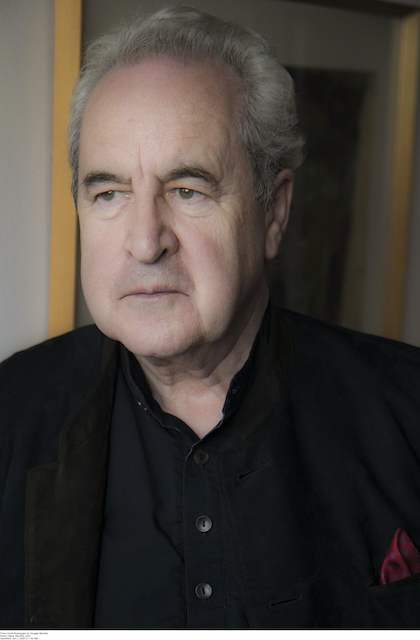

Will Real John Banville Please Stand Up!

Wexford native and Booker-prize-winner John Banville has spent his celebrated literary career exploring the slippery nature of identity and reality. Characters in Banville’s dazzling, challenging novels, such as The Untouchable or Athena, slip in and out of personas, and conceal so many secrets from friends and family (not to mention the reader) that they take the idea of the unreliable narrator to almost absurd lengths.

One of Banville’s most celebrated recent achievements – the trilogy made up of the novels Eclipse, Shroud and Ancient Light – revolve around Cass Cleave, a fitting name for an actor (!) who, well, cleaves his personality into many different identities, depending upon the role he is playing, or the person he happens to be talking to at a given moment.

No surprise, then, that John Banville – who turns 75 in December – is enduring a bit of an identity crisis himself. Back in 2007, Banville began writing Dublin thrillers set in the 1950s under the pen name Benjamin Black. Far more accessible than his challenging literary novels, mysteries like Christine Falls and Elegy for April introduced readers to a gloomy pathologist named Quirke. These were later turned into a BBC / RTE TV series starring Gabriel Byrne, and introduced Banville – well, Black – to a whole new set of readers.

Now, as Banville tells Irish America, Benjamin Black is dead!

It is just “John Banville” who now writes both artsy and mystery novels. Except in Spain, where apparently the Black books are so popular publishers don’t want to mess with a good thing.

Last year, in the novel The Secret Guests, Banville introduced readers to a new lead character – Inspector St. John Stafford. His latest mystery, just out in the U.S., is entitled Snow, and again features Stafford, as he reluctantly investigates the murder of a Catholic priest on a sprawling estate in a remote part of Wexford in 1957.

Banville talks to Tom Deignan about murder, TV, religion, and the difference between an Irish writer and an Irish writer.

Why did you want to do a second Inspector St. John Strafford book, following The Secret Guests?

I hope I won’t sound facetious if I answer by asking, why not? I rather like Strafford, and certainly find him far more sympathetic than the curmudgeonly Quirke. Though Quirke will be coming back, in a novel that will be published next year – another one? I hear you say. These books are carpentry, or better say cabinet-making, since they are, or try to be, works of craftsmanship. I leave the art stuff to Banville.

Any particular reason the latter was a Benjamin Black book and the new one a Banville?

The one coming out next year is a sequel to a previous BB caper. This required me to go back and read one or two BBs – a thing I would never dream of doing if it weren’t necessary – which to my surprise I found to be not bad at all. So I thought, why am I hiding behind a pseudonym? There’s nothing here too be coy about. So I killed off my dark brother Benjamin, except in Spanish-speaking countries, where he’s much too popular to die. People will of course be confused that the ever-pretentious Banville is writing crime novels, but I hope they’ll get used to it.

At one point – and why, do you think – did Snow become so important to this story that you wanted it to be a recurring image … and Joycean wisecrack … and give the book it’s title?

Honestly, no, JJ wasn’t at all in my mind. In fact, the original title was Snow Blind, but one of my editors suggested Snow instead, and she was right, it’s a good title. It doesn’t snow here any more, and I miss it, I suppose. And it seemed the create the right environment right for this very chilly plot.

Compare and contrast Inspector Strafford with your other main mystery man, Quirke? What do you like about each? How are they similar / different? Will we be revisiting Quirke (who gets a mention in Snow) any time soon?

Well, Strafford is a son of the Irish Protestant Ascendancy, a class, or caste, with which I have always been fascinated, especially as my roots are pure peasant. I like his diffidence, and the flashes of willfulness and menace he allows himself now and then. In next year’s book, April in Spain, Quirke and he figure equally. Quirke really is dour, isn’t he? Perhaps I should find a new lead character who is happily married with three adorable kiddies, lives in the suburbs, goes to Mass on Sundays, takes a dry sherry on Christmas day . . . What do you think?

On to the heavy stuff: In the past, you’ve said that you didn’t much consider yourself an “Irish writer.” Has that changed over the years?

