There’s as much of the old sod in the White House as there is on its south lawn.

The backgrounds of America’s First Families are diverse: Nancy Reagan and Lady Bird Johnson have Spanish forebears; Herbert Hoover was Swiss and Canadian; Mamie Eisenhower was part Swedish while Ike was German; Martin Van Buren and the Roosevelts were Dutch; James Garfield had a royal strain of French; Eliza Johnson’s parents were immigrant Scottish sandal-makers; both Calvin Coolidge and Edith Wilson had American Indian blood–she being a direct descendant of Pocahantas.

Yet it is the Irish American who represents the largest majority of those who have been President or First Lady.

President Bill Clinton’s Irish ancestry is through his maternal great-grandfather Levi Cassidy, and Barack Obama’s great-great-great grandfather was Falmouth Kearney from Moneygall, Co. Offaly has already been reported. They represent a long heritage at the White House.

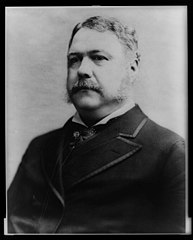

When Dutchman Franklin Delano Roosevelt told an uncomfortable audience of the Daughters of the American Revolution that “we are all immigrants,” he was not far off course regarding several of his predecessors’ parents. Seven presidents were first generation Americans, and three of them had parents who arrived directly from Ireland. James Buchanan’s father, James, was born in Ramelton, County Donegal and came to America thirty years before the president was born. Chester Arthur’s father, William, was born at The Draen (The Place of Thorns) near Ballymena, County Antrim. Arthur’s father’s birthplace was never a political issue, but the son’s was, for it was claimed, and never disproved, that the president was born on the Canadian side of the Vermont border, in direct violation of the law stating that presidents must be American-born only.

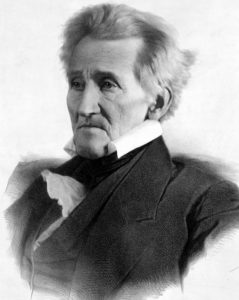

Both of Andrew Jackson’s parents came from Carrickfergus in County Antrim and arrived in the States just two years

before Jackson was born. The red-haired “Old Hickory” had a legendary temper that was particularly riled in his hatred for the British, which he displayed after a childhood during which a redcoat struck him and his brother with a sword.

Another Anglophobe was Welshman Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, several sources claim, also had Irish blood from Galway, but the true origins of his family, which immigrated first to the West Indies and then to Antigua before coming to Virginia, are not absolutely certain. It is interesting to note that on St. Patrick’s Day, 1802, during Jefferson’s presidency, the “Sons of Hibernia” marched in front of the White House, with shamrocks stuck in their hats.

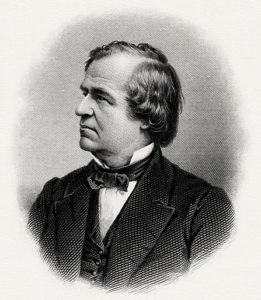

Andrew Johnson’s grandfather, also called Andrew, came from Mounthill, Larne, County Antrim. The 17th President, born, the son of a janitor, in Raleigh, North Carolina in 1808, married a shoemaker’s daughter who taught him to write.

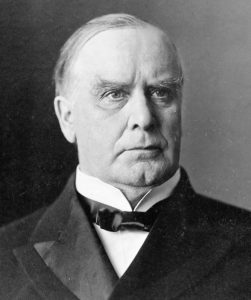

William McKinley was the great-great-grandson of James McKinley who emigrated from Conagher near Ballymoney, County Antrim, in about 1743.

William McKinley was the great-great-grandson of James McKinley who emigrated from Conagher near Ballymoney, County Antrim, in about 1743.

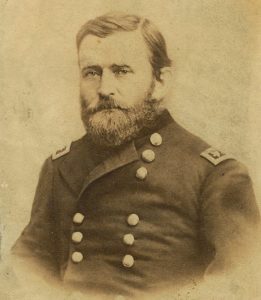

Ulysses Simpson Grant was the great-grandson of John Simpson who was born in 1738 at Dergina, near Dungannon, County Tyrone. Grant visited the North of Ireland in 1878.

