By Edythe Preet

In the 16th century Elizabeth I was Queen of England. Spain and England were at war, and their armadas stalked each other on the open seas. Certain Irish sailing captains who swore allegiance to neither nation raided both fleets for profit. Some called them pirates. Some called them heroes. One became a legend.

Her name was Granuaile. Grace O’Malley. Pirate Queen. Many tales are told of this extraordinary woman, but the one I love most concerns her particularly unusual way of reminding a certain nobleman that the Irish are known for their hospitality.

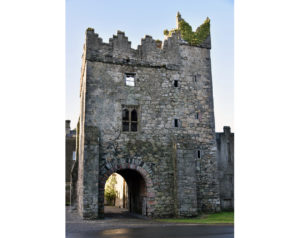

The year was 1576. Some accounts say Grace had been to visit Elizabeth, others that she was returning from a `trading’ voyage. Where she had been matters little. When Granuaile and her fleet returned to Ireland, they pulled into Howth Harbor north of Dublin to replenish supplies before sailing around the north coast to their home in County Mayo. It was dinner-time, and Grace had been many days at sea. She hied herself to the nearest castle intending to request a meal. But the door was locked, and the Lord of Howth refused her entry.

This was a serious violation of the Brehon Law that required all to share hospitality with travelers. Furious with his disregard of the mandate, Grace stormed back to her ship. Along the way she chanced upon the Lord’s son, Christopher. Seizing him, Grace sailed back to her home on Clew Bay. When the Lord learned of the abduction, he hurried to Connaught and offered to pay any price for his son’s safe return.

Grace scorned his offer of ransom. Instead, she demanded that in exchange for the boy the gates of Howth Castle would never again be closed to anyone who sought hospitality and a place would forevermore be set at the Lord’s own table just in case a hungry traveler might happen by. For four centuries the promise has been faithfully kept.

I had occasion to remember the story at a Los Angeles pub called Irish Times. A friend and I discovered the place on Saint Patrick’s weekend when we went hunting for a traditional Irish breakfast — not an easy thing to come by here in Tinseltown. When the urge to indulge hit again, we faithfully traipsed over to the source and discovered much to our chagrin that the kitchen was closed. The owner, Jim McGurrin, had passed away.

We called for two pints of ale and toasted his memory with the barkeep. We had only met Jim once and the St. Pat’s crowd was heavy, but he found time to chat with us even though other groups were obviously regular customers. Jim was a fine Celt of a man. Tall, jolly, gracious, father of five, devoted husband, sponsor of the local soccer team, die-hard fan of Irish music, and one of the best bread makers I’ve ever encountered. His soda bread and brown bread could have won blue ribbons.

With only one other customer on hand, the barkeep had time to chat. Turned out he was Jim’s son, Sean. We talked about his dad, the city they’d come from — Howth, and Granuaile, for her lesson in manners is one of Howth’s most famous tales. When I mentioned a memorable meal I’d had at The King Sitric, a restaurant alongside Howth harbor that’s famous for its seafood and vast wine cellar, Sean remembered we’d come for breakfast. He leaned across the bar “Just sit right there, I’ll fix you a plate.”

A few minutes later he brought us platters heaped nigh with sausages, black and white puddings, thick crisp chips, a stack of bread, and a pile of butter pats. Howth hospitality half a world away.

The conversation shifted to bread and the many things the Irish do with a simple slice. Sean told us about a sandwich called a “chips buttie.” A favorite midnight snack of Howth’s all-night pub crawlers, it consists of buttered white bread smeared with ketchup and rolled around a handful of chips. I gamely gave it a try.

A deluge of childhood memories flooded in with the first bite. I remembered my father had a habit of making buttered bread sandwiches with just about anything. Slices of cold Sunday roasts. Fried eggs. Cinnamon sugar. String beans. Broccoli. Plain lettuce. Baked beans were his #1 favorite.

Bread and butter are mainstays of the Irish diet. Every homemaker has treasured recipes for soda bread, wheaten bread, scones, biscuits and farls, and no table is complete without a tub of sweet creamy butter.

Ancient Ireland was a land of cattle where healthy stock and an abundance of milk made all the difference between prosperity and poverty. Milk products were known as ban bhia or white meat and included all possible variations of milk: fresh milk, sour milk, buttermilk, cream, butter, curds and cheese. Every farmhouse had its butter-making equipment: chum, crockery pans, ladles, skimmers, scoops, stamps for decorating butter with floral designs, and pats to cut butter into convenient sized pieces for the table.

The fairies, or sióga, played an important part in everyday rural life, and many things were explained by magic. The way golden butter solidified from milk was especially mysterious and many superstitions were associated with butter-making. Occasionally butter refused to separate from the milk, and people believed that someone with an evil eye had enchanted the cow. To counteract such spells, magical rowan tree branches were tied to the churn dash, or salt, which evil creatures detest, was dropped into the milk. All visitors were expected to help chum, except would-be suitors since it was believed that churning would cause bachelors to become impotent.

If the household’s butter was not going to be eaten immediately, salt was added as a preservative, but this was considered an inferior product. Like every other aspect of Irish life, there was a Brehon Law that addressed butter. Sons of farmers ate gruiten (salted butter) with their porridge, sons of chieftains had im ur (fresh butter), and sons of kings received sweet butter and honey.

Butter was stored in baskets, cloth bags, or leather sacks, and turf cutters have discovered many examples buried in peat bogs. When a family made more butter than it could use, the excess was buried in a cool moist bog to keep from spoiling. This method of keeping butter from turning rancid was also used by herders in mountain pastures who made butter all summer long but did not sell it until harvest fairs.

Butter has always played an important economic role in Ireland. At one time, every family had a cow to provide its essential milk, butter and cheese. On a small scale butter supplied a means of exchange for other food items and materials, or it was sold at market for a meager income. In places where production was high, butter was exported. County Cork became the center of Ireland’s dairy industry, and in the 18th century Cork City was considered “The Butter Capital of the World.” From its Butter Market and Butter Exchange in the Shandon district, the fresh butters of Cork and Kerry were salted and exported to the best tables of Europe.

Butter still holds a primary place of honor in the Irish kitchen. It is drizzled on meats, stirred into sauces, beaten into cakes, puddled in bowls of colcannon, plunked into porridge, and slathered thickly on all manner of bread at every possible opportunity. And when guests come to call, a platter of “butties” and a hot pot of tea are evidence of Irish hospitality at its best. Sláinte!

Sweet Whipped Butter

1 pint heavy whipping cream

Chill cream, a medium size stainless steel bowl and electric whipping beaters thoroughly. When cold, whip cream as you would to make whipped cream but continue whipping until it turns a pale yellow color and separates into clumps. Be patient, this will take time. Ladle into a plastic container and chill. Serve instead of commercial butter. Makes 1 pint.

Whiskey Sauce

1/2 pound butter, softened

1 cup sugar

2 eggs, beaten

1/2 cup Irish Whiskey

Cream butter and sugar until light and fluffy. Transfer to top of double boiler, set over gently simmering water, and cook stirring frequently until sugar is completely dissolved. Whisk 4 tablespoons of hot butter mixture into eaten eggs. Stir mixture back into melted butter-sugar and whisk until thickened, 4 to 5 minutes. Remove sauce from heat and stir in whiskey. Add more whiskey to taste if desired. Makes 2 cups.

Some interesting information on Grace O malley, I heard they were going to make a movie about her but it fell flat?

loved the the information on Irish bread and butter. If I ever get to Los Angelus I must remember to visit the Irish Times.