The African Abolitionist who Championed Human Rights in Ireland

While Frederick Douglass is the most well-known and celebrated black abolitionist to visit Ireland, he was not he only one. Ireland was host to a number of black abolitionists, including a small number of women, who visited and lectured in Ireland between 1790 and the commencement of the American Civil War in 1861. Like Douglass, most commented on the ardency of the Irish abolition movement and the fact that they experienced no prejudice while in the country. One of the first black abolitionists to visit Ireland was Olaudah Equiano, who travelled to the country in 1791.

Equiano differed from later visiting abolitionists. He had been born in Africa and, as a young boy, along with his sister, had been captured and taken to America to be enslaved. The siblings never met again. During this process, Equiano’s name was changed to Gustavus Vassa. Also, Equiano belonged to the first generation of abolitionists who were campaigning at a time when the global slave trade was still in operation. It was assumed that if the slave trade were ended, enslavement would naturally atrophy. The trade was ended by Britain and America in 1807 and 1808, respectively. Enslavement, however, survived and extended its reach.

Equiano had been born in the Kingdom of Benin (now southern Nigeria) around 1745. He was captured when aged about 11, and taken to Virginia, but shortly afterwards was sold to a ship captain. During his time at sea, he travelled to Europe and visited England. Also, encouraged by an Irish man, he learned to read and write. His origins meant that, unlike the next generation of abolitionists who had been born into enslavement in America, Equiano had first-hand knowledge of the customs and traditions of Africa. He could also speak about the brutality of the “middle passage,” that is, the part of the trade in which Africans were placed in densely-packed ships and forcibly transported to the New World.

