By Pat Fenton

As sure as Brendan Behan had his Dublin, Ireland, Seamus Heaney had his Northern Ireland, and Dylan Thomas had his Swansea, Wales, Pete Hamill had his Brooklyn. And like them, he wrote about it his whole life. And like them, he was always pulled back home again. And he did it with this literary skill that only comes along every so often. Sadly he’s gone from us now, but like these other great writers his words will stay with us forever.

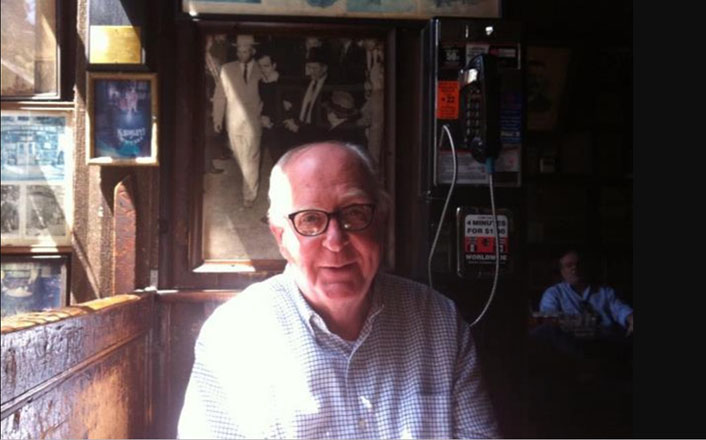

Listen to him describe a rainy night in 1970 where he’s sitting at a table with Frank Sinatra in P.J. Clark’s saloon in New York: “On this night in the rain-drowned city, we were safe and dry at an oak table in the back room of the saloon. Clarke’s was , and remains, a place out of another time, all burnished wood, and chased mirrors, Irish flags and browning photographs of prizefighters.

Photo hmag.com

A few aging men at the long, bright bar could gaze out the windows and still see the Third Avenue El, gone since 1955, or the Irish tenements that were smashed into rubble and replaced with steel-and-glass office buildings. They were each drinking alone and looked as if they remembered other nights too, evoked by the music of the jukebox. “The music playing is Frank Sinatra. Pure vintage Pete Hamill.

Nobody really knows where this wonderful poetry of words comes from, nobody. Even if Behan and Dylan Thomas were still around they couldn’t tell you. Even if Jimmy Breslin was still around he couldn’t tell you. You’re either blessed with it or you’re not. Pete Hamill like Brendan Behan and Dylan Thomas and Breslin was.

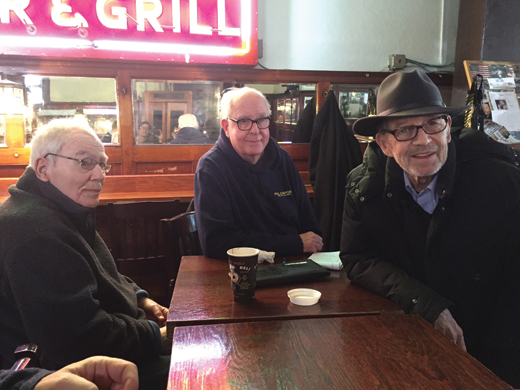

(Photos: James Higgins)

He lived down on a part of our Brooklyn neighborhood, 7th Avenue and 12th Street, that was not really Windsor Terrace or Park Slope, but a part of it that was cushioned in between both places. This is where he grew up: cold water flat with nine kids and one bathroom, his father Billy Hamill from Belfast, who had a wooden leg, worked the line all day long in the crushing heat of a nearby factory. When the evening comes there is a little solace for Billy Hamill in Rattigan’s Bar, and that’s it until the whole routine starts up all over again the next morning.

Pete went back once with a reporter from the Daly News and as he described it to me, nine kids and two adults crammed into this tiny apartment he said, “Christ Almighty how did we do that.”

It was a short distance from Holy Name Church where as a young boy he served mass as an altar boy. He would head up the hill to 9th Avenue and Prospect in the early morning hours, past Farrell’s Bar, past Ebinger’s Bakery, past the United Meat Market, and enter into the quiet of the church where weddings were performed; babies were baptized, where the long dirge of funeral masses would drone on. All of it would later become grist for the mill when he started writing.

Over the years I would have long conversations with Pete over the phone. We would talk every few month’s about everything from the characters we both knew from the neighborhood, people with names like the junkie Bubba Lee, to literature, and the craft of writing.

He told me that he got the idea for writing his book Forever one chilly October afternoon when he was sitting down at the Battery. “I was just sitting there alone, thinking, watching people go by, and looking out in the harbor.” It made him think of how his parents came through this harbor, long, long days ago when they emigrated from Ireland. “And I said to myself, ‘I wish I could live forever.’ And I laughed to myself as I thought that’s not a bad idea for a novel.”

We often talked about the innocence of the neighborhood in the 50s , slow dancing down at the Caton Inn to the sound of Joni James singing “My Funny Valentine,” weddings at McFadden Brothers American Legion Post on 9th Avenue, kegs of draft beer, tables filled with cold cuts, set ups of rye whisky, and “glorious” Irish working-class honeymoons to the “far away ” Poconos. And somehow many of those marriages lasted, forever.

