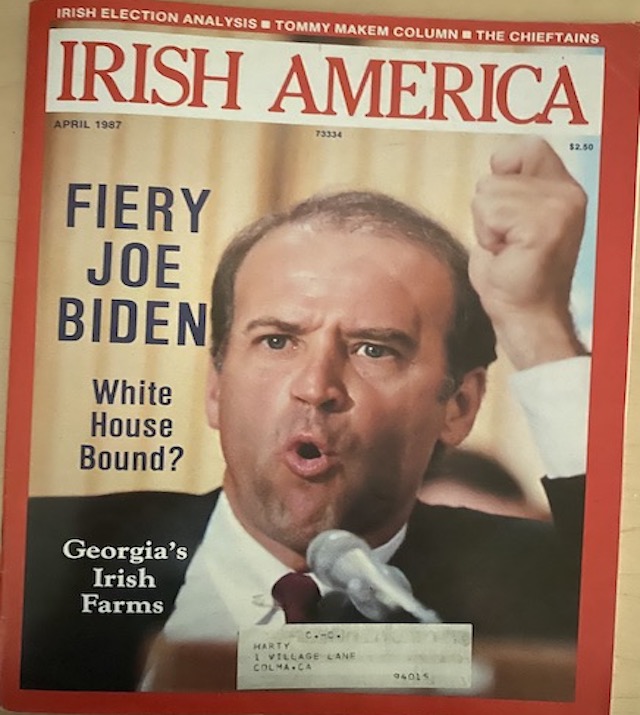

An 1987 interview with the then U.S. Senator from Delaware, now presidential hopeful

Joe Biden gave his first ever interview to an Irish publication in April, 1987 when he talked to Niall O’Dowd and revealed, for the first time in print, his passion for his Irish heritage, the story of his extraordinary Irish Catholic family, and his ambition, even back in 1987, to run for the White House.

We are pleased to bring you that interview, from Irish America’s archives, in its entirety.

April, 1987: Senator Joseph Finnegan-Biden, head of the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee, is one of a handful of people who can realistically aspire to the presidency of the United States.

While he is still regarded as an outsider for the 1988 Democratic nomination, there is unanimous agreement that the withdrawal of New York Governor Mario Cuomo has greatly boosted the chances of the 44-year old senator from Delaware.

He can certainly now claim the title of best orator of any of the 1988 candidates of either party. Those who have witnessed his impassioned addresses, either in the senate or on the stump can vouch for their fiery quality. Just last month he was in spectacular form at the AFL/CIO convention in Florida, winning a standing ovation from the delegates and an admission by the New York Times that he stole the show from the other presidential hopefuls present.

In addition to his own undeniable political attributes, he has assembled a superb campaign staff to prepare for the grueling trek ahead, including Pat Caddell, Jimmy Carter’s guru, who has switched from supporting Gary Hart, and Tom Donilon, widely regarded as an ingenious political strategist.

What’s more, the experts rate him as having a definite chance. Robert Boyd of the Knight-Ridder newspaper group says that Biden “could well be the Gary Hart of 1988.” Peter Hart, the Democratic Party’s main pollster predicts, “Before the end of 1987, Biden will be in the first-tier of Democratic candidates seeking the nomination.”

Biden’s national political career has certainly come full circle since its tragic beginnings. In 1972, when aged 29, just a few weeks into his first term as Junior Senator from Delaware, Biden’s first wife and baby daughter were killed in a car crash and his two sons seriously injured. He almost quit politics and was only coaxed back from the brink by family and friends.

The fact, that most of the family – and friends were Irish was an inevitable consequence of growing up in one of the most Irish Catholic cities in the United States, Scranton, Pennsylvania once home of the Molly Maguire’s, one of the most famous secret Irish societies of all time.

Biden has never forgotten those Irish roots, as this interview eloquently testifies. In that sense he is not dissimilar from another famous Irish American, Cardinal John O’Connor of New York who also hails from the same area and bears the same imprinting and pride in his heritage.

