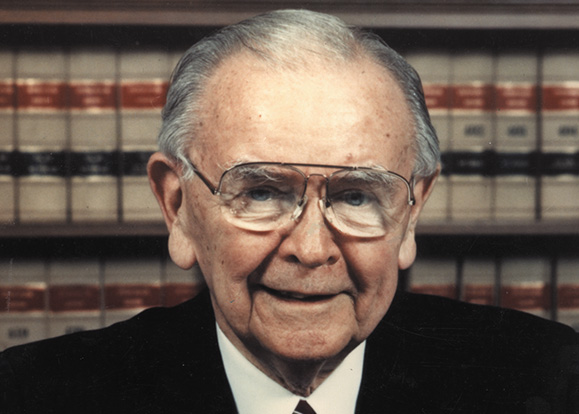

On April 25, 1990 William Joseph Brennan, Jr was 84 years old. An associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States for the past 33 years, he is considered – ruefully, by his many conservative detractors – to be one of the most influential shapers of public policy in the country.

A native of Newark, New Jersey, the son of Irish immigrants, Brennan was appointed to the the court by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1956; having served seven years on the New Jersey Superior and Supreme Court. Reportedly, Eisenhower, a Republican, subsequently regretted the appointment of both Brennan and Chief Justice Earl Warren as his two “mistakes.” Both turned out to be architects of the Supreme Courts progressive agenda, covering a slew of decisions on desegregation, sexual equality, obscenity, rights of the accused, church-state relations, liberal law, etc., aimed especially at broadening the provisions and safeguards of the First, Fourth, and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution.

In a New Yorker profile by Nat Hentoff, Burt Neuborne, a law professor at New York University, described Brennan as the most influential Justice of the Supreme Court since John Marshall (appointed to the court in 1801, and a champion of the principles of federalism). “Brennan knew how to blend his political instincts with a pervasive legal theory that transcended his personal views,” said Neuborne. “And he recognized the complexity if the task. That’s why he has been so much more influential than, for example, Hugo Black or William O. Douglas. While Douglas was alive, he was so vibrant a figure that his vividness tended to overshadow the staying power of his work. But when he retired, he left behind no legacy that transcended his death. By contrast, Brennan’s influence is so great because he worked out a theory of the Constitution that will endure beyond the work of Douglas, Black and many other justices.”

A practicing Catholic, Brennan, nonetheless, earned the scorn of many American Catholics—Irish Americans in particular—for his opinion on the School District of Abington Township, Pennsylvania v. Schempp (1963), which forbade school prayer in public schools, and Roe v. Wade (1973) which permitted legal abortions.

Towards the end of his career, Brennan found himself increasingly filing dissenting opinions in the Supreme Court, as the ideological balance has tilted dramatically to the conservative end of the spectrum, especially since the appointment by President Reagan of Justices Sandra Day O’Connor, Antonin Scalia, and Anthony Kennedy. Nonetheless, Justice Brennan retained an almost youthful enthusiasm for the court and vowed to stay there for as long as his health permitted.

He has also began to give more interviews, fueled, he said, by his desire to inform the public more about the way the court operates. He found it distressing that many of today’s young people didn’t even know the name of one justice, not to mention the nine, on the court.

Engaging and alert, when we met at his office in the nation’s capital, he showed a keen interest in his Irish roots, demonstrated by his recent membership in the Washington, D.C. chapter of the Roscommon Association. He visited Ireland twice, and considered attending a Roscommon clan reunion, except that his doctors forbade excess traveling.

Brennan was married for a second time in 1983 to Mary Fowler, following the death the previous year, after a long illness of his first wife, Marjorie Leonard. He and Marjorie had three children: William Joseph Brennan III, at the time of this interview, a trial lawyer in Princeton, New Jersey, (Justice Brennan told Nat Hentoff in the New Yorker that “in the coming election, we may be on different sides”). Hugh Leonard Brennan, then employed in the Department of Commerce, and Nancy Brennan Widman, then the director of Baltimore’s City Life Museums.