But I do consider myself an Irish writer – but not an Irish writer, if you see what I mean. I was born here, I live here, I love the climate, couldn’t write anywhere else, and, most important of all, I write in Hiberno-English, that marvellous literary language invented by Swift, Burke, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats, Joyce, Bowen, Beckett, Iris Murdoch . . . I just don’t wish to play the ‘Irish card’, and wouldn’t be able to if I tried.

Your “literary” Banville books – rightly or wrongly – are considered more “serious”? Yet, it is primarily in your genre books that you have taken up seriously Irish questions, like the nation’s political growing pains (Secret Guests) and sins of the Church (Quirke books, Snow). Was there something about the mystery form that leant itself to such subject matter?

You know, George Yeats, WB’s wife, once remarked that Yeats’s Irish myth-making and political goings on were just a way of making poetry. Our dark history over the past hundred years is rich in violence, skullduggery, mischief and heartless abuse. I cannot think of a better setting for a crime novel than Dublin in the 1950s – all that rain and fog, all that drinking and clandestine whoring, all those nasty secrets hidden behind a cassock or a badly cut three-piece suit: what more could a crime writer ask for?

I’m fascinated by your past comparisons of Irish life under Catholicism to life in Europe under Communism. (From New York Times Book Review (2011): “[Ireland in the 50s] was a time of great secrecy. We were in the clutch of the Catholic Church. The church for us was what the Communist party was for Eastern Europe. We only discovered this when we got older, how unfree we were. And everything was hidden, as we have discovered, to our horror, in the past five or 10 years.?” Do you think Ireland can / will recover from this? What will it take? How long? Is something like a “truth commission” or other such body needed?

Yes, I was greatly struck when I first went to Eastern Europe before 1989 – the atmosphere in Budapest and Prague was exactly the same as that in Dublin. As to our dreadful history of abuse, we should have had a truth commission, of course we should, but we didn’t. When the scandals began to break we were too busy making money – phantom money, as we learned in 2008 – to give much attention to our inconvenient past sins. It seems to me the country is in much better shape now that the hysteria of the Celtic Tiger years has cooled and we have begun to accept at least some of the realities of life. The aim of Church and State in the past was to infantalise the population by means of brainwashing and spiritual terror – the Church – and by the nationalist fantasy of ‘A Nation Once again’ – the State. The journalist Fintan O’Toole came up with a wonderful acronym for how we see ourselves: MOPE (Most Oppressed People Ever). Maybe we’re moping less, and growing up a bit also.

Quirke inspired a BBC / RTE production starring Gabriel Byrne, and you’ve written movie screenplays. What do you like / dislike about the visual mediums as opposed to novels?

I love most movies and some television. What I would really like is to be a hack screenwriter of the 1940s, sweating over a typewriter in a one-bedroom bungalow in the Hollywood Hills, desperately scrambling to meet a deadline and turning out one-liners by the page, with a pint of rye by my elbow and a Camel stuck in the corner of my mouth . . . You get the picture. Since a child I have been screen-struck.

Any recent TV shows, in this so-called Golden Age of TV, that you have found particularly well-done?

I watched The Highwaymen recently and thought it excellent. Ozark is fine, but they should have stopped after the first series. I thought Bloodline superb – Cissy Spacek is astonishing in it – and wish they would make more. And of course I return frequently to The Sopranos, which is a work of art, though it should have had the nerve to depend less heavily on extreme violence. And Pawlikowski’s Ida is one of the few true cinema masterpieces since the war.

Who is a crime / mystery writer that you enjoy and perhaps others should take a look at?

Among the Americans, Richard Stark is matchless, as is Simenon, especially in the romans durs, though many of the Maigret novels are superb – at least for the first three quarters of the narrative, when Simenon suddenly remembers he has a plot to wind up, which he does any old how. I also think Pascal Garnier should be better known – his work is as black as your boot, and agonisingly funny. If you don’t know him, try How’s the Pain? A masterpiece – and crying out to be turned into a movie.

How have you managed during the coronavirus pandemic? What has it revealed to you about life or other related matters, great and / or small?

I’ve been in isolation for the past sixty years as a writer, so present circumstances are nothing new. Of course, a pandemic won’t teach us anything – the Spanish ‘flu killed scores of millions and was followed by the Roaring Twenties. Though I am somewhat surprised by the resilience of human beings. And there is this much to be said for Covid 19, it does give people something to talk about other than the bloody weather . . . ♣

Tom Deignan is an author, teacher, and columnist for the Irish Voice and Irish America (tdeignan.blogspot.com).

I’ve read all the Quirke books and am rereading Christine Falls after watching the Quirke TV series. Thanks for the excellent article! But no mention of the other “last name only” mystery solver – Morse. Interesting that Banville went back and reread the first few Quirke books. In the book Christine Falls Quirke is told by Sarah that Phoebe is his daughter when she is 20 years old where as much earlier in the other books and the TV show.