During our interview, which was extended by over an hour, Biden touched on a wide variety of Irish and personal topics which are close to his heart, including his childhood, his love of Irish history, his opposition to the recent U.S./British extradition treaty, his upcoming run for the White House, and the effect it will have on his family.

Irish America: You have made numerous references to your Irish ancestry, most recently in People magazine. Could you tell us something about your roots?

Biden: My mother’s maiden name was Finnegan; I believe her family was from Mayo. She was one of five children. Her grandfather and grandmother on both sides of the family were 100 percent Irish. The Finnegans came over after the first famine, around 1845. The other members of the extended family all came in that period through to about 1880.

There is an ongoing debate as to whether Biden is an Irish, English or German name. My grandfather and my mother were never crazy about it being English and used to say, “Tell him it’s Dutch.” My grandmother was half-French, half-Irish. Her mother’s name was Hannafy. So, on my father’s side there is a minimum of one quarter Irish, and his father would insist that Biden was Irish, but he could never sustain that. He could never know that for sure.

It’s not a very common name.

It’s not common anywhere. I have gotten letters from around the world about it. For example, one fellow wrote me from India saying he had been in the British

Foreign Service, had retired, was in his 70s, and wanted to know if we were related. He traced his roots back to Joseph and Emily Biden, who were in Liverpool in 1668. He thinks they were Huguenots, who came from either Germany or France. Then there is another guy who wrote to me from Australia who said he believed Biden was Irish.

I’m anxious to know if it’s Irish. Maybe this article will help. My brother Jim and I keep saying that we are actually going to take the time and go back.

Tell me about the Finnegans.

My mom’s grandmother and grandfather Finnegan were both deceased before she was born. But her mother, my grandmother, used to tell her how the newly arrived Irish immigrants in Scranton, Pennsylvania, used to go up to Oliphant where the Finnegans lived. My great grandmother Finnegan was the only one who could read Gaelic and she used to read letters in Gaelic for those who could not read the letters from home, and she’d write back in Gaelic for them.

My grandmother used to say, “Remember, Joey Biden, the best drop of blood in you is Irish. ” Her grandfather Blewitt, her mother’s father, emigrated from Dublin, we believe. It’s said that he was a graduate of Dublin college. He settled in Scranton.

One of your relatives was the first-ever Irish Catholic state senator in Pennsylvania, isn’t that so?

Yes, that was Edward F. Blewitt, my grandmother’s father. He was the first Irish Catholic state senator, at least in that region. He was also the co-founder of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, around 1908, and the “Friendly Sons” in Scranton have a plaque showing that he was one of the founding members and vice-president of that organization.

You must therefore have grown up in fairly Irish surroundings?

Yes. A matter of fact, the ambience is probably stronger than the lineage. In other words, I grew up in Scranton, in a predominantly Irish neighborhood and an overwhelmingly Irish parish. It was a city that had some typically eastern ethnic divisions. There was a clear identification with people being Irish; 90 percent of my class mates identified themselves as such.

I have very fond memories of growing up, although I did not think of it until I moved away, to Delaware. My Delaware experience was totally different. The centerpiece of life in Scranton was the church, the nuns, the priests, and the monsignor. Everybody had a sister who was a nun; everybody had a brother who was a priest. Vocations were a big deal.

When did you become interested in Ireland?

My interest in Ireland was first of all a cultural one, not political. I always thought of myself as Irish. I never called myself anything else. I was Irish to the point that my dad used to get angry at times. He’d say, “Your mother’s a Robinette, you’re part French.” I always used to say, “No, I’m Irish.”

Looking back, I remember when I used to go and stay in my grandpop’s house, where we lived for a while. I’d go up to Aunt Gertie, who had the third floor. I’d lie on the bed and she’d scratch my back and say, “Now you remember, Joey, about the Black and Tans, [notorious British mercenary force in Ireland during the War of Independence 1919-1921] don’t you?” She had never seen the Black and Tans, for the Lord’s sake. She had no notion of them, but she could recite chapter and verse about them. Obviously, there were immigrants coming in who were able to talk about it, and who had relatives back there. She was old enough to know about them. If she were alive now she’d be 100 years old. She was born in 1887.

