On Monday, January 13, 2020, Phyllis McCready knew there was something wrong with the supply chain for the precious PPE frontline workers relied upon. McCready had been in this line of work for thirty years, ten at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center and twenty at Northwell. Through years of dealing with hundreds of different vendors of medical equipment and supplies—beds, ventilators, PPE, oxygen, syringes, etc.—she had developed a keen instinct. She knew the business inside and out; knew the companies she could rely upon to ship exactly what she wanted when she wanted it; and knew the companies to avoid. She knew how much equipment she needed in the Northwell warehouse and she knew how much of just about any supply she would need in the next week or month or year.

But on January 13 her world changed when her instinct told her there was a serious problem at the manufacturing end of the supply chain in China. On that Monday morning, McCready got word that there was something not quite right with an order from her largest supplier, Cardinal Health. Cardinal is an American-owned multinational health services company so central to the medical supply chain that 90 percent of US hospitals are customers.

Cardinal notified McCready that a shipment of surgical procedure packs from China had been compromised. Procedure packs are preassembled sets of sterile supplies such as syringes, surgical gowns, drapes, sponges, skin markers, suction catheters, and more, all needed for surgery. Having everything in one pack saves staff from having to collect a number of individual supplies. The representative from Cardinal told McCready that there was a problem specifically with the surgical gown in the pack. “He said that the surgical gown in the pack was compromised,” recalled McCready, “and I said, ‘Okay, since the pack is sterilized in the United States that’s not a problem. We can take the gown out of the pack and we can use everything else.’ And he said, ‘No, you can’t use the pack at all.’”

McCready pressed the representative from Cardinal, but he didn’t seem to have answers. He promised to get back to McCready with more information. A couple of hours later he called and told McCready that not only was there a problem with the gown, but that Cardinal was not going to be able to ship any of the packs that McCready had ordered at all. McCready pressed the representative again, but he had little information. To McCready, this was unthinkable. How could this possibly happen? The doctors and nurses at Northwell hospitals needed this equipment in order to care for patients. Cardinal’s representative told her that there was a “process problem” in the plant and that everything was on hold.

In all her years working in the field, McCready had never heard of a so-called process problem. After multiple calls with Cardinal’s upper management over the week, she still wasn’t getting any answers. “We never had a recall of this magnitude from a national company like Cardinal,” she said. “No notification. They just stopped shipping. It was strange to me, and I kept saying to my team, ‘Something is wrong.’ I even reached out to the FDA trying to get information about Cardinal packs and the recall, and I got none. This was a major recall; this was a nightmare. That day, I panicked,” she continued. “That was the first day in my career that I panicked. This is a major problem and not only for us, but for everyone.” McCready was well-prepared for almost anything—hurricane, flood, blackout, etc. But this was different. “I felt like I wasn’t ready,” she said. “I wasn’t prepared for this.”

It is no small irony that the products and supplies that would soon be desperately needed in the United States to protect clinicians from COVID-19 were actually manufactured in Wuhan, China, where it is believed the virus originated. In mid-January coronavirus alarms had not yet been sounded in the United States, but the process problem with that Cardinal shipment had McCready’s alarms ringing loudly. “That incident gave me a glimpse of what was happening in China,” she said. “The problem with Cardinal was very suspicious to me, because they never really told me what the issue was.” Evidently the gowns within the packs had been compromised in some way and the FDA would not permit release of the products. This was a very big deal in the US market and amplified McCready’s sense of alarm.

She instructed the staff to go out and buy as many Chinese-manufactured supplies as possible. She put in large orders for scrubs, gloves, bouffant caps, isolation gowns, shoe covers, procedural masks, disposable lab coats, face shields, and more. She called another major supplier, Medtronic, and said: “We need supplies and we need them now.”

Through the rest of January and into February, McCready and her team, working with Northwell’s Senior Vice President Donna Drummond, continued to focus on getting as much material from China as possible for fear of an imminent break in the supply chain. Not only were thousands of medical products manufactured there; many products manufactured elsewhere relied upon raw material produced in China.

The over-reliance on Chinese production for the medical supply chain came into sharp relief during the crisis. One of the major lessons we learned is that, going forward, we will need a more diverse and reliable series of suppliers from around the world, including stepped-up domestic production. American-made items will be far more expensive than Chinese-made goods, but the necessity for US based manufacturing could not be clearer.

But in January and February, McCready and Drummond were not yet thinking about creating a supply chain less reliant on China. They were focused on getting the PPE and other equipment that the clinical and support teams at Northwell would need. And as the weeks passed, it became clear to McCready that with the virus headed to New York, the need could be enormous. She bought gowns, face shields, and procedural masks by the millions. She purchased five times as many N95 masks as she normally ordered—more than she had ever ordered at one time. These were made by 3M in the United Kingdom, but she was concerned that the material supply line from China to the United Kingdom could be disrupted.

