After the discovery of gold in the Klondike, 100 years ago, some 100,000 people headed north in search of a quick fortune. Only a handful of them found it, and of that handful, only one was a woman.

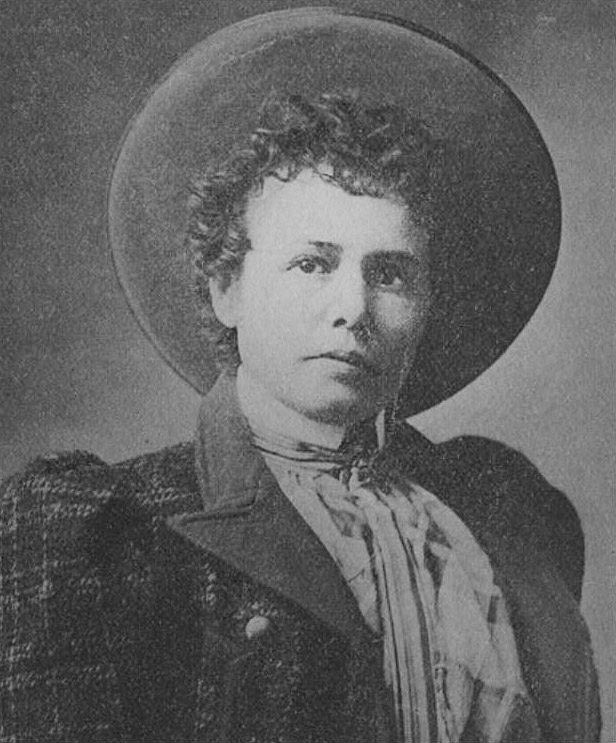

When Belinda Mulrooney died nearly penniless in a nursing home near Seattle in 1970, few of her neighbors suspected that, seventy years earlier, she was known as the Queen of Grand Forks, and the richest woman of the Klondike. James Oliver Curwood used her as a character in his novels, and Klondike historian Pierre Berton claims she owned a dog that inspired Jack London’s Call of the Wild.

Belinda Mulrooney didn’t go after riches the same way most of the Klondikers did – trying to dig it out of the frozen earth or pan it from the icy rivers. Belinda grew up the daughter of an Irish coal miner in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and wanted nothing more to do with that sort of backbreaking labor. She was determined to make her fortune with her wits.

She was well on her way to doing it before the Gold Rush began. In 1893, when she was only 18, she went off alone to the Columbian Exposition in Chicago and opened a restaurant that proved popular enough to net her $8,000 — a lot of money a century ago. Then she promptly lost it in a bad business deal in California.

But she wasn’t the sort to head home in defeat. Instead, she took a job as a stewardess on the steamship City of Topeka, which sailed up and down the Northwest coast. On her very first voyage, she made a strong impression on the ship’s captain by delivering a passenger’s baby, while the captain stood outside the door of the cabin, reading instructions from a medical manual.

So impressed was the captain with her level-headedness that he put her in charge of ordering all the ship’s supplies. Belinda used the situation to her advantage by buying a little extra, in the form of fancy hats and dresses, which she sold to the Native American women in the coastal towns.

It was a comfortable setup — but too tame for Belinda. By the time the ship docked in Alaska in the spring of 1897, she had boosted her net worth to $5,000. When she got wind of the gold strike made the previous fall, a few hundred miles to the North, she blew her savings on cotton clothing and hot water bottles and set out, in the company of two Native Americans, on a raft down the river, headed for the gold fields.

As they neared the boom town of Dawson, she drew her last half dollar from her purse and flung it ceremoniously into the river. Never again, she vowed, would she have need of such a paltry piece of change.

She was right. For most Klondikers, Dawson didn’t prove the El Dorado they had come there to find. But for those entrepreneurs who were lucky or canny enough to provide something the gold-seekers needed or wanted, the town was a veritable gold mine.

Belinda sold her stock of clothing and hot water bottles for a cool $30,000 — a 600 percent profit. She used the capital to open a lunch counter that did a brisk business with customers who paid in gold dust and nuggets. On the side, she became a contractor, hiring men who’d had no luck in the gold fields to build cabins that sold to the steady stream of cheechakos (newcomers) the moment the roof was on.