During an interview at his office in the Supreme Court, Brennan began by discussing his youth in Newark, and his parents, William Joseph and Agnes (nee McDermott) Brennan.

Sean O Murchu: Both your parents, William Joseph Brennan and Agnes McDermott were born in County Roscommon. Did they know one another before they came to the U.S.?

Justice Brennan: No, they did not. My dad was born and brought up in Frenchpark and my mother was born and brought up in Castlerea, Now, Castlerea and Frenchpark are only about 10 miles, if that much, apart, but they never met until they came to the states.

My mother came to the states to live with an aunt, a Mrs. Butler, who had a boarding house in Newark. My father had been working on building the canal at Trenton, didn’t like it very much, and had a chance to get a job in Newark shoveling coal at Ballantine’s Brewery. He needed a place to live and somebody told him about a Roscommon lady who had a boarding house. So he went down, applied and was accepted. My mother was about 17 or 18 at the time. That’s how she met him.

O Murchu: Was it that almost everyone in their families were emigrating at the time?

Brennan: I think so. Because, in fact, my father’s family consisted of two sisters, Catherine and Winifred, and two brothers, Patrick and Thomas, and they all – I don’t know what years, but shortly after my father – left, and in my mother’s family, her aunt was already here.

O Murchu: Did they have any work in Roscommon?

Brennan: You know how terrible things were there then? I would suppose, if there was any kind of work at all, they would have taken the chance. But they saw a chance for a better life in America. That’s what I think. I don’t know all the details because neither mother nor father talked about it much.

O Murchu: Did your parents have a strong feeling towards Ireland when they lived in Newark?

Brennan: Well, yes they did. But their memories were of hardships. They were reluctant to talk about it.

O Murchu: In past interviews you have attributed a lot of your success to your father? He obviously was quite successful, considering he immigrated to America and was elected to public office.

Brennan: He was very successful. Actually what happened is that when he started shoveling coal at Ballantine’s, he thought the conditions were bad for ordinary workers. He started organizing within Ballantine’s and then spread around to the other breweries around the city. Remember, there were no trade laws to help you in those days. You just has to fight your way through. He did it so well that he moved up within the organized labor hierarchy around Newark. At the same time he was going up locally, he was also going internationally in the International Brotherhood of Fireman and Oilers.

While things were moving ahead for him there was a trolley strike, locally and state-wide. There were trolley routes that went all the way down to the suburbs. Well, the transit company was headed by Thomas McCarter. The McCarters were the powerful family in Newark and in the state generally. One brother, Easel McCarter, was head of the largest bank in the state, the Fidelity Union Trust Company; Robert N. McCarter was the attorney general in the state and the senior partner in the leading law firm in the state. They really ran the state. They had a grip on the local police department in Newark, and the strike was defeated because the police were on the side of the McCarters.

Well that led to a movement in which my father was very active, to change the form of government in Newark. And before it was changed—in an effort to prevent change—my father was appointed a police commissioner by the mayor, and he promptly showed where he stood in the labor disputes and then that led to one fight after another. And, by God, they changed it. They changed the form of government from what was a mayor-alderman form to a mayor-councilman form, with commissions, and labor got representation. But that wasn’t enough for them. They swept away the whole government—councilman, mayor, alderman and all that business—and substituted it with a city commission of five, and each commissioner was assigned departments. The Department of Public Safety was in charge of the police, fireman, and licensing – the most powerful in the whole city. Well, they had a city election to elect the commissioners and first five were the elected commissioners. There were 80 candidates and my father finished third and was assigned the Department of Public Safety. The term was four years. He was third in 1917, he was second in 1921; and he was first in 1925 and 1929. And, by all odds, the most powerful public figure in the city in those days. He had a remarkable reputation, He died very suddenly of pneumonia in 1930.

Photo: Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

O Murchu: Did the family life change a lot from the time he was shoveling coal in Ballantine’s to when he was elected to the commission?