Other Presidents were further removed from the old country. James Polk’s great-great-grandfather William was born in Donegal, Ireland, and his great-great-great-grandmother Magdalen Tasker was born in Moneen, near Strabane, County Tyrone.

Grover Cleveland’s Irish ancestry came through his mother, Anne Neal, whose father, Abner, came from County Antrim to America in the 18th century.

Benjamin Harrison’s mother, Elizabeth Irwin, was descended from two great-grandfathers from the province of Ulster: James Irwin and William McDowell, who emigrated in the early 1700s. Theodore Roosevelt’s mother, Martha Bulloch’s Huguenot ancestors, came from Larne in County Antrim.

Woodrow Wilson’s grandfather James, encouraged by his neighbor and friend John Dunlap who printed the Declaration of Independence, emigrated from Strabane, County Tyrone, in 1807. Dunlap wrote to James: “The young men of Ireland who wish to be free and happy should leave it and come here as quickly as possible. There is no place in the world where a man meets so rich a reward for conduct and industry as in America.”

Many of America’s most famous First Ladies boast Irish blood. Dolley Payne Madison’s mother, Mary Coles, was Irish. It was Dolley’s maternal grandfather William Coles who came to America from Enniscorthy, Ireland, and settled in Richmond, amassing a fortune. Widower President Chester Arthur’s sister, Mary McElroy, who served as his First Lady, was said to have derived positive attributes from her Irish blood. In 1888, one writer noted of Mary: “Like Mrs. Madison and Miss Lane [bachelor President James Buchanan’s niece and First Lady], she is of Irish and American blood, which so often produces beautiful women. She has the rare combination of very dark hair and eyes and a most delicate complexion. . .and high-bred airs.”

Eleanor Roosevelt, like her immediate predecessor Lou Hoover, was also Irish. Though her most prominent ancestor was Edward Livingston, who swore George Washington in as president, and was descended from very old colonial Dutch and English New York families, Eleanor’s maternal great-grandfather, Valentine Hall, was an Irish immigrant who settled in Brooklyn. His “remarkable business ability” in commercial trading afforded him the chance to buy large chunks of New York real estate, and he retired before he was fifty. Eleanor Roosevelt humorously recalled that when Hall’s son, her grandfather, needed money to finish his manse on the Hudson, he went to his mother, Mrs. Hall Sr., who “would go to the wardrobe and rummage around,” then come out “with a few thousand dollars.” Mrs. Roosevelt said this went back to her great-grandmother’s Irish immigrant habits, “because in Ireland it would be perfectly normal to keep your belongings in whatever was the most secret place in your little house. . .my great-grandmother evidently had carried [the habit] into the new world and proceeded to do so.”

Eleanor was married to her distant cousin Franklin Roosevelt on St. Patrick’s Day, 1905, her mother Anna Hall’s birthday. Eleanor’s uncle, President Theodore Roosevelt gave her away at the ceremony, being in New York because he was reviewing the St. Patrick’s Day Parade. Outside of the house where the Roosevelts were married, little boys waited to see the president, and carrying American and Irish flags, greeted the wedding guests. Later in the day, Teddy Roosevelt spoke before the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick at Delmonico’s restaurant. He told them, “American is not a matter of creed, or birthplace, or descent. That man is the best American who looks beyond the accidents of occupation or social condition, and hails each of his fellow citizens as his brother, asking nothing save that each shall treat the other on his own worth as a man…”

Bess Truman was angry when, as her daughter Margaret set sail for a tour of Europe including Ireland, rumors were revived that her grandfather, David Wallace, was an Irish immigrant. The first lady asked that Margaret hold a press conference in Dublin clearing up newspaper reports that the president’s daughter was going to be greeted by her Irish Wallace relatives when she arrived. “I want it settled, once and for all,” Mrs. Truman wrote her daughter. “The original Wallace family did come from Ireland in 1684. . . The current story is that I am the daughter of ‘Robert’ and that he still lives somewhere in Ireland. I’m sick and tired of it.”