After she’d finish telling me the stories, I’d sit there or lie in bed and think at the slightest noise, “They’re coming up the steps.”

Is there anything you don’t like about the Irish character?

I’ve found out that we are different from the Irish from Ireland. We have a much more romanticized view of our history. I guess, like any Irishman, there are things I love and loathe about us Irish Americans. There is a maudlin side to us. But there is another side. There is a genuine pride, and we are the world’s poets. We have heart and passion.

On the debit side there are such things as the wake. When I look back, I see it gave me sustenance but I hated it. You know, everybody sitting there drinking and the corpse in the next room. It’s brutal when you think about it. That’s the other side, the Irishness of it, such a direct juxtaposition of life and death. There is something about the Irish that knows that to live is to be hurt, but we’re still not afraid to live.

And there is still such a zest for living, even though we as a people go into maudlin periods. My grandfather Finnegan always used to say, “Just remember, Joe, if one Irishman sticks his head above the crowd, another Irishman will lop it off.” Then in the next breath he’d say, “Airways remember you’re Irish.” It was as if he had just come from the old sod. And hell, he’d never been to Ireland. I’m the first one of my family who visited Ireland.

The first time I heard about you being Irish, was when you wrote in Washingtonian magazine that Wolfe Tone was your hero.

That’s correct. I don’t pretend to be an expert but I have a real interest in Irish history. To be honest with you, I picked Wolfe Tone for a number of reasons. One, I did not want to get involved in the question of who among the presidents I liked the best. And, in fact, Wolfe Tone is the embodiment of some of the things that I think are the noblest of all. He was a Protestant who formed the United Irishmen, back in the time of the 1798 Uprising. He had nothing to gain on the face of it, but he sought to relieve the oppression of the Catholics caused by the Penal Laws. He gave his life for the principle of civil rights for all people.

I view him as a somewhat noble figure. He was obviously passionate, which I admire. He had the ability to make his own comfort secondary to the greater good, and he had a genuine honesty and compassion and empathy for the oppressed. And my God, were the Irish oppressed!

You obviously have a keen interest in Irish history, indeed all history.

Yes. My avocation is history. The thing I would like to do most, assuming I ever left this job, would be to teach political history in a university. I enjoy it. I like it a lot. I really do think that you have to know where you come from to have some sense about where you’re going. For instance, I believe there are a lot of lessons to be learned from what didn’t happen at appropriate times in Ireland.

So your strong opposition to the new extradition between Britain and the U.S. (which makes it easier for the courts to hand over Irish political fugitives) while on the Foreign Relations Committee is understandable in that context.

I felt strongly about the treaty. It was the attitudinal thing that bothered me so much. There was an unwillingness to acknowledge the deprivation of the court system in the north, the Diplock courts, no jury trials, et cetera.

Then there was the Administration’s desire to go out and justify the treaty, saying the issue was terrorism. It really wasn’t about terrorism. They never made a case, in my view.

I think that, more than anything else, it was a reflection on how we have never – I’m going to get myself in real trouble here – come to grips with our relationship with Great Britain. There is an overwhelming admiration and awe for the British jurisprudential system, a phenomenal respect for British majesty and power.

In the sense that many Irish are ambivalent about the IRA, we have been ambivalent about Britain. We have fought them and we have loved them. As they are in the twilight of their position as a world power, we are reluctant to take issue with them. And this treaty is something that Margaret Thatcher wanted. So rather than challenge it we shirked it.

You mentioned visiting Ireland. When did you visit?