The news out of Italy was terrifying. McCready and Donna Drummond saw and read about frontline staff dying in some cases due to lack of protective gear. At Northwell we had a good base of supplies to begin with and that base was supplemented significantly by the orders the team had put in during the week of January 17. But now, in late February, as Italy was about to be inundated, the push was on to buy even more. By this point, however, every hospital in the country was in the market for more PPE and ventilators. We were competing with every major health system and every state government, as well as the federal government. It was madness.

As the marketplace of available equipment contracted, McCready found that the very large volumes she was accustomed to purchasing were unavailable. Swabs, used for taking a culture from a patient’s nasal passage, were running low, and McCready put in orders for three thousand, then five thousand. She got 2,500. On top of that, she was finding that shipments took longer than usual. Part of the issue was that suppliers were doing their best to get PPE to where it was most urgently needed, which at that time was Europe. When we at Northwell place a purchase order, the process of filling and shipping that order begins overseas. McCready told the team to continue placing orders even if they had open, unfilled orders for the same material. She was counting on the rule that as long as she had open orders, things had to ship.

The main vendors, Cardinal and 3M, were inundated with demands for supplies and equipment from across the world, but they were open with our teams and said honestly what they could and could not do.

And that is what we needed—transparency. If they assured us something was in the pipeline and on its way, it was true. Sometimes delivery dates shifted and were delayed, but we eventually got our orders filled.

In March the data was telling McCready and Drummond that usage of gowns, masks, and other equipment was starting to climb. This was the perfect storm McCready worried about: increased demand, reduced supply. “I knew we were going to have a problem,” she recalled. As the patient census climbed so, too, did the staff’s need for PPE. At one point in March the need for isolation gowns, for example, rose from an average of about 8,500 per day to more than fifty-five thousand per day. We went from using about 18,600 N95 masks a month to using about eight thousand per day—225,000 per month. This skyrocketing usage put tremendous pressure on Drummond, McCready, and their team to find new sources for N95 masks.

They called upon every vendor they could find to try and buy more. “We continued to receive the masks from 3M although not in the volume we were asking for,” said McCready. “And then word came from 3M that they could not deliver any more to us.”

One alternative was to order additional procedural masks, the thinner masks that prevent the wearer from spreading germs but do not protect the wearer from an airborne virus. A delivery of ten million procedural masks arrived in March, but there was a slight issue: The masks were being held at JFK and would not be released by the Port Authority. Fortunately, the appropriate officials found a way to enlist the support of the managers at JFK and the Teamsters to release the shipment.

The global marketplace for PPE and other equipment was a chaotic space. We received countless calls from people and companies claiming to have large supplies of N95 masks, as well as gowns and even ventilators. The problem with nearly every one of them was lack of transparency. Typically, with these cold calls, the contract would require that we place the payment—millions of dollars—into an escrow account. The stipulation was that when we signed the contract, the funds would be released to the seller from the account. But this left us with no guarantee of getting quality goods or any goods at all.

There were countless leads where somebody knew somebody whose friend had access to a large supply. None of these deals worked out. And even when we did receive much-needed ventilators from New York State, many arrived without parts needed to make them functional. At one point our staff members went to hardware stores to purchase garden hoses which they cut up and attached so vents would work.

In New York State, early projections suggested that ventilators might well be in short supply at the peak of the pandemic. We purchased four hundred new vents and although we did not end up receiving all of them, we always had sufficient quantities, in large measure because of our system’s ability to move equipment rapidly to wherever it was needed among our twenty-three hospitals. The state pitched in with two hundred and provided additional PPE, as well.

As we approached the peak, concern grew throughout the greater New York area about the possibility of not having enough ventilators for all the patients needing one. This was the stuff of our worst nightmares. Yes, we had a policy based on rigorous ethical, clinical, and legal analysis that would guide us in making a decision: Two patients, one ventilator—who gets it? While we had the policy, we certainly never wanted to use it and, fortunately, we never did. While we worked our sources to find ventilators, we also went to work trying to figure out whether there might be alternatives in an emergency. Some very clever scientists and engineers in our system came up with a viable alternative.

BiPAP machines are commonly used among people with sleep apnea to provide positive airway pressure (PAP) that helps them maintain a consistent breathing pattern at night. The machines are also commonly used with patients suffering from congestive heart failure or from chronic inflammatory lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In other words, like ventilators, these machines help patients breathe.