Brennan: Oh, my heaven, yes. It changed a lot. first of all there was now—it does not sound like much now—$5,000 a year. But there were eight of us. But yes, things were enormously better than they had been. And when I say, as I do indeed that I owe him so much in terms if values, I mean it. Even though there were eight of us, and he was on call 24 hours a day, he never neglected us.

O Murchu: Given your father’s success and motivation, did he imbue his children with the same sense of what one could achieve in the country?

Brennan: Oh, yes, with my dad, you had to be doing something all the time, working at something, preferably at something you liked. And I had every kind of job in the world. Across the street from us was a dairy farm and my brother Charlie, at five in the morning, would milk the cows and by the time they had cooled and bottled the milk, I would walk across the street and deliver it all the way up to the school, which was two miles away, and then in the afternoon I would deliver papers.

O Murchu: And you went to school at the same time?

Brennan: Oh, sure, and not only that but in the transit system, which was a trolley-car system, the fare was five cents and in rush hour there would be a mob running for a trolley car downtown. The transit company dreamed up the bright idea of having high-school kids carry a change purse and go up and down the trolley aisles with change so that there would be no delay in getting on. That paid $5 a week.

O Murchu: Paid in to the family?

Brennan: Oh, yes, indeed.

O Murchu: Was there a sense of being an Irish family when you were growing up in Newark?

Brennan: Oh, yes, I remember dad bought the family a player piano and I remember my mother’s favorite was John McCormack, the great singer, and there wasn’t anything of his that was recorded that we did not have the day it came out.

O Murchu: What kind of person was your mother then? Obviously your father was very dynamic?

Brennan: I wish I could do justice to her. Mother was just absolutely extraordinary, really, she was a sweet, caring woman, fending off my dad when he got upset with something we were doing. She would protect us.

O Murchu: She outlived your father?

Brennan: She did. Thank God she survived until my appointment here, I was here for about 10 years before she died.

O Murchu: Did she or your father ever return to Ireland?

Brennan: They went over in 1928. That happened to be my first year in Harvard Law School. You got your grades sometime in the summer and I remember how impossible it was to get telephone service in those days. My father sent telegrams saying, “Did you get your grades, did you get your grades?”

O Murchu: You have been there twice?

Brennan: Yes. The first time I was there, I met people who remembered my father and mother being there. They particularly remembered my father because he bought drinks for everybody in the pub.

O Murchu: How did you become attracted to the idea of a legal career?

Brennan: Well, in his position, my dad had a number of very close friends who were lawyers, and he was so taken with this whole bunch of Irish lawyers. They were the leaders of the bar and they were close friend’s of my fathers, and my dad encouraged me to do it and got them to encourage me. So I went to the University of Pennsylvania and then I went to Harvard Law School.

Photo: Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.

O Murchu: After you qualified, you used to speak at meetings of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick and other Irish organizations. How come you were interested in your Irish roots?

Brennan: My father kept me, all of us, well aware of not only the Friendly Sons but the Ancient Order of Hibernians. He used to subscribe to the Irish World and some others. And St. Patrick’s Day was a big holiday for us.

O Murchu: Have you managed to impart any of this sense of Irishness to your own children?

Brennan: I don’t think so. It’s been interesting. We Irish are not the only ones who are having this experience. Italians will tell you, the Poles will tell you, the old Poles, the old Irish, Back when I was growing up there were any number of Irish associations, and Irish affairs that my mother and dad used to go to all the time. I don’t think there are things like that now.

And you know, the thing that disgusts me—there are so many Irish who would rather not claim it [being Irish]. I resent it, I just think it’s so sad.

O Murchu: That applies to nearly every ethnic group in America. The way in which some people prefer to forget their history.

Brennan: And I certainly am not surprised at this, but I run into many from generations after mine who know damn little about their roots.

O Murchu: When you were appointed by President Eisenhower in 1956, it was stated, among others things, that you were filling the “Catholic seat” in the Court. That there is a “Catholic seat”and a “Jewish seat” on the Supreme Court.

Brennan: There used to be, but I think that it’s now overstated frankly. I have been told that President Eisenhower personally had two [criteria]: He would not appoint anyone who was not already a sitting judge in some court. I was the only appointee from a state court at that time. We’ve had Justice O’Connor since, who was appointed from a state court.