Oh, over half a dozen times actually, mostly for fun. I like Ireland. I have not made a big deal about it when I’ve gone. I’ve not met with government officials. I’ve just gone. The last time, I guess, was probably 1981. The time before that was before I was married. I went over with my brother Jim and we watched the All-Blacks [New Zealand] play Ireland in rugby. I’m a rugby player – well, I did play rugby. Subsequently, my sister went over, and one of my regrets is that I haven’t taken my mother over yet.

What particularly struck you about the country?

That Irish people must be amused, or bemused, about us Irish Americans. That was one of the things that struck me when I visited Ireland – how out of sync Irish Americans were about what Ireland is. Even just culturally, I mean, beyond the political questions.

Some historians believe that because most of the American Irish are descended from those forced out of the country by the Famine experience, which was in effect their Holocaust, their culture evolved from there, hating the English for good reason, and so on. Ireland on the other hand developed differently.

I think that’s a good point because the famine really is the jumping off point in a big way. Now the Irish in Delaware are very different, truly, very, very different from the Irish in South Philadelphia, in Fishtown, in Scranton, in Pinebrook, in Greenridge, Sandyhill, et cetera.

That is because they came over differently. The DuPont Company in Delaware concluded that the most reliable workers were the Irish. As early as the 1820s, they were sending ships over to Ireland bringing back workers. So the first people who came did not do so as a consequence of the awful wrenching dislocation. When they came, they came into a very paternalistic society.

For example, the DuPont family built the parish church where I live, for their Irish workers. Ironically, for a long time the family held that title to the church, and would not, as rumor goes, give it to the diocese. It was right on the outskirts of the DuPont family compound.

So the Irish up there are very different. For example, we have a Friends of Ireland Dinner in Delaware. It’s protestant and catholic and they’re all Irish. Now in Scranton, “Friendly Sons,” means you don’t have any orange on your body anywhere, do you? Check your underwear (laughs). You know, it’s no foolin’ around.

Speaking of “the orange and the green,” if you became President, would you have a policy on Northern Ireland?

It is presumptuous, in my opinion, to think that any outsider, particularly from across the Atlantic, can have a definitive impact, or even necessarily a positive impact on a situation that is consequences of 300 years of travail. But having said that, I would probably dare tread where angels fear to go, and say it is something that is not inappropriate to have on the agenda when the United States is dealing with what is a true, faithful and legitimate real ally, Great Britain.

Indeed, if it is not inappropriate for us to suggest that efforts should be made in the ‘ Middle East and Latin America, it’s not inappropriate that we should take what is a positive step in Ireland – that is the commitment that the Anglo-Irish Accord be backed up.

Some of us have pushed the dollar side of this Anglo-Irish Agreement with not as much success as we would like. But as President, that is one of the things that I would continue to do. Secondly, the notion of investment in the Republic is important, because I think the stronger the Republic is, the better the chance of an ultimate resolution. Even though it seems unrelated, I think there is a relationship. I think the demonstration of success in the south impacts upon the fear and trepidation the British may have about the north.

Also, I think it’s not inappropriate to suggest to my British friends that they acknowledge the difficulty of the problem. If I was going to be cynical, I would say they deserve it. But you don’t want to make one generation pay for the sins of a past generation.

For instance, the fact that back in history there was a Queen Elizabeth I, who started the plantations that have now come home to roost, is not the fault of some kid living in Liverpool. It’s not his fault. I think that, irrespective of the sad history, the correct notion is there should be strong support for the Anglo-Irish Accord, which is a first step, coupled with steps for meaningful integration, if not coexistence, in the north, between the divided communities.

How would you go about achieving that?

Biden: One of the ways, it seems to me, to deal with that, is to integrate the schools and have Catholics and Protestants educated together. I am not suggesting that is easy. It’s not easy; it’s very, very difficult. We know from our own experience in this country, how difficult integrating schools can be.

I also think the British Government needs to step forward, to speak out more affirmatively against the Paisleys of the North, and treat them with as much disdain as they treat the Provos [Provisional IRA]. I think they’re all bums in terms of all those senseless killings.