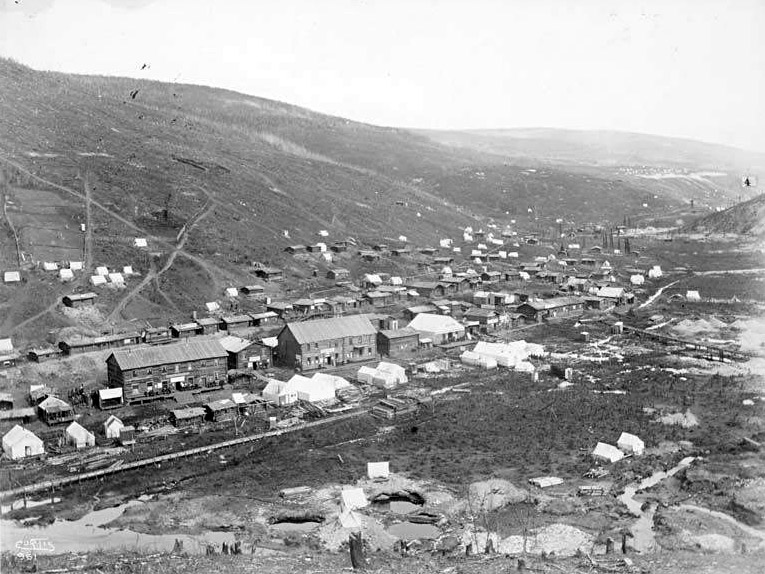

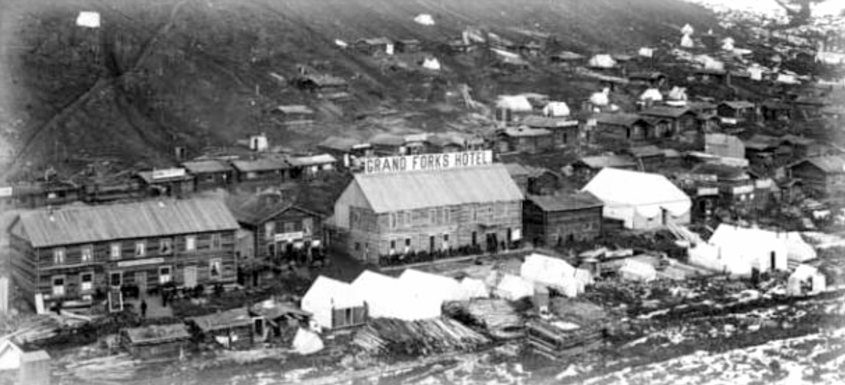

Again, Belinda had made a comfortable and profitable enterprise for herself. And again, she wasn’t satisfied. She wanted to be where the action was – the gold fields themselves. Ignoring the advice of her fellow businessmen, who considered her foolish if not downright crazy, she began hauling lumber on a broken-down mule to the rough-and-ready settlement of Grand Forks, a stone’s throw from the original gold strike, near the junction of the Klondike and Yukon Rivers. The roadhouse she built there of logs chinked with mud and moss gave the prospectors a more convenient place to get rid of their newfound gold. What did they care that she charged a dollar for a single egg, and the highest prices in the Territory for a shot of whiskey or a cigar? There was always more gold where that came from — or so it seemed.

One of Belinda’s best customers was Big Alex McDonald, the King of the Klondike, who had grown rich by buying up gold claims cheap when their original owners threw in the towel. He and Belinda briefly became partners that fall, when a supply boat wrecked on a sandbar; they bought the cargo and made plans to salvage it. Big Alex got to the wreck first, and took as his share all the food — something that was in increasingly short supply as winter drew on and all routes to the Outside closed. He left Belinda only some cases of whiskey and a large assortment of rubber boots.

Belinda was not happy. “You’ll pay through the nose for this,” she promised him. As usual, she was right. When the spring thaw came and the ground turned to mush, Big Alex was in sore need of waterproof boots for his workers. Belinda just happened to have plenty, and she sold him the whole lot – at a hundred dollars a pair.

Already, Belinda was better off financially than the vast majority of the miners. But money wasn’t everything. She was looking for something more – respectability, maybe. In Dawson, at least, that was something money could buy. She knew she couldn’t get it running a roadhouse in Grand Forks, so she decided she’d build another establishment – the finest hotel in Dawson. The tiny frontier tent town had now, thanks to the lure of gold, become a thriving city of 30,000, and was struggling to become civilized.

Belinda ordered the best building supplies and fanciest furnishings from the outside. When they arrived by boat in Skagway, she made the rough trip over White Pass in order to supervise their delivery. She found them dumped alongside the trail, two miles out of Skagway. The teamster she had hired, Joe Brooks, had gotten a better offer from a whiskey dealer.

Furious, Belinda stormed into Skagway, to the docks, where she rounded up a gang of destitute men. She got them to fight among themselves, and named the winner her foreman. They caught up with Joe Brooks and his men, hauling the whiskey on pack mules up the trail. Her gang beat up Brooks’ foreman, dumped the whiskey, loaded Belinda’s goods on the mules, and went on to Dawson. Belinda headed up the procession, mounted on Brooks’ own pinto pony.