I have seen the record that President Eisenhower, when this vacancy arose, gave instructions to the Attorney General that he would like consideration of a Catholic. Not because there was a “Catholic seat” but because he was a close friend of Cardinal Spellman and Cardinal Spellman had suggested something like that. When I was appointed I was not the only one considered. There were others, who were non-Catholic, who were also considered.

O Murchu: So when you were appointed, were you aware that it was viewed as an effort to fill a Catholic seat?

Brennan: Well, I had heard that, but it went right over my head.

O Murchu: Subsequently, it has been reported that President Eisenhower regret ted your appointment.

Brennan: Well, I hope that’s not true. He certainly never said so to me. I have heard it said that he thought that both Chief Justice Warren and I were his mistakes. But, as far as I know, that’s just a story.

O Murchu: You have said before that, because of your Catholic background, one of the most difficult decisions you had to write was the Schempp decision in 1963 [a concurring opinion on the issue of school prayer].

Brennan: There was no question that there were unfortunate suggestions that on issues in which the church were interested in, I would be favorable to the church.

I was asked about this when my appointment was up for confirmation before the Senate Senate Committee on the Judiciary. A representative of a Protestant organization asked whether, in effect, “Where there was a conflict between your faith and the Constitution, who’s your boss, the Constitution or the Pope?” And the chairman of the committee, Senator [James O.] Eastland of Mississippi, didn’t think that it was an appropriate question. At least, he thought that it should be weighed by a subcommittee of the judiciary committee, which would report back to the full committee on whether they thought that it was a proper question. And so the next morning, the committee re ported that it was an outrageous question, saying, “You don’t simply ask anybody a question like that and we strongly recommend that the question not be asked.” So then Senator [Joseph C.] O’Mahoney of Wyoming said, “Mr. Chairman, I would like to ask the justice a question” – I was already sitting on the court as a recess appointee – “I would like to ask the justice a personal question and I am quite sure you will understand why I ask it.” So he said, “Mr. Justice, if a case presents a conflict between the Church and the Constitution, who prevails, the Constitution or the Pope?”

Everybody looked at him, but a senator is entitled to ask any damn question he wants. And he was the chairman incidentally of the subcommittee that had decided on the other question! So I said, “Senator, I took my oath to support and defend the Constitution just as faithfully and sincerely as you took the same oath when you were sworn in as a senator and, of course, the Constitution is what I’m here to interpret and the Constitution, obviously, is what I will interpret, no matter what kind of effect it may have on anything.“

That created a stir. A Catholic publication in Brooklyn demanded that I be strung from the nearest flagpole. Well, at that time the Archbishop of Washington was Archbishop O’Boyle – he wasn‘t yet a cardinal – and he had a young assistant, who‘s now the Archbishop of New Orleans [Archbishop Phillip Hannan], come over to see me. He said, “Now look, the Register, our local Catholic paper, will take care of that,” and they backed me up solidly.

O Murchu: Since then, the issue of a Catholic’s loyalties while in public office has arisen again in the U.S. It occurred in 1960, when President Kennedy was running for office, and even more recently, the bishop in San Diego forbade a local legislator to receive the Holy Sacrament because of her position on abortion. Are those kinds of pressures still exerted?

Brennan: Mine was in 1957. Since then you’ve had Justice Scalia and Justice Kennedy and me – you have three out of the nine who are Catholic – so you see what has happened to that. It’s gone. The bishop in San Diego was well within his authority, I know, but I think that was a very unfortunate thing for him to do. And I gather that more of the hierarchy agree with me than agree with him. And that’s something.

O Murchu: Also recently, Bishop Vaughan in upstate New York warned Governor Cuomo that he could end up in hell because of his support for federal funding of abortion. It’s been a tune that’s been played over a long period of time.

Brennan: It doesn’t look that it’s going to get as much attention anymore, after three of us being on the court and not a whisper from anybody.