My grandfather Finnegan used to talk about 1916 and there was a notion that to be part of the IRA then was a noble thing. If you read the current Provos’ manifesto to me, an Irish American, or just an American, I cannot believe that the Irish Americans here would support it. If I stood up in Fishtown, which is an Irish section in Philadelphia or went into a bar and read the manifesto of the Provos, they’d say, “You communist pig.” Forget it, they’d have me on the floor.

The other thing that is important in the south and in the north, where unemployment is rampant, is jobs. I used to have a teacher, Sister Michael Mary, who used to say, “An idle mind is the devil’s workshop.” An idle man or woman is a discontented person. Idleness breeds on itself, enlarges the vicious circle.

I think legislators over there have to take more risks. I have a sense of the frustration and confusion they feel, even those who wish to push more. I guess the best we could do from here is gently prod and strongly support when the prodding occurs. I believe it’s important to recognize the inevitability of unity, but not with a timetable.

To do that, I believe, would be much less troublesome if there was an integration of the communities based on mutual trust and respect. I think that one of the reasons that you have resistance, on both sides, to integration is that neither extreme wants that to occur.

Such sentiments on the part of a contender for the job of President of the United States would probably be denounced as interference by groups in Britain, certainly, perhaps even in Ireland.

If we have a moral obligation in other parts of the world, why in God’s name don’t we have a moral obligation to Ireland? It’s part of our blood. It’s the blood of my blood, bone of my bone. A nation should not deny its cultural ties and heritage. It’s not that we don’t have phenomenal cultural ties with Great Britain, of which I’m proud. Although I acknowledge it’s dangerous; any thing that is done over there will take real courage. I want to support it.

To what extent do you think the Irish themselves and their failure to rid themselves of the British or live in peaceful co-existence are part of the problem?

You know, I’m not sure. When you look at it from the standpoint of Irish history, what choice did we have? It’s not like we didn’t try. If you subjugate a people for generations and take their land, their birthright, their right to read, their right to eat, it has to have a long-term debilitating effect. But to me, the fact that we have never lost the sense of nobility and the culture and learning is important. Don’t forget the monks were hanging off the cliffs of Skellig Michael in the Dark Ages, protecting the outpost of not only Christianity but also learning.

I am not one of these guys who is going to go back and tell you that all culture resides in Irish culture, but there is a great deal to be proud of. Not withstanding all of that, the surprise to me is that they continue to maintain a sense of dignity.

Could you elaborate on that?

Look, suppose you just landed on this planet and said, “O.K. I’m going to press a button that will instantly allow me to see four hundred years of the history of this section of the world.” You’d say, “My God, how is there anything left.” It took a hell of a long time to get there, and it’s going to take a hell of a long time – pray God, not four hundred years – but a hell of a long time to get out.

I was reading in your magazine [January issue] about Michael Collins and the debate still raging about how and why he died. I thought about my grandfather engaging in fierce debates and talking about De Valera. Was he right? Was he wrong? You know, that was the culmination of 300 years of war, that civil war. What other nation has been as bled of its people for so long?

Turning to your own political career, how do you feel about the description somebody wrote of you as “Irish Catholic, tragedy-visited but with none of the emotional baggage the Kennedys carry, who could inspire another Camelot.” Do you see yourself in that way?

No. I see myself as an Irish Catholic. I am not the heir to, but I feel a genuine kinship to the passion and the dreams of Camelot. The thing that always lifts men and women to great heights, to those heroic proportions, is not specific programmatic initiatives but insights as to who we are and what we are, the notion that we can be larger than ourselves for the moment.

No. I see myself as an Irish Catholic. I am not the heir to, but I feel a genuine kinship to the passion and the dreams of Camelot. The thing that always lifts men and women to great heights, to those heroic proportions, is not specific programmatic initiatives but insights as to who we are and what we are, the notion that we can be larger than ourselves for the moment.

But I don’t view myself in a tragic role. I’ve had my tragedy [first wife and a baby daughter were killed in a car crash] but so has everyone else. That’s part of what I mean about what it means to be Irish. Not only Irish, what it is to be human.

