By Tom Deignan

Constance Curry

As the U.S. struggles to reconcile its ideals of equality with a horrific legacy of racial oppression, the lives of John McNamara and Constance Curry – uncompromising Irish Americans, both of whom died this summer – teach us valuable lessons about race, struggle and progress.

Constance Curry was born in 1933, in Paterson, New Jersey. Her parents came to the U.S. from Belfast, settling in a city with a long history as a hub of clothing manufacturing – and labor conflict.

But unlike most other immigrant factory families, the Currys moved down south. When Constance was in the 3rd grade the family relocated to Greensboro, North Carolina, where her father got a job in the textiles industry.

These were Jim Crow days in the American south, where rigid – and violent – racial segregation was practiced.

Curry’s Irish background, however, put her on a path to become an important player when the U.S. Civil Rights movement gained steam in the 1950s and 1960s.

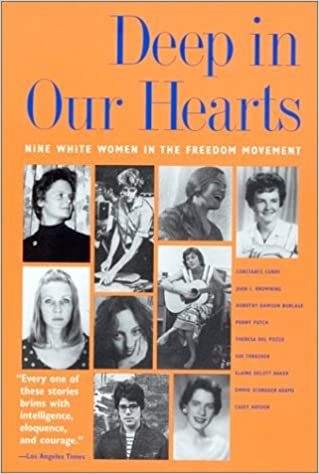

In a 2000 book entitled Deep in Our Hearts, Curry – who died in June at the age of 86 – wrote: “It is clear to me that the Irish struggle got planted deep in my heart and soul at an early age, and that its lessons and music and poetry were easily transferred to the Southern freedom struggle.”

In a 2000 book entitled Deep in Our Hearts, Curry – who died in June at the age of 86 – wrote: “It is clear to me that the Irish struggle got planted deep in my heart and soul at an early age, and that its lessons and music and poetry were easily transferred to the Southern freedom struggle.”

To African Americans at the forefront of the Civil Rights movement, Curry was a versatile, valuable ally.

“She could move comfortably anywhere in the South,” Andrew Young, the Civil Rights activist and former Atlanta mayor, told The New York Times last month. “She was one of the few people that could go to an N.A.A.C.P. meeting or a revival and be at home, and at the same time go to the upper-crust Episcopal Church and hold her own.”

Young added that Curry could also “move in and out of the white community and gain a sense of what’s really going on.”

By 1960, as sit-ins at lunch counters across the South became a tactic used to confront legal segregation, Curry was working for an Atlanta group called the National Student Association.

She ultimately “spent her entire adult life committed to social justice,” the Times noted, adding, “Outgoing and determined, Ms. Curry was a bridge between Black activists and white Southerners who wouldn’t often talk openly about their feelings on integration.”

“But they would (talk) with Connie,” added Young, who first met her in 1961, and later recruited Curry to work in his administration.

Curry’s role in the Civil Rights struggle did not become more widely known until she wrote the 1995 book Silver Rights, about a Mississippi family’s battle against segregation.

To learn more about Constance Curry visit the Rose Library blog from Emory University.

James McNamara

John McNamara faced a similarly fierce challenge in the 1960s Jim Crow south.

McNamara – who died at the age of 88 in late July – was best known as the manager of the ill-fated 1986 Boston Red Sox baseball team. But decades earlier, African American baseball stars like Reggie Jackson saw the passionate and principled stuff John Francis McNamara was made of.

He was born in California to an Irish immigrant father who’d first landed (fittingly enough) in Boston. McNamara Sr. then crossed the continent, working railroad jobs.

McNamara’s father died when his son was just 12. But his uncles were avid athletes, and by the time McNamara graduated from Sacramento’s Christian Brothers High School, he was an All-City baseball as well as basketball player.

He signed a minor league contract as a catcher, and played parts of 15 years in the minors.

“I could catch and I could throw,” McNamara once said. “But I knew I wasn’t going to make the big leagues. I was too small [5-feet-10, 175 pounds] and I couldn’t hit. I was married and had four children to think about.”

McNamara, of course, did make it to the big leagues – as a manager.

But before he served as skipper to six different major league clubs from the late 1960s to the mid-1990s, he was a minor league manager in the mid-1960s. That meant games in the south, where African Americans players were unwelcome at segregated hotels or restaurants. In 1966, one of the budding stars on McNamara’s team was future Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson.

Jackson also made sure to mention McNamara in his 1993 Hall of Fame induction speech.

“I learned to understand friendship and sensitivity from a very special friend by the name of John McNamara,‘’ Jackson said in Cooperstown. “He was my manager, and he would not allow the team to eat in a restaurant where I was not allowed to eat. I always wondered why we ate sandwiches on the bus and made only essential pit stops. I understood care from that. I’ll always remember you, John, for your dignity and sensitivity and for stepping up at a time when very few did.‘’

In baseball lore, McNamara will always be remembered for leaving Bill Buckner in to play first base in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series. The Red Sox were one strike away from winning their first Series in decades, but Buckner made a crucial error, allowing the New York Mets to win the title.

But McNamara – who did win 1986 Manager of the Year honors – never had any regrets.

Why should he? He’d already helped win so many more important battles.

By Tom Deignan

Best-Selling Dublin-born author Emma Donoghue has a brilliant and timely new novel out. Set in an Irish maternity ward during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, The Pull of the Stars explores the challenges and heroism of nurses and other health care workers, while at the same time tenderly chronicling the loves and losses of their inner lives. Tom Deignan speaks to Donoghue about this new book, Irish history, her Academy Award nomination (for the movie of her book Room), and her next Hollywood project.

Tom Deignan is an author, teacher, and columnist for the Irish Voice and Irish America (tdeignan.blogspot.com).

Leave a Reply