O Murchu: But then Justice Kennedy and Justice Scalia are perceived as being conservatives, with whom the church would agree on matters such as abortion and school prayer. You are the person that they have to keep an eye on.

Brennan: I think they’d better be careful. They’d better be careful because justices get here and they can change.

O Murchu: That has happened in the past when justices have come here turned out to be different than people expected them to be

Brennan: It certainly has.

O Murchu: Judging from the correspondence our magazine gets, Irish Americans have a very strong reaction towards legislators and justices who support Roe v. Wade. I imagine you are constantly reminded of that with letters and the like.

Brennan: Oh yes. There used to be a flood, thousands, now it’s still maybe a dozen a week. I never even see them. The flood, or something like it, will start again as we get closer to the end of’ term and they await our decision on the Minnesota case.

O Murchu: In 1973, did you envisage that the Roe v. Wade controversy would last 17 years.

Brennan: Oh, no. I had no idea. I knew that there would be an initial reaction, but I didn’t anticipate it.

O Murchu: Not very long ago, your presence at a college graduation in Kentucky enraged the local clergy and you had to turn down an invitation to attend to accept an honorary degree. What happened?

Brennan: Oh, yes. My wife’s sister was president there for years and they offered me an honorary degree and I was glad to accept. And the biggest fuss began in Kentucky and I had letters from the governor and from others telling me how sorry they were that anything like this could happen. That was it. I wasn’t going to make it more difficult for the school or myself.

O Murchu: Do you ever feel inclined to point out that the freedom people have to attack you and your presence at the graduation ceremony in Kentucky or anywhere else is the freedom which you have been strongly defending all your life.

Brennan: Oh yes, I feel very strongly about that. I think that the most important provision of our Constitution is the First Amendment. It defines for us the kind of society we are and that we want to be. No matter what the criticism, I will never deny any citizen the right to say what he feels.

O Murchu: You mentioned that there are now three Catholic justices in the Supreme Court. Nonetheless; it’s still eight men and one woman and many would suggest that it no longer represents the ethnic diversity of the 250 million people in the United States today.

Brennan: I think that it’s terribly useful that there be diversity in the membership of the court, by locality – initially, seats on the court were reserved for particular sections of the country – and that kind of diversity is useful. All kinds of points of view should be represented in the court on major issues. And they are all major is sues. It’s hard to have a minor issue since we take about 150 to 160 a year out of 4500 that we are asked to review. It’s useful to have the broadest possible range of views

O Murchu: From a racial point of view, there are eight white members and one black member of the court. But, for example, there is now a large Hispanic population in the country, as distinct from 30 to 40 years ago. The ethnic mix of the country has changed dramatically.

Brennan: Certainly. Don’t forget that the size of the Italian population of this country is almost the size of the Irish and the Italians have always insisted for years that the Italians were entitled to representation. Until Scalia was appointed, they didn’t have it.

O Murchu: Do you see the composition changing further?

Brennan: Frankly, I think that it’s impossible to know. The guy who can give us the answer is the President of the United States, when he gets a vacancy. Remember, Carter served four years without a single vacancy. He didn’t make a single appointment.

O Murchu: From surveys carried out among high school kids in the U.S., it’s apparent that young people have a poor grasp not only of how the Supreme Court operates but of how the Congress and the Presidency work and how they relate to one another. Is that something that concerns you?

Brennan: I make speeches quite frequently on this subject. I addressed a joint meeting of the school of education and the law school at the University of Pennsylvania just a couple of years ago. And my whole theme was that the responsibility for curriculum is not the students’, who can not make up their own curriculum, but the teachers’ and the administrators’. It’s shameful that we get the kind of reports we do, of answers given by kids when asked about the Supreme Court. None of them can mention the name of any of us. I can’t imagine anything more important in our kind of society, and high school is the place to do it. Thank heaven, more of our schools are doing it.

O Murchu: Would it help the problem if people could see the court in session on television when decisions are handed down?