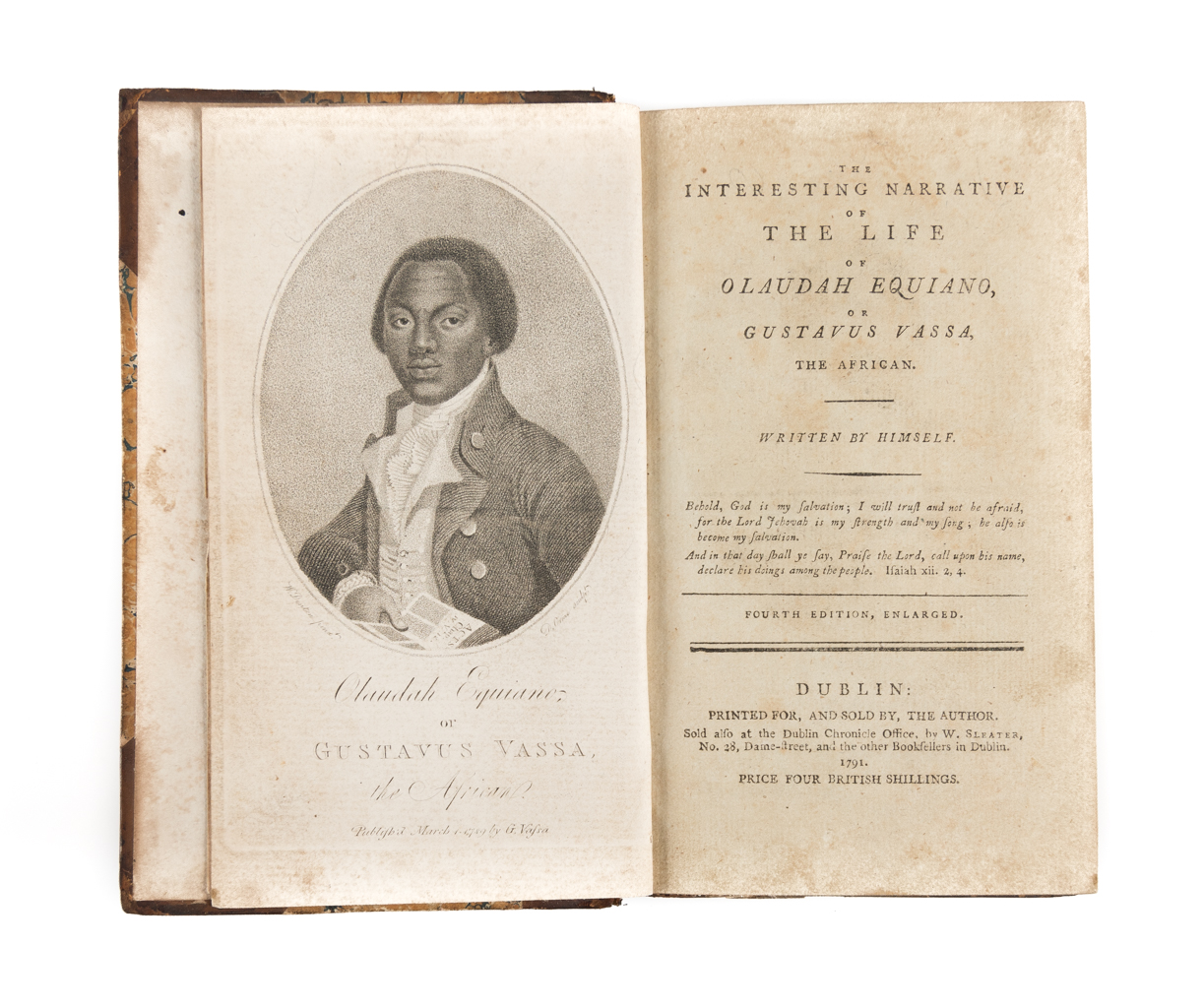

Unusually, Equiano, a very skilled sailor, was allowed a small income, and he was thus able to purchase his own freedom, which he did when aged only 20. He settled in London to avoid being recaptured and returned to slavery. In England, he worked in a variety of jobs. He also became involved in the movement to end the slave trade, then associated with William Wilberforce. Equiano attended debates in the British House of Commons and wrote letters to the press and to leading politicians. In this way, he became an influential figure in the abolition movement. His authority increased following the publication of his Narrative in 1789, which repeatedly sold out and went through nine editions (each enlarged) in less than ten years.

When Equiano travelled to Ireland in May 1791, he was regarded as a leading spokesperson on enslavement who was also a gifted writer and lecturer. He arrived in Ireland at a time of heightened revolutionary activity in Europe in the wake of the French Revolution of 1789. Within weeks of his arrival, Equiano would have witnessed the anniversary of the French revolution being celebrated on the streets of Dublin, both Irish Catholics and nationalists regarding it as a harbinger for liberty and the rights of man being extended to Ireland. His visit also coincided with the formation of the Society of the United Irishmen by Theobald Wolfe Tone. Many of the Society’s leaders were radical Protestants who urged an alliance with Catholics, and for both to unite under the common name of Irish men. At this stage, Ireland still had its own parliament in Dublin, but the United Irishmen wanted to completely end the colonial link with Britain and to establish an independent republic. It was members of this Society who hosted Equiano during most of his visit. Consequently, African-born Equiano, a former slave, unwittingly found himself at the centre of radical Irish politics.

In addition to wanting an Irish republic, the United Irishmen supported the more general concepts of liberty and democracy, which included the ending of slavery. Thomas Addis Emmet, one of the founders, described how black slaves and the Irish people were both subject to similar patronizing attitudes that depicted them as being incapable of freedom:

Some supposed—what had been asserted of the negro race—that the Irish were an inferior, semi-brutal people, incapable of managing the affairs of their country, and submitted, by the necessity of their nature, to some superior power, from whose interference and strength they must exclusively derive their domestic tranquility.

Given their stance on the issue of enslavement, it is not surprising that Equiano comfortably interacted with members of the United Irishmen. And he clearly impressed his hosts, Thomas Digges describing Equiano as:

an enlightened African, of good sense, agreeable manners, and of an excellent character and who … was torn from his relatives and country (by the more savage white men of England) at an early period in life.

In Belfast, Equiano stayed with the family of Samuel Neilson, one of the most radical of the United Irishmen. Neilson’s home was a hub of political activity and, inevitably, while there, Equiano would have met other leading United Irishmen. Neilson was also editor of the bi-weekly Northern Star newspaper, which first appeared on 4 January 1792, when Equiano was still a guest in his home. The paper’s tagline was, “Unite and be Free—Divide and be Slaves.” To show their support for abolition, readers were urged not to consume West Indian produce, especially rum and sugar, describing its consumption as “positive and downright murder.”

