This story first appeared in Irish America in the summer of 1996 as the games of the Games of the XXVI Olympiad began.

John Brendan Kelly, father of Princess grace of Monaco, won two Olympic Gold medals in 1920 and one in 1924, competing in a sport which was the reserve of gentlemen, the single and double sculls. He remains the only American ever to win the Gold in single sculls. Kelly came from a family of achievers, whose story is embedded in Irish America. His daughter, Grace Kelly, became the world’s princess, but John`Jack’ Kelly was a star in his own right.

As the Olympic games open in Atlanta and people from all nations march into the stadium, the uniqueness of this event, where individuals can bring glory to their country through personal achievement, is celebrated.

For many Irish Americans, particularly in the early years of the century when Ireland was deprived of her own national identity, Olympic victory meant honor not just for themselves and the United States, but for the Irish people everywhere. No one accomplished that aim with more panache than Jack Kelly.

Photo: Wikipedia

Kelly has his own artistic embodiment — a monumental statue on the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, his home. He rows in bronze now, just below the Falls, the mill neighborhood where he grew up. The avenue is named for him, and to stand on Kelly Drive and look up at Jack pulling the oars with the strongly muscled arms and back that both built the city and conquered the world’s most elitist sport is to marvel at the sweep of Irish American history and the larger-than-life figures it produces. The base of the statue commemorates John B. Kelly’s Olympic achievements: the Gold Medal in the single sculls and the Gold in double sculls with partner Paul Costello, his cousin, in 1920, and the Gold again for the pair in 1924. Kelly remains the only American ever to win the Gold in single sculls.

But the story behind those medals contains all the elements of the classic journey made by the Irish in America, with some details appearing almost too good to be true.

First came the father of the Clan, John Henry Kelly, who arrived from the west part of County Mayo at age 17 in 1869. He worked on the railroads, married Mary Anne Costello, 17, also born in Ireland, and in 1876 moved to Midvale Avenue in the East Falls area overlooking the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia. There the ten Kelly children grew up in the shadow of Dobson’s Mill, the carpet and woolen factory where the Irish children of the Falls went to work at age nine or ten. The Yorkshire brothers who owned the mill made their fortune supplying blankets to the Union army. The hours: 6:30a.m. to 6:00p.m.. The wages and the conditions were Dickensian, but the communal spirit of the neighborhood that centered around St. Bridgid’s Church supported the ambitions of the next generation.

Photo: Wikipedia

Mary Kelly was a reader and instilled a love of literature in her children. Though they had to leave school early to work at Dobson’s, they read, and that, goes the Falls legend, made all the difference. One brother, George, born in 1887, became a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, and another, Walter, born in 1873, one of the most successful vaudevillians of his time. The oldest son, Patrick, began a construction company with his brother Charles. Here John Brendan “Jack” Kelly began the labor that would someday keep him from competing in rowing’s most prestigious event, the Henley Regatta. His exclusion would shock Philadelphia, where rowing “was more blue collar than blue blood,” says J.B. Kelly, Jack’s grandson and namesake. “I don’t know who came up to the Falls to recruit the Irish immigrant kids as oarsmen, but someone did and rowing became a working-class sport.”

J.B., who captained the rowing team at Harvard, says that Philadelphia’s attitude contrasted with the elitist image the sport had in New England. But it was in England itself where rowing was most identified with the upper class. Prince Albert sponsored the Henley Regatta, where winning the Diamond Sculls became the greatest challenge in the sport.