Brennan: I would love it. I’m the only one presently of the nine who would allow television broadcasts of our actual proceedings. There are arguments, that I respect, why we ought not do it – partly because of the significance of so many of our cases is so great to our society that there ought not be intervention of things that might distract the focus. I appreciate them. I think that those are problems that can be resolved. I am convinced that the day is bound to come when we will be televised.

O Murchu: Given that you have been involved in some of the most significant decisions in the court in relation to racial segregation-such as Cooper v. Aaron, which you wrote in 1958 – do you look now at cities such as your hometown like Newark or herein Washington D.C., where many argue, two societies, divided along racial lines exist. Is that something that is now out of the court’s hands?

Brennan: It’s out of our hands in the sense that we can’t innovate anything of our own. The only cases that we may decide are cases that come to us –cases and controversies as defined by Article Three of the Constitution. I think we made progress, perhaps, but we have much, much further to go. And one of the things that is distressing, I must say, is the indication that, as you just put it, bigotry is rampant in many, many sections of the country and that we are blocked in going forward. Nobody is more upset about all this than my colleague, Justice [Thurgood] Marshall, because he, more than any other single human being, brought about Brown v. the Board of Education. And to see the sorts of things that are still going on, sometimes he can’t help himself, and he’ll express himself in his opinions. Maybe it is an intractable problem , remnants of which we will always have with us.

O Murchu: In the past 10 years, you have tended to write far more dissents than in your first 15 years or so here. Do you ever feel that a lot of the work you’ve done is now being undone?

Brennan: No. Getting back to what we were saying about the First Amendment earlier, diversity of views is so essential in our scheme of things. There are vacancies, and presidents have appointed justices with whom I’ve been on the closest of terms, and had the best of relationships. I have sat with 22 other justices in my 33 years and I’ve never had a cross word with anyone. Of course we’re going to differ. Back in 1963 or 64, I’ve forgotten the year, I had a term when I didn’t write a single dissent, not one. I expect this year I’ll have 15to 20 dissents, something like that. But you have to remember that what’s expected of a member of this court, is the issue. Colleagues, and the majority of them, may differ with [the Justice], but he has a responsibility to keep saying what he thinks about the issue, even though he has to repeat himself after he’s been turned down, as I have by colleagues on my view that the death penalty is unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. Don’t forget Plessey & Ferguson, separate but equal, was the law of the land for some 70 years before it was overruled in Brown v. Board of Education. Things can change. I’m not too often in the majority on the major issues of the day, but it can all change again.

O Murchu: You mentioned that the only person who can decide the make-up of the court is the sitting president. Vacancies arose during President Reagan’s terms and now you have his hand-picked successor, President Bush, in the White House, a younger man who is in for four years, maybe longer. Does that make you feel that the opinions you have expressed in dissents will not be in the majority for some time?

Brennan: No. I accept totally what happens, but I don’t make any guesses as to what the outcome of a single case is going to be, because you never know until you’ve done it.

O Murchu: When you accepted an appointment to the New Jersey Superior Court in 1949, one of the reasons you gave for your decision was that private practice did not allow you to spend enough time with your family. Do you think that now, aged 84, that it’s time to relax and maybe retire? Is that a consideration?

Brennan: No, retirement for me is no consideration. I would not know what to do with myself that would give me what I get and the satisfaction I get here staying in the court. I was 84 last week – I can’t expect that there are many more years left in me and when the good Lord tells me that I’m not up to it any longer and I had better turn in my records, then I’ll be ready.

O Murchu: On doctor’s orders, you can’t travel much any more. You work basically in the court, go home and that’s it. Could one say that you ‘re a crusader in that you‘re determined to hang on as long as possible in the court?

Brennan: To be very candid, I suppose the answer has to be that I so love what I’m doing here, that I don’t want to stop doing it until I absolutely have to.

O Murchu: Do you feel that you’re doing important work here still?

Brennan: I do indeed, and even though many of my positions are now dissenting positions I still think that they ought to be expressed.

This interview by Sean O Murchu originally appeared in the June 1990 edition of Irish America.

If only we had this dedication to our Country today in our Courts. Irish heritage a brilliant & courageous one,Judge Brennan.