one of the worst massacres of the entire rising: almost a hundred loyalist prisoners were murdered, viciously piked to death on Wexford bridge.

On June 21, Lake’s army attacked the rebel headquarters. Over 500 pikemen were cut down by cavalry charges and cannon fire on the Hill and in Enniscorthy town, and the soldiers celebrated by looting and burning, and by desecrating the corpses of the dead. A rebel hospital was burned to the ground, with the wounded still inside.

Meanwhile, another British General, John Moore, had marched towards Wexford from New Ross, brushing aside rebel stands along the way. Organized resistance collapsed in the face of better-armed and brutal attackers. When the new leader of the United Irish army, Father Philip Roche, arrived in Wexford to negotiate terms of surrender, he was captured, beaten and hanged.

Twenty-six days after the declaration of the Wexford republic, the surviving rebels fled, discarding their banners erablazoned with “Liberty and Equality.” Of the surviving United Irish leaders, those who were captured were quickly executed. Bagenal Harvey and Matthew Keogh, two of the most prominent Senate leaders, were killed and their heads displayed on spikes at the town’s courthouse.

Resistance was all but over, but pockets of rebels continued to hold out in the countryside for a few months. General Lake’s operations continued throughout the country, and brutal reprisals against suspected rebels were commonplace. In Carlow, over a hundred suspects were flogged, and fourteen more hanged. In Wexford, the occupying garrison killed and tortured hundreds more. Antrim and Down saw thirty `official’ hangings, and many more murders. By August, the country was quiet: the United Irish rebellion had been viciously quelled.

The Aftermath

Wolfe Tone and his fellow United Irish leaders had long hoped to persuade the French to intervene significantly in the Irish rebellion. But the death of General Lazare Hoche, leader of the unsuccessful Bantry expedition in 1796, and a champion of Irish independence, left the rebels without a strong influence in France, and Napoleon’s interest in the country had quickly waned. In August. a small force of 1,100 French landed at Killalla in Co. Mayo, under General Humbert, and after some initial successes at Castlebar and Ballina, were routed by vastly superior forces in Longford. The French troops were treated as prisoners of war. The United Irishmen who joined them were butchered in their hundreds.

Further reinforcements arrived from France on September 16, but it was too little, too late. The 200-odd soldiers landed at Rutland Island of Donegal, but sailed away again after hearing of Humbert’s defeat. A final expeditionary force of 3,000 was intercepted by the British navy in October: among those captured was Wolfe Tone, who was charged with treason and imprisoned. He did not deny the charges, declaring, “The great object of my life has been the independence of my country; for that I have sacrificed everything most dear to man.” He was sentenced to hang, but attempted suicide after his request to die by firing squad was denied. He only succeeded in wounding himself, however, and suffered in agony for a week before dying.

Photo: Wikipedia

Photo: Wikipedia

With the primary leaders gone, the movement faded. The immediate result of the rebellion was the Act of Union of 1801, which effectively brought Ireland into the United Kingdom and excluded the possibility of an independent Irish parliament. Sporadic disturbances continued however — another attempt at rebellion in 1803, led by Robert Emmet, younger brother of one of the 1798 leaders, was short-lived and unsuccessful -and the peasantry continued to pay a heavy price for suspected rebel sympathies.

Emigration off the land and into the factories and industrial towns of Britain began to increase, with up to 50,000 a year leaving Ireland even before the ravages of the Great Famine.

Of the surviving United Irish leaders, many also emigrated. Thomas Addis Emmet, among others, went to New York, where a small group of supporters had already gathered, and where anti-British opinion made him relatively welcome. Emmet went on to become State Attorney General; another leader, William McNevin, was appointed Resident Physician to the State of New York.

The Bicentenary

While their courage and idealism have made nationalist icons of rebels like Wolfe Tone, Edward Fitzgerald, Michael Dwyer and Fr. John Murphy, it should be remembered, particularly at a time in which Catholic and Protestant communities are cautiously inching towards reconciliation following the Good Friday Agreement, that fighting in the 1798 rebellion did not divide along standard sectarian lines. The factors which helped bring about the events of 1798 certainly included religious discrimination and sectarianism, but the rebellion was informed equally by French and American republicanism, and by a social and agrarian unrest that spanned, rather than played upon, religious divides.

And although Catholics did join the rebellion seeking emancipation and reform, it should also be remembered that there were many Catholics in the militia which quelled the revolt, and that the Catholic hierarchy generally opposed it.

Previous commemorations of the 1798 Rebellion, in 1898 and 1948, centered on the rebels as Catholic nationalists. But in the bicentenary year commemorations, which kicked off on New Year’s Day 1998 with an official opening at Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, displayed a broader scope. Included in the commemoration were concerts, exhibitions, and parades, many of which stressed the pluralist aspects of the rebellion.

It was an approach welcomed by many historians, including Tommy Graham, co-editor of History Ireland magazine. “The role I would see a commemoration having is to rediscover the inclusivity of the Rising,” he says. “The rebellion set the mold for modern Irish politics, but there has been a tendency to stress the Catholic, clericalist community in previous commemorations. I think it’s important to remember that 1798 had a more extensive, all-encompassing aspect too.”

Read also The United Irishmen and their American Legacy by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr

Colin Lacey is a former editor of Kerry’s Eye newspaper in Tralee, Co Kerry. He was a frequent contributor to Irish America and the Irish Voice, as well as other U.S. publications in the 1990s, when he lived in New York.

Fine work. The Presbyterian connection with US politics 1770s-1860s is

particularly interesting.

According to family tradition my DAUGHERTY ancestors were part of Robert Emmett’s rebellion and had to flee Ireland for their lives to America. Are there any lists with the names of those who participated in Robert Emmett’s rebellion? I know of three brothers; John, Edward and Manasseh Daugherty, along with John Black, James McGure and John Tait who were all alleged to have been in the rebellion of 1803.

Tim L. Daugherty

lyledaugh@aol.com

Dear mr. Daugherty

Would you have more names as far as i know there was a William Beck and his cousin William Beck, John Beck was killed.

Kind regards

Bobby Beck