Imagine no possessions

I wonder if you can

No need for greed or hunger

A brotherhood of man …

Wednesday, October 9, 2024 marks what would have been the 84th birthday of rock legend, John Lennon, a founder of the Beatles, and a singer, song-writer and social activist.

John was born in Liverpool in the north of England—a city sometimes referred to as the 33rd county of Ireland or East Dublin, because its Irish roots were so evident. True to form, John’s ancestors were Irish. His grandfather, James Lennon, had been born in Dublin in 1858. He, like so many of the post-Famine generation, emigrated to seek better prospects of employment. However, while the majority of these emigrants travelled to North America, James settled in Liverpool—usually the only option for those who could not afford to go further afield. Brought up by his Aunt Mimi, John never knew his Irish family, yet he identified strongly with that part of his heritage.

Early in the Beatle’s career, they played in Ireland: in Dublin and Belfast in November 1963, and again in Belfast a year later. On each occasion, fans queued all night to get a ticket to the show. A display of ‘Beatlemania’ which accompanied their time in Dublin, led to the Belfast police ‘bracing themselves;’ for similar scenes in the city. In what was known as ‘Operation Beatle’, extra police were on duty and crash barriers were erected. The Beatles were met at the border and taken by a secret route to Belfast. A curmudgeonly report of the Beatles’ first visit appeared in the regional paper, the Sligo Champion:

The Beatles have come and gone. During their short stay they collected—I estimate— some £2,000 from the teenagers of Dublin: were the cause a near-riot and much inconvenience to thousands of adult Dubliners. I sincerely hope that they never come again.

After Dublin they went to Belfast where in another two-show stand they collected about £2,000. This is not bad going for a group of young men.

The article concluded with an appeal to the government to “exclude the Beatles, the Cockroaches and the Bugs—whatever they call themselves—from Irish cinemas and Irish dance-halls.” Despite this heartfelt plea, in November 1964, the Beatles played in the King’s Hall in Belfast. Demand was so great to see them that a second show was organized. The success of the Fab Four resulted in many imitation bands springing up including “The Vipers,” who were described as Ireland’s answer to the Beatles.

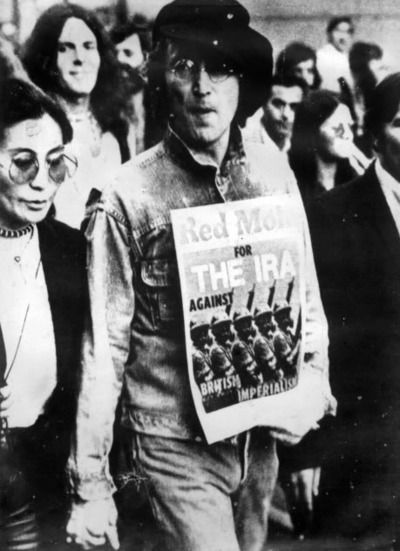

In the wake of “Bloody Sunday,” when 14 unarmed civil rights demonstrators in Derry were killed by the British Army (13 died on the day, one later), John (with his second wife Yoko) penned two songs “Luck of the Irish” and “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” which appeared on his Some Time in New York City album (1972).

Well it was Sunday Bloody Sunday

When they shot the people there

The cries of thirteen martyrs

Filled the free Derry air

Is there any one among you

Dare to blame it on the kids?

Not a soldier boy was bleeding

When they nailed the coffin lids!

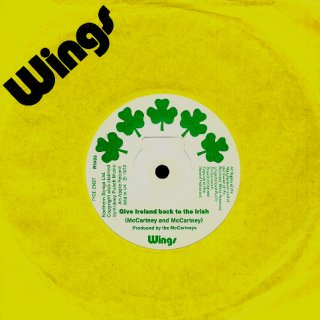

Paul McCartney, now estranged from John, who also had two Irish grandparents, also felt moved to respond to the events in Derry, penning only two days after Bloody Sunday, “Give Ireland back to the Irish”:

Great Britain, you are tremendous

And nobody knows like me

But really, what are you doin’

In the land across the sea?

Tell me, how would you like it

If on your way to work

You were stopped by Irish soldiers?

Would you lie down, do nothing

Would you give in or go berserk?

Both John and Paul’s songs were banned from broadcast in the United Kingdom by the BBC, by the popular Radio Luxembourg, and by other broadcasters and radio programs as far away as New Zealand. Advertising space could not be purchased on the grounds that the songs contained “political controversy.” The reaction of music critics to the songs was also largely negative, leading John to respond:

Here I am in New York and I hear about the 13 people shot dead in Ireland and I react immediately. And being what I am I react with a four-to-the-bar, with a guitar break in the middle … My songs are not there to be digested and pulled apart like the Mona Lisa. If people on the street think about it, that’s all there is to it.

Years later, however, John’s song was to inspire a Dublin band, U2, to compose their own song on this topic, Bono always insisting that their version was a song for peace: “Cause tonight, we can be as one, Tonight.”

From his home in New York, John continued to speak out in support of Irish independence and against police and army brutality in Northern Ireland. In March 1973, John was ordered by the U.S. immigration authorities to leave the United States and given 60 days to do so. The official reason given for his deportation was a conviction in England in 1968 for possessing marijuana. Not surprisingly given his high profile, at this stage, John was under secret surveillance by the FBI. It was not until 1976 that the order of deportation was overturned and John received a Green Card. In the previous year, John and Yoko had had a baby boy, Seán, whose birth marked the start of a more mellow phase in John’s life as a stay-at-home father. This period was brought to a brutal and abrupt end on 8 December 1980, when John was killed outside his home in New York. He was aged 40.

Photo: visitliverpool.com

In 1967, following the meteoritic success of the Beatles, John bought an island off the coast of Mayo—Dorinish Island in Clew Bay. He also applied to Mayo County Council for permission to build a home there. In an interview some years later, he was asked where he would like to be when he was 64—a reference to the Beatles’ whimsical song “When I’m 64.” John responded that he wanted to be living on his Irish island with Yoko. Tragically, he never got a chance to live that dream or to celebrate his 64th birthday. Nonetheless, John’s rich musical catalogue and his powerful vision of a better world based on peace, social justice, and love, live on.

This article is dedicated to Michael Kinealy (1955-2017) who loved John and loved Ireland. Sadly, he too, never got see his 64th birthday. On the day of this photograph, he had just been diagnosed with cancer and given six months to live. We spent a day together at our favorite places in Liverpool. It was a magical day. I didn’t want it to end. These statues are in remembrance of the Beatles’ final appearance in the city. They are by sculptor Andy Edwards who, coincidently, also created a statue of Frederick Douglass who I have written about. – C.K.

Christine Kinealy’s book Black Abolitionists in Ireland was published in 2020 by Routledge. It examines ten abolitionists – nine men and one woman –who visited Ireland between 1791 and 1860. Her other books include: Frederick Douglass and Ireland: In His Own Words (Vol. I & II), and several books on the Great Hunger including, This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52.

Christine Kinealy’s book Black Abolitionists in Ireland was published in 2020 by Routledge. It examines ten abolitionists – nine men and one woman –who visited Ireland between 1791 and 1860. Her other books include: Frederick Douglass and Ireland: In His Own Words (Vol. I & II), and several books on the Great Hunger including, This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52.

Great to revisit Lennon and Irish politics. The best!

wonderful.x.

Beautiful, Christine. I would expect nothing less from you, but still. A gorgeous piece of writing.