Most think of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy as French, because of her father’s distinguished Gallic family and her own study of French culture and art. Through her late mother Janet Lee’s family, however, Jacqueline Kennedy is of Irish ancestry. James Thomas Lee, Jacqueline’s paternal grandfather, was the grandson of Irish immigrants who came to America at the same time the Kennedy and Fitzgerald families did, during the potato famine of the 1840’s. Lee worked his way through Columbia University where he earned his M.A. and law degree. After practicing as an attorney, he succeeded in real estate and was vice president of Chase Manhattan Bank, and later president of New York Central Savings Bank. His wife, Margaret Merritt, was also Irish, her parents immigrating to America a generation later than the Lees.

Her birthname was Thelma Catherine, but from the day she was born, the fiercely independent youth was known as Pat. Her father, Will Ryan, was the adventurous son of Irish Catholic immigrant parents from County Mayo. Copper miner Ryan, returning home to his miner’s shack in the mountains of east Nevada was so ecstatic that his daughter was born close to midnight on March 16, he decided “Pat’s” birthday would be celebrated on St. Patrick’s day. “Well,” he explained, “she was there in the morning, my St. Patrick’s babe in the morning.” It was after he died that she began officially calling herself Patricia, after Ireland’s patron saint. Her birthdate and ancestry even became a political issue when her husband delivered his famous Checkers speech in 1952. “I am not a quitter. And Pat’s not a quitter. After all, her name was Patricia Ryan, and she was born on St. Patrick’s Day, and you know the Irish never quit.”

But Pat Nixon, according to daughter Julie, never seemed comfortable being labeled Irish and German (her mother had immigrated from Germany). She thought of herself as an American. Though she was proud to be Irish and never denied it, the first lady was initially displeased to learn in 1971 that plans were underway for a scheduled reunion between her and Ryan relatives in County Mayo because it would smack of artificiality. There was trouble, however, in even locating her husband, President Richard Milhous Nixon’s Irish relatives.

The Nixon Irish family originated in Timahoe, and the president even named his Irish setter King Timahoe. Julie Eisenhower wrote of an American Embassy in Dublin report of “scouring the Irish countryside for distant cousins. . .” Richard Nixon’s mother Hannah was descended from the Milhous family, Irish Quakers from Kildare, Ireland, who came to William Penn’s Quaker colony of Pennsylvania. The original Nixon ancestor, James, came from Ireland to Delaware in 1731. After the quiet visit to Timahoe, President Nixon stopped the official motorcade along a quiet roadside, where he greeted curious Irishmen on horseback and took in the serene open land about him. As it turns out, however, the Ryan family reunion was the most memorable moment of the October trip.

In Ballinrobe, County Mayo, Pat Nixon had a friendly and private luncheon at Ashford Castle with thirty relatives, and was afforded an opportunity to speak personally with many of her cousins. Her daughter recalled one cousin in particular, John Fahey, 96, who took the First Lady through the ancient burial grounds of their family. With tears in his eyes over the meeting, Pat Nixon warmly embraced him with an arm around his shoulder. “You’re spry,” she said, “and mighty nice, Mr. Fahey.”

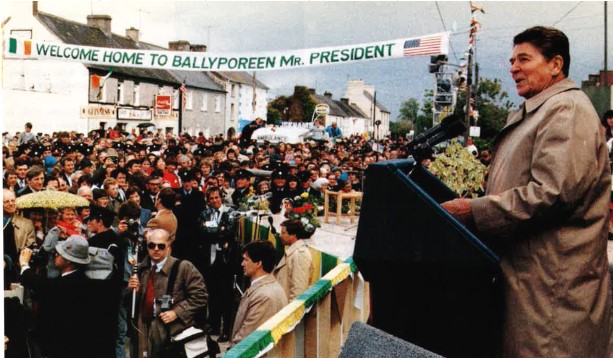

Ronald Reagan’s simple, two paragraph letter to Don Regan when the latter resigned as White House Chief of Staff on February 27, 1987 revealed his own proud ancestry. Reagan recalled the words of “our forefathers” by writing “may the sun shine warm upon your face, the wind be always at your back, and may God hold you in the hollow of His hand.” The forefathers Reagan referred to weren’t Mayflower pilgrims or pioneers crossing the Great Divide. They were Irishmen.