Equiano left Ireland at the end of January 1792. The day before, a large meeting had been held in Belfast to demand Catholic Emancipation. It is probable that Equiano attended as two of the main speakers were Henry Joy McCracken and Neilson. The parallels with slavery and the movement to end the slave trade would not have been lost on him. In a later edition of his Narrative Equiano briefly referred to his time in Ireland, writing:

I shall only observe in general, that, in May 1791, I sailed from Liverpool to Dublin where I was very kindly received, and from thence to Cork, and then travelled over many counties in Ireland. I was everywhere exceedingly well treated, by persons of all ranks. I found the people extremely hospitable, particularly in Belfast, where I took my passage, on board of a vessel for Clyde, on the 29th of January, and arrived at Greenock on the 30th.

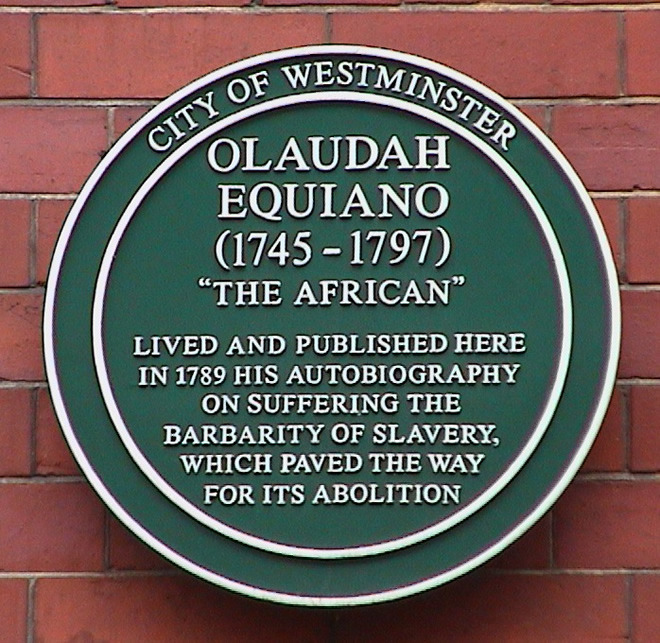

Back in Britain, Equiano continued to agitate publicly for the ending of the slave trade. He also became involved with London Corresponding Society, a progressive group that wanted a reform of parliament and for the vote to be extended to all men. The British government, now at war with France, was worried by the growth of radical movements in Ireland and Britain. In 1794, both the Corresponding Society and the Society of United Irishmen were declared illegal, and their members accused of High Treason. Several leaders were arrested, while others went into hiding. Equiano’s public profile and links with radical groups on both sides of the Irish Sea made him particularly vulnerable to arrest. At this stage, he disappeared from view. Equiano did not reappear until his death in London in March 1797. He was aged 52. His burial place remains unknown.

Equiano did not live long enough to see the abolition of the slave trade—that would take another ten years to achieve. Nonetheless, his contribution to its ending had been immense. Equiano was in the vanguard of the first wave of abolitionists who campaigned tirelessly to end the trade and win over public opinion. Almost uniquely, he could speak of the horrors of enslavement from first-hand experience. Unwittingly also, Equiano forged a path that would be followed by later black abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and others, by writing a narrative of his life and by lecturing throughout Ireland and Britain. Individually and collectively, these abolitionist visitors challenged negative stereotypes about black people.

Today, Equiano is largely forgotten in Ireland, although in Britain he has been commemorated for his role in the abolition movement. But Equiano was more than an abolitionist—his involvement with the United Irishmen and other radical groups marked him as an early champion of international human rights. He deserves to be more widely remembered.

Christine Kinealy’s Black Abolitionists in Ireland has just been published by Routledge. It examines ten abolitionists—nine men and one woman—who visited Ireland between 1791 and 1860.

Christine is the Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University, and is the author of many books and articles on famines in Ireland. Her current research looks at the experience of black abolitionists who visited Ireland.

Christine is the Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University, and is the author of many books and articles on famines in Ireland. Her current research looks at the experience of black abolitionists who visited Ireland.

Please see the above website.

a PDF 2020 version of his book THE INTERESTING NARRATIVE can be downloaded for FREE

A very interesting article about a great man. I can only add that Equiano was buried in Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, London Borough of Hackney. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/161357969