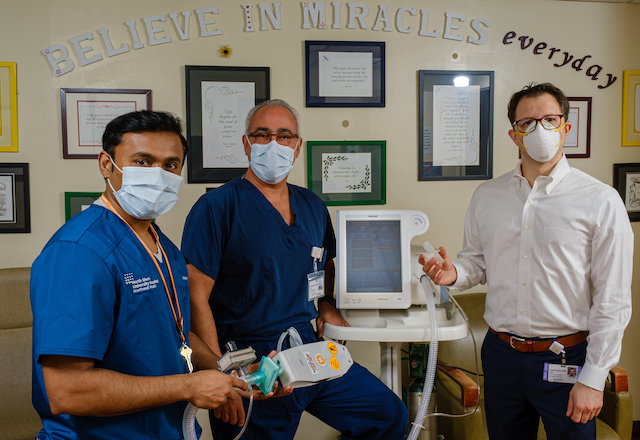

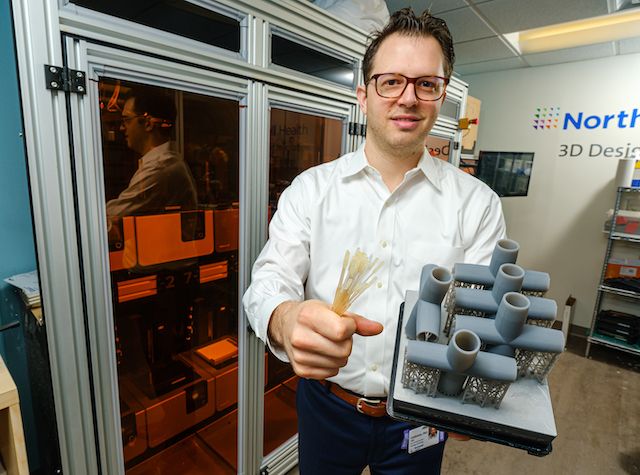

Dr. Hugh Cassiere, medical director for respiratory therapy services, and Stanley John, director of respiratory therapy at North Shore University Hospital, developed a method to convert a BiPAP into a pressure-controlled ventilator that could be used on patients with COVID-19 (or any other patients for that matter). But there was a catch: Their invention would not work without an essential part—a small, plastic, T-piece adapter.

And these were in short supply—so short that we were unable to get any. Enter Todd Goldstein, PhD, director of 3D design and innovation at Northwell. The three men collaborated to come up with a way to design a 3D-printed T-piece. They tested it successfully and set to producing dozens of the 3D-printed pieces so that they could convert BiPAP machines when the patient load was heaviest. In another bit of innovative magic, our team in collaboration with the University of South Florida and Formlabs, a 3D printing company, produced 3D-printed nasal swabs needed to test patients for the virus, swabs which were at that point in woefully short supply throughout the country.

One of the lessons Phyllis McCready takes from the COVID-19 experience is that she intends to be better prepared in understanding where everything is coming from. “I don’t just want to know where the manufacturing plants are making the products; I want to know the origin of the raw materials and the full path to completion of the product,” she said. The problem with ventilators, for example, was not that companies wouldn’t ramp up their production. Rather, they did not have the parts they needed in order to ramp up their production, because those parts were coming from China.

Donna Drummond observes that, in the future, prices for some items will rise because within our system we will insist upon buying some supplies manufactured in America. In fact, while the crisis was still going on in May, we were exploring the possibility of purchasing a PPE manufacturing company located in the United States so that we and others will have a steady supply of domestically made equipment and supplies in the future. And a major improvement Drummond envisions is an investment in automation to update our supply-chain systems “so that we have the information that we need more readily available to manage our supplies. We have to become more like Walmart in terms of automation—to know where the equipment is and who is using it at any given moment. Our goal needs to be a better understanding of the cost of care, including supplies, as well as the ability to better track them. This goes beyond emergency preparedness.”

Our supply team scoured the world for masks and other protective equipment, for ventilators, for swabs, for everything that every other major health system in the world was competing for, and they came up with the products to protect our staff and care for our patients. But this entire process needs a massive overhaul at the national and even international level. As many others have noted, the idea that our organization, other health-care systems, our nation, and the world rely upon China almost exclusively for the manufacture of these crucial items is a dangerous gamble. Domestic production of essential supplies is a matter of national security in the future.

Above is an abridged excerpt from Leading Through a Pandemic by Northwell President and CEO Michael Dowling and Charles Kenney.

Leading Through A Pandemic is available at Barnes and Noble and Amazon.

Return to the Salute to Northwell.

Leave a Reply