Reagan’s father Jack was a tall, black Irishman with a sardonic wit. A Democrat and a Catholic, he was a minority in the small town of Dixon, Illinois who defended the rights of minorities like blacks and Jews. His son Ronald, though raised a Protestant like his mother, inherited Jack’s ability to swap jokes and blessings. In June 1984, while attending the London Economic Summit, Reagan made a side trip to visit the town of Ballyporeen, Ireland, the home of his great-grandfather who came to America.

On his 1995 visit to Ireland, President Clinton, who has Irish ancestry through his maternal side, the Cassidys in Co. Fermanagh, in a speech at College Green in Dublin stated, “My mother was a Cassidy and how I wish she were alive to be here with me today. She would have loved the small towns and she would have loved Dublin. Most of all, she would have loved the fact that in Ireland, you have nearly 300 racing days a year. She loved the horses.

In a May, 2011, visit to Ireland, President Obama introduced himself to the crowd chanting his name by saying, “My name is Barack Obama, of the Moneygall Obamas, and I’ve come home to find the apostrophe we lost somewhere along the way.”

Of all the presidents, however, the one who most proudly celebrated his Irish heritage was John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

The Fitzgerald and Kennedy family saga from rags-to-riches, from poor potato famine immigrants to Boston politicians is perhaps the most famous of any presidential family. The Kennedys came from Dunganstown, County Wexford, and the first in America was Patrick, who arrived in Boston in 1848. The Fitzgeralds came from the same county, but had a longer and more distinguished history. They were originally Italian, and as the Gherardini family of Venice were awarded a castle and title by William the Conqueror for their help in the invasion of England. They immigrated from Italy to Ireland where the name was transformed. Centuries later, JFK quipped that he had never “had the courage to make that claim, but I will make it now, on Columbus Day in this state of New Jersey.”

Kennedy was the first president to make an unabashedly sentimental trip to the emerald land of his ancestors, in June of 1963. There, he had a simple lunch of salmon and tea with relatives in the home of his cousin, Mary Ryan, a matriarch who took control of the day. “You haven’t shown your face at this door for twenty years,” she pointedly told one visiting relative, “and now you’re horning in here because President Kennedy is coming!” The president laughed at all the uproar in the small town and assured his cousin, “we will come only once every ten years. . . Many people are under the impression that all the Kennedys are in Washington, but I am happy to see so many present who missed the boat.”

When he spoke before the Irish Parliament in Leinster House, he noted that some of its architectural features were said to be copied in the White House design by its Irish architect, James Hoban. “I have no doubt,” Kennedy wryly noted, “that he believed. . .he would make it more homelike for any President of Irish descent. It was a long wait, but I appreciate his efforts.” When he received honorary degrees from Ireland’s Catholic Trinity College and Protestant National University, he said he’d “cheer for Trinity and pray for National.” In Cork, he introduced the Irish born Monsignor O’Mahoney as “the pastor of a poor, humble flock in Palm Beach, Florida.” In his ancestral home, he joined a chorus of “We Are the Boys of Wexford,” prompted by a nun. In a Dublin castle, he joined a group of gathered girls in singing “Danny Boy.”

But Ireland seemed to give him a pensive and peaceful frame of mind after his grueling European tour. He softly repeated the writings, poetry, and lyrics of Gaelic writers. He quoted Shaw in saying, “Other people see things, and say why. But I dream things that never were, and I say, why not?” On his last night, President Kennedy repeated the lines of a famous song, before a hushed crowd.

“Come back to Erin, Mavoureen, Mavoureen, come back aroon to the land of my birth, come with the shamrock in the springtime, Mavoureen.” And continued, “This is not the land of my birth, but it is the land for which I hold the greatest affection, and I will certainly come back in the springtime.”

At Shannon Airport, before he departed, President Kennedy repeated another poem to a small gathered crowd. Then, before turning to board Air Force One, he told them his thoughts on leaving.

“Well, I am going to come back and see Old Shannon’s face again, and I am taking, as I go back to America, all of you with me.”

This story has been updated from an earlier version that ran in July/August issue, 1994.

Leave a Reply