Jack Kelly was the American champion, but when he applied to race at Henley, the committee refused to allow him to participate. Kelly was not a gentleman, he worked with his hands, and his club, Vespers, had raised the money to send him in a way that did not conform to the rules. The reasons given were many. Still, for the people of the Falls, this seemed part of the pattern of discrimination that dogged them from famine-stricken Ireland to Dobson’s Mills. But the match that could not take place in England happened in the 1920 Olympics in Belgium. Jack Kelly defeated Jack Berdsford, the Henley champion, by one second — 7:35 to 7:36. “Those eight minutes of the single scull are the most demanding one could imagine,” says Chris Le Vine, nephew of Jack Kelly and an oarsman who rowed in the Hong Kong Dragon boat races and is president of a group restoring the historic Boathouse Row. Both he and his cousin J.B. Kelly agree that the aerobic demands of rowing, where the muscles of the arms, legs and back must all perform, require intense and constant training. Jack Kelly trained while working first for his brother and then in his own company, Kelly Brickworks, making his Olympic triumph even more impressive. To be sure the British understood the implications of his feat, Kelly sent the green racing cap he always wore to King George II.

But it was his son, John Brendan Kelly, Jr., who sweetened the victory for his father. “Kell” was four times a member of the U.S. Olympic team and the winner of the Bronze Medal in 1956. In 1946, he competed in the Diamond Sculls single at Henley. He did not win, but went back the next year to triumph. He came in first again in 1949. In less than 30 years the Falls was avenged.

Today Jack Kelly rows in bronze, but it’s the flesh-and-blood legacy that would most please both father and son. Pull off Kelly Drive and park at Vespers or Penn A.C. or any of the boathouses and you’ll meet tomorrow’s Olympians stroking toward their own championship season. Most come from the city’s Catholic high schools. The young men from St. Joseph’s are there practicing. Jay O’Donovan, John Rafferty, Patrick Gallagher, James Mannion, Clete Schwegmann and Tim Slezlendzielewski are ready to go. Three graduates of their school may row in this year’s Olympics.

In the boathouse, a picture of men who could be their grandfathers — James F. Dempsey, J.S. Flannagan and M.D. Gleason — shows them winning the Gold in the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis as a crew. Their confident descendants would not even begin to comprehend the barriers their ancestors shattered. That’s the real victory.

Oh, St. Joe’s just came back from a junior competition. They rowed against Eaton in the semifinals of the Henley Regatta. They did not win, but the future is theirs. John B. Kelly’s grandson, Prince Albert of Monaco, is on the International Olympic Committee and competes himself as a world-class skier. His cousins, Chris and J.B., guarantee that when this generation of Philadelphia rowers is ready to meet the challenge there will be plenty of Kellys to cheer them on to victory. ♣

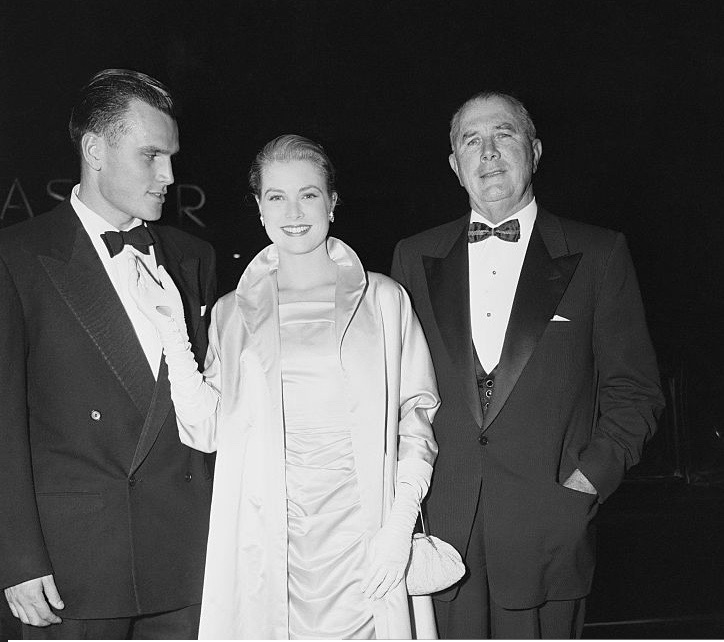

Photo: Hollywoodland Photos.

Read A Celebration of Grace Kelly by Mary Pat Kelly.

Mary Pat Kelly’s celebrated historical fiction series, the bestseller Galway Bay, Of Irish Blood and now Irish Above All tells the Irish American story through her own family’s saga. https://marypatkelly.

Great story Mary Pat !