There are tens of thousands of women and men in this country who have suffered more than I have. I mean, they have suffered what I have suffered but they have not had the phenomenal network I had available to me, getting me through.

In my family it’s not a question of having to ask; if you have to ask, then it’s already too late. After my difficulties I had a mother and sisters who moved in and raised my children, and a brother who stood by me. I was really lucky. Then God gave me another good Presbyterian girl who put my life back together again.

How important was Catholicism for you. Was it only after the tragedy?

It has always been important. To be honest with you, the tragedy shook it a little bit, for a moment. You kind of feel sorry for yourself, thinking, “Is there a God?” Does my religion mean anything? Why would this happen?” I think everybody goes through that when difficulties occur in life.

I am not suggesting to you that I am a deeply religious man, but I deeply believe in my religion. It’s very important to me and I have to admit that sometimes I don’t know whether it’s cultural, theological or practical. I’m not sure why, but I believe that some real wisdom has accrued over 1,987 continuous years of Catholicism, as long as you take it in a way that understands that there are significant mistakes that my church has made, but that it has an amazing resilience which I admire and I think that it’s an important part of my life.

For example, I don’t know why, truthfully, but I can’t miss mass. I never miss mass. Even the last two weekends when I went skiing and I dragged myself off the slopes to be sure I got to five o’clock mass in Salt Lake City. We walked in and there was an Irish priest just walking down the aisle; and he looked at me and said, with an Irish grin, “Boys, you’ re a little late.”

I looked down and said, ”Jeez, Father, I’m embarrassed.” So we stepped out and everybody was walking out. I said to my boys, “Look, wait until Father goes back into the sacristy and we’ll make a visit, light a candle and say a prayer at least.” So we walked in and saw Father in the back in the vestry. He turned around and started laughing. He was from Tipperary. He said, “How about if I give you some communion?” So we went up and he served communion, and I said, “Father, how about coming out to dinner with us?”

So we sat and shot the breeze, we had a great time, for about two and a half hours. We talked a lot about Ireland and he asked, with typical Irish exaggeration, “Have you ever visited the most beautiful spot in the world?” I just took a stab at it, and said, “I’ve been to the Ring of Kerry a number of times.” He said, “How did you know?” Then he started telling me about when he was a kid and went camping there.

At any rate, I practice my religion. It’s no big deal.

It’s said that one of John F. Kennedy’s biggest legacies was that he showed that being an Irish Catholic was not a liability. Do you agree?

I think that’s correct. Being a Catholic more than an Irish Catholic. It didn’t have as much to do with him being Irish as with his being Catholic. I really believe that President Kennedy did really settle the question about Catholicism in this country, in a major way.

How about Governor Cuomo as an Italian Catholic?

Editor’s note: this interview was conducted before Cuomo dropped out of the 1988 Presidential race and at a time when his background was coming under increasing scrutiny.

I think Cuomo is getting a bad rap on the Italian rather than the Catholic part. But I don’t know. I think that Governor Cuomo is unjustly getting criticism in part because he has had the w ill and the knowledge to engage the Church and be engaged as a thinking Catholic. So he has conducted his debate with God in public.

He has engaged in and spoken at length, I think to his credit, on the source and depth of his beliefs. It would be no different than if you were a Presbyterian saying, or writing in your diaries, “Today I went back and re-thought again whether Calvin was correct and if predestination is something I should be bound by.” Then everybody would be saying, “Hey, wait a minute, how about this Presbyterian Scotsman we have here.”

You’re a very young man comparatively. Does the prospect of being President frighten you?

The prospect of being President is a daunting one. Maybe it should frighten me. It doesn’t frighten me, but it chastens me to realize that I’m not sure that there could ever be any woman or man who could be prepared, in a purely objective sense, to be President of the United States.

I think that the President of the United States affects the fortunes of the free world, more than any other single person. If you look at it in those terms it’s a chilling thought. But I think that the way to deal with problems is to look at the pieces you can handle. Look at it, not so much in terms of the enormity of the task, but in terms of the pieces of the task all of which you think you can handle.

But if you look at it in total, you say, my goodness, I’m not, nobody is, capable of doing that.

How about the nomination process?

Well, that’s the hardest thing. I think the most difficult question, at least for me, relates to what impact it will have upon the family. Not the impact on whether they can handle it or not handle it, but whether or not it will impact on my ability to be with them, to enjoy with them, to share with them, to be part of the family. These are the most important considerations to me.

If I run, I’m not going to like the fact – a trivial thing in most people’s minds, they will probably read this and say, God, this guy must be crazy – that I will miss most of my son’s football games.

I go home every day. I like very much getting up every morning with my five-year-old daughter, getting her dressed and fixing her breakfast. She doesn’t need me to do that. As a matter of fact, she has got to the point now that she can do it herself but she is patronizing me.

It’s a two-hours each way for me, from this chair to my front door. [Biden commutes from Washington to Wilmington.] As my dear mother used to say, if you hung by your thumb long enough you’d get used to it. I’m doing it long enough, and it’s worth it. It’s worth the effort, even though I leave here at nine O’clock, and don’t get home until 11.

People here, including my staff, say, “What are you going home for.” But I feel good about it. I feel good about being able to walk in and go up when they’re asleep and kiss my 18-year old goodnight and my 17-year old goodnight, and go in and lie down with my daughter for two minutes. Wake her up a little to let her know I’m there, scratch her back and tell her to wake me up in the morning. To me they are important things. Not just to me, but also to 99 percent of the people on earth, I think.

The campaign grind would really affect your close family life then.

Yes. If being President were the same as campaigning for President, then I would not try to be President. But as President, the train doesn’t leave until you get there [laughs.]

Granted, there is phenomenal pressure, but I believe I can handle the pressure. My family can handle the pressure. The question is, “Am I going to have any prospect of being with them, to handle it together with them?”

Surely, though, most politicians are forced by their jobs to have less time for their families?

I am not one who, in my life, subscribes to the notion that it’s not how much time, but the quality of the time. That’s not my experience with children.

My experience is that it’s vital that Daddy be available. When they catch a fish, they want to show you the fish right then. They don’t want to wait for four days for you to say; “now we have three hours of quality time. It’s you and me.”

Most of the important conversations, the most meaningful things that have occurred in my relationship with my children have not been planned. They’ve been spontaneous discussions. These are the times that make you say, “God, I’m glad I’m a father.”

I don’t mean to imply that quality time isn’t better than no time, but the best time is the availability of time. We have a rule in my family. The kids call it “wild card.” From the time that they were little kids – it really came about when they were four and five – after the accident, they have been able to say, “Dad, I want to come with you today.” Regardless of where I’m going. It makes no difference. They come, period.

I had almost forgotten it, because the boys of late have not exercised their ‘wild card’ very much. I was going to make a Westchester University commencement speech, for their fall commencement. As I’m walking out the door, my daughter said, “Daddy, I decided I want to come.” A reporter for the Congressional Quarterly is covering me this day, and she looks at me like, “you’re late.” So I said, “Oh, honey, you wouldn’t like it.” She said, “Daddy, don’t say you talk too long. I like to hear you talk.” I said, “Honey it’s going to be boring.” She said, “Daddy, I want to come.” I said, “Oh Honey.” The she said, “Daddy, wild card.” I ran upstairs, changed her clothes in three minutes, packed a little duffle-bag for her and we all went off to the commencement.

So everybody tells me, “You can’t do that and run for President.” Well, I refuse to accept that. I am probably going to get beaten, but I’m not going to accept that.

Sounds like you’re definitely going to run?

If I run [laughs].

Would you go to Ireland if you were President?

Sure I would – try and stop me – I’d love it. That’s like asking Cuomo if he would go to Italy if he were elected.

Senator Biden, thank you.

Leave a Reply