We talked about saloon nights when men stayed sober when information that they were hiring down at The American Can Company, or out in the Quaker Maid Factory at Bush Terminal passed around the bar. “Get there early in the morning. Wear a suit and tie.”

But mixed in with the innocence was this toughness of the neighborhood, the violence. One afternoon he recalled to me a gang fight in Prospect Park in the 50s that we both remembered. A member of The Tigers, one of the toughest Irish and Italian street gangs in Brooklyn at the time, got shot and killed by one of the “South Brooklyn Boys.” He described to me how he remembered the next day where he saw some of the Tigers standing under the marquee of the Minerva Movie house on 7th Avenue, some of them crying as they read in the Daly News and the Mirror the report of Giacomo Fortunato’s death. And that too went into the mix of his writing style.

So this is a small part of the Pete Hamill I knew as a friend, and certainly a mentor. He was Brooklyn. He was McFadden Brothers American Legion Post on 9th Avenue, he was Bartell Pritchard Square in front of The Sanders Theater and “the totes’, two large columns at the 15th Street entrance to Prospect Park where we all drank containers of beer on Saturday nights when we were young. He was the Caton Inn, and Leo’s pool hall on 7th Avenue down near where he lived, and the Royal Tailor on 5th Avenue next to the 72nd Pct. where we all got our first pair of peg pants in the 50s, and the Shoe Box a few doors down where we first got our first pair of “French Toed” shoes.” And he wrote about it all.

After I read his first column in the old New York Post after coming home to Brooklyn, home from the military in Europe in 1963, I wondered who is this columnist writing about our neighborhood, writing about Farrell’s Saloon, writing about the factories many of us worked in, writing about us.

And that’s what he did very well throughout most of his career, he wrote about the ordinary people of Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn. Yeah, Frank Sinatra was part of his life, and he got to attend the Academy Awards in a tuxedo once with a movie star, but he still wrote about Farrell’s Bar in his books, the bar where his father Billy liked to drink in. In his book The Gift he wrote about Boops bar on 17th Street and 10th Avenue and how he headed there after he was discharged from the Navy, looking for an old neighborhood girlfriend.

If I could imagine any music playing as the score in Pete Hamill’s life in Brooklyn it would the music of Santo and Johnny’s “Sleepwalk.” They lived down on 18th Street in Windsor Terrace. The slow, beautiful continuance of their music that seems to go on and describes it all.

In 2012 he came out with a book of short stories titled The Christmas Kid and Other Brooklyn Stories. I remember that during Hurricane Sandy my family and I were forced to evacuate our house and the motel we were staying in had a blackout. Sitting in that dark room, some light from candles, a friend of mine from Windsor Terrace, Bob Rice called me and said “Pat. I have something to cheer you up.

In 2012 he came out with a book of short stories titled The Christmas Kid and Other Brooklyn Stories. I remember that during Hurricane Sandy my family and I were forced to evacuate our house and the motel we were staying in had a blackout. Sitting in that dark room, some light from candles, a friend of mine from Windsor Terrace, Bob Rice called me and said “Pat. I have something to cheer you up.

I just brought Pete Hamill’s new book and the dedication page goes on for two pages naming people from our old neighborhood. And you’re in it. The New York Times later said that “the unusually long dedication page would be interesting to just publish on its own.”

“This book is for – in no particular order – the people from my Brooklyn hamlet,” he opened it with. The first name that was listed was his best friend who he grew up with and hung around with for the rest of his life, Tim Lee. The list of names went on, reading like the cast list from Wilder’s “Our Town.” Jimmy Houlihan, the bartender from Farrell’s Bar is listed, and Maureen Crowley, and Dotty Condril, and at the very end of it, the bank robber Willie Sutton who was known to drift in and out of the Irish saloons of the neighborhood when the police were looking for him. There were no cell phones then, and no one from the neighborhood ever thought about turning him in. This too, was Pete Hamill’s Brooklyn.

He ended the dedication with these words: “All were residents of my Brooklyn shtetl. All remain alive as long as some of us are alive.”

I picked up a copy of it and one day I asked him to sign it for me. He wrote “For Pat Fenton. Who has made certain that the past might die, but never disappear. Onward, Pete Hamill.”

Pat Fenton grew up in Windsor Terrace in Brooklyn, and worked as a court officer. He has written for a number of publications, including his popular piece on Farrell’s Bar for Irish America. He also wrote a play, “Stoopdreamer,” about the historic Irish saloon.

CORRECTION: Earlier, I shared this tribute I wrote on Pete Hamill and somehow I wrote that he lived in a tenement on 7th Avenue in Brooklyn and there were nine kids in his family and two adults living there. I meant to write seven kids and two adults. But still, seven kids and two adults living in a walkup tenement with one bathroom is not easy. I know, I grew up in one not far from there on 17th Street in Windsor Terrace, top floor left.

loved this!! i was born in 50s, and my deepest happiest childhood memories were from east 8th street near Caton Ave, running around my aunt ediths house with 10 to 20 cousins at any given time while my parents aunts and uncles laughed their heads off over gallons of coffee, crumb cake and coffee danish rings….theyre all up in heaven and i hope theres a cup for me waiting. janet