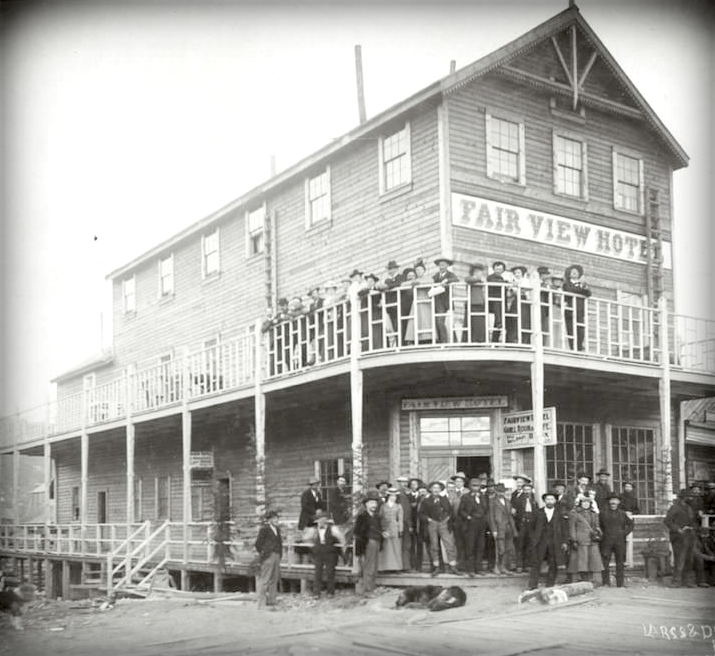

It took a full year to finish the hotel, but when it was done, the Fairview was, indeed, the finest establishment in town. It boasted 30 steam-heated rooms, brass beds, Turkish baths, a lavish dining room with a cut-glass chandelier, and a small orchestra that played chamber music in the lobby. It even had electric lights, powered by the engine of a yacht anchored in the harbor.

The only mundane feature of the hotel was its interior walls; because the limited supply of lumber in the area went mostly into building boats and sluices, the walls between the rooms were made of canvas. Even covered with classy wallpaper, they didn’t afford much privacy. Customers didn’t seem to care. In its first full day of operation, the Fairview took in over $6,000.

Not long after its construction, Belinda’s masterpiece was very nearly destroyed. In the spring of 1899, fire broke out in a saloon. Dawson had a fire department, but it was on strike, and the fire quickly spread. Volunteers melted the ice in the river and started pumping water, but the water froze in the hoses. The Northwest Mounted Police blew up Alex McDonald’s new office building in a vain effort to halt the fire’s progress. Flames licked at the walls of the Fairview. Townsmen beat at them with burlap bags soaked in mud puddles, and managed to limit the damage to the hotel. But 117 other buildings burned to the ground, and the lobby of the Fairview turned into a refugee shelter.

The town rose from the ashes – but not for long. That summer, word reached the Klondike of an even richer gold strike on the beaches of Nome, Alaska. By fall, gold-seekers were deserting Dawson in droves – 8,000 in one week alone. In their wake, big mining corporations moved in, with machinery that could dig out the gold that lay beyond the reach of the miners.

There wasn’t much call now for a first-class hotel. So Belinda took on a new challenge – as manager of the biggest mining company in the territory. The Gold Run Mining Co. was in sad shape, mainly because it also ran a roulette table and its employees were in the habit of stealing gold from the mines to gamble with.

Belinda’s first move was to throw out the gaming table and put a bridge table in its place. Within 18 months, the company was operating in the black again. She made other changes that were dictated less by her business sense than by her moral sense – banishing the women camp-followers, and banning smoking on the job. When an old sourdough defied the ban, she whistled to him, beckoned him over, and said, in her no-nonsense manner, “Get off this claim before nightfall.” This time, the miner obeyed.

Belinda was still only in her middle twenties, but she hadn’t had much time to think about marriage. In any case, the sort of men who were attracted to the Yukon didn’t attract her – until a dapper champagne salesman named Charles Eugene Carbonneau came to town. He had a valet, and he had a title – Count Carbonneau — and that undoubtedly spoke to Belinda’s craving for respectability.

Though a friend swore that he’d known Carbonneau in Montreal, and that he was in reality a no-count barber who was probably after her money, Belinda found him irresistible. In October of 1900, she accepted his proposal of marriage. They honeymooned in Paris, but were back in the Klondike in time to hear of a new gold strike, near the present city of Fairbanks. They, too, abandoned Dawson, and did well enough in the new boom town to buy a ranch near Yakima, Washington, in 1910, and build a stone castle on the property.

They continued to winter in Europe, where Carbonneau sank what was left of her fortune into a steamship company. It was a good enough investment – until World War I put an end to merchant shipping. They were wiped out.

Carbonneau became a purchasing agent for the Allies, and was killed by an enemy shell while on an inspection tour of the front lines. Belinda retired to their Washington ranch and their castle, but with no money coming in, she was eventually forced to sell the property.

Like Big Alex McDonald and nearly everyone else who sought or found a fortune in the gold fields, she ended her life with very little to show for it all – at least in terms of money. But in terms of experiences and indelible memories, she was still the richest woman of the Klondike.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply