“Whatever the future may hold, wherever it may take us, we can bring along only what we possess, and if we don’t possess our past, if instead of a true history and a significant literature, we bring along only trivia, empty myths and a handful of stories, or-worst of all — the latest intellectually fashionable versions of ourselves, we will offer those to come after nothing of lasting consequence.”

“Perhaps the history of Irish Americans that will be written at the end of the 21st century will be entitled “How the Irish Became Brown.” What a wonderful prospect . . . What a welcomed fate. . The Irish as the common denominator of a new American construct . . .”

The unique American subculture that the Irish created in the wake of the Famine — the culture I grew up in — a culture that cohered around the Catholic church and the Democratic party, with a working-class base and widespread aspirations to lace-curtain propriety, a culture deeply skeptical about WASP institutions and pretensions, and suspicious and resentful of the mainline tradition of Protestant moral reform and economic self-determination-is dead and gone. It’s with Ed Flynn or Tom Prendergast — take your piety of big-city Democratic bosses of a generation or so ago — in the grave. It lingers in some pockets, for sure, and survives in the formative experiences of pre-Vatican II Irish-Catholic fossils like myself. But it’s as doomed as the dodo and no amount of humpty-dumpty yearning for the way things were — or the way some like to imagine they were — will bring it back.

Today, it’s almost impossible to recapture how distinct and apart that world was, how foreign Anglo-Protestant America seemed, how certain we were of our distinct identity and special destiny. We were a parochial people literally and figuratively. In the place I grew up, our basic compass was the parish we were from. That’s how we identified ourselves: I’m from St. Raymond’s or St. Helena’s or Sacred Heart or Tolentine or whatever.” And we were parochial in the sense of being intellectually narrow-minded and constricted.

That narrow-mindedness has often been commented on, and often, I think, in a wrong-headed way. The adults I knew were avid devourers of books. They enjoyed the theater. They reveled in the pace and variety of urban life, a pace and variety the Irish had in fact helped create. They held high educational ambitions for their children. Almost everyone I knew was wildly addicted to movies, and many of us availed ourselves of the legion or decency’s rating system, where the C-or “condemned” list conveniently underlined what was really worth seeing.

The fundamental narrow-mindedness we suffered from wasn’t so much in our attitude to the world as to ourselves. We wanted — we demanded — to be seen in one light and one light only. I remember seeing The Bells of St Mary’s on television around the same time that my aunt took me to one of those periodic theatrical re-releases of The Wizard of Oz. Although I sensed it at that moment, it would he some time later before I could articulate the feet that the relationship between the parish presided over by Monsignor Barry Fitzgerald and his crooning curate father Bing Crosby and the real-life parish I lived in was the reverse of what existed between the Emerald City and Dorothy’s Kansas.

The ecclesiastical Oz of the Reverends Fitzgerald and Crosby was populated with characters who bore some resemblance to people I knew first-hand. But on screen the ironic, tough-minded, combative, argumentative, believing, suspicious, hard-drinking, back-biting, funny, obnoxiously profane, relentlessly skeptical, gloriously complicated people I knew — people as contradictory as any cowardly lion and as rnanipulative as the Wizard himself-became as tame and predictable as Auntie Em’s Kansas farmhands.

This, of course, was the nihil-obstat version that everyone in the parish applauded. All the adults I knew loved The Bells of St.Mary’s, even the ones who never stopped badmouthing the clergy and couldn’t say enough bad things about the licking they’d taken in parochial schools. This was how we wanted the world to see us, America’s best-behaved ethnic group, a big-screen refutation of the lies once spread by nativists. The stage Irishman was okay as long as he looked and acted like Bing Crosby and, hell, if the stage Irishwoman wasn’t only a nun but a nun played by Ingrid Bergman with a Swedish accent, well, Hooray for Hollywood.

The Irish in America — at least the Irish I grew up with — were still in the defensive crouch they’d arrived in during the Famine, still sensitive to the distrust and dislike of real America, to the suspicions about our loyalty and supposed proclivity to raucous misbehavior. We were forever reminding ourselves — and the rest of America — of how many Irish fought with Washington, how many died at Antietam, and how many won the Congressional Medal of Honor, a litany of self-justification that implicitly accepted it wasn’t enough we’d been here for over a century . . . that we still had a right to stay.

Even J.F.K.’s election as president didn’t entirely settle the matter. Writing in 1965, in his one-volume Oxford History of the American People, Samuel Eliot Morison could dismiss the Famine Irish as having added, quote, “surprisingly little to American economic life, and almost nothing to American intellectual life.” The good news, I suppose, is that Morison used the word “surprisingly,” the bad news: as far as he was concerned, this was pretty much the high point of the Irish-Catholic role in America. From there, it was backward and downward to Tammany Hall and the corruption of American urban politics.

It’s in this light that I’m particularly amused to read the currently popular bedtime tale How the Irish Became White. Here the old nativist canard that the Irish can never shed their essential foreignness, that they are a race of eternal strangers, that their attempt to become true Americans is intrinsically futile, is turned on its head. Yes, the Irish still fail. In the eyes of some, the Irish will always fail. But now they fail upwards. It’s not that they weren’t American enough, but too American, immigrant Esau’s who traded their birthright of Irish resistance to oppression for the American pottage of material success.

If there’s any central theme to the story of the Irish in America, it isn’t, in my opinion, how they became white, but how they stayed Irish: that is, how an immigrant group already under punishing cultural and economic pressures, reeling in the wake of the worst catastrophe to take place in Western Europe in the 19th century, a people not only devoid of urban experience but largely unacquainted with the town life prevalent throughout the British Isles, suddenly finding itself plunged into the fastest industrializing society in the world, regrouped as quickly as it did; built its own far-flung network of charitable and educational institutions; preserved its own identity, and had a profound influence on the future of both the country it left and the one it came to.

It was done imperfectly, for sure, and was marred by sins and stupidity, by mistakes and missed opportunities, but for me; the wonder is that it was done at all.

In general, I’m always suspicious about the search for single themes and unified theories that provide neatly apprehensible explanations for human behavior. As the historian Barbara Fields has written in an essay entitled “Ideology and Race in American History,” “Each new stage in the unfolding of the historical process offers a new vantage point from which to seek out those moments of decision in the past that have prepared the way for the latest (provisional) outcome. It is the circumstances under which men and women made those decisions that ought to concern historians, not the quest for a central theme that will permit us to deduce the decisions without troubling ourselves over the circumstances.”

In the specific case of Irish Americans, the notion of definitively deciphering their history with the Rosetta stone of race at least provides the basis for a polar interpretation to the one enshrined in The Bells of St Mary’s. Next door to the idyllic never-never land of cinematic fantasy, there is now the mirror-image community of uniformly abusive nuns, ogre-like priests, parish after parish of solidly united bigots determined to get what they could for themselves by becoming active collaborators and supporters of the American system of racial exclusion and exploitation.

What’s mostly lacking, I feel, is the saving grace that art can bring to the saga of any family or ethnic group or country, to unearthing the rich contradictions of Irish America, to delineating the bewildering, destructive, exhilarating journey between what were once not so much different cultures as different universes, to exposing the levels of struggle and failure, self-doubt and self-hatred, penetrating wit and indelible grievance, paralyzing depression and deep, resonant laughter.

I don’t want to sound as though I’m entirely dismissing the role of history in this process of self-examination and reclamation. At its best, in books like Bob Scally’s The End of Hidden Ireland, history can reach past the faceless, sexless sanitation of generalities and statistics to touch the lives of those now dead, to give us a sense of the density and intensity of every human life, and even to allow the poor and powerless a dignity that they were denied in their own lifetimes.

Recently, I stumbled across a small jewel of historical detective work that recounts the history of a case tried in the New York Surrogate’s Court, in 1932. The Recluse of Herald Square, written thirty-five years ago by Joseph Cox, presents the story of Mrs. Ida Mayfield Wood who, along with her sister, spent a quarter of a century hiding in a hotel room. When her sister died and the police were called they discovered that amid the clutter and debris of her room, Mrs. Wood had nearly a million dollars in cash and bonds. This was at the bottom of the worst depression in American history. As well as her hidden treasure, Mrs. Wood had another secret, one that it would take dozens of lawyers, investigators and would-be heirs to unravel, Without entirely ruining the mystery for those who might want to read the book, I’ll simply point out that Mrs. Wood’s secret casts a good deal of light on the status of the Irish in mid-19th century America and on a desire for “passing” that wasn’t restricted to racial disguise.

As a lapsed historian, however, I don’t feel qualified to stand in public and pass judgement on the practices of a priesthood I’m no longer part of. I continue to pray that at the hour of my death, I’ll be attended by a historian — preferably from a Catholic institution — who’ll receive me back into the fold. Meantime, I continue to enjoy the happy, carefree life of the apostate, unburdened of a historian’s scrupulosity, willingly giving in to every temptation to speculate and invent, to avoid the virtuous work of analysis and indulge in the pleasures of anecdote.

For instance, I remember my father — a remarkable, difficult usually inaccessible man — on the triumphal night John Kennedy was elected president, the same night as my father was elected to the State Supreme Court, the fourteenth and last time he ran for office, this grandson of Famine emigrants, well-oiled and declaiming to the swaying crowd in our Bronx living room, “Well, now, Mr. Nixon, you can kiss our royal Irish ass!”

Beautiful, lofty things . . . a thing never known again.

In fiction Elizabeth Cullinan has captured that world, I think, and Alice McDermott and William Kennedy. Mostly, it remains enshrouded and unrevealed, pretty much entirely absent from the dominant form of American cultural self-examination — the movies. A story central to the making of the American identity, it has yet to be explicated and celebrated as fully as it should be. Perhaps it will never be.

Yes, then, Irish America is rich, successful, influential — fat and happy with its lists of successful entrepreneurs and zillionaires. We’re headed somewhere, that’s for sure. The momentum of the journey is increasingly weighted toward the American part of the Irish-American equation, which is why we came here in the first place. Anyone who has the courage to predict where it will end has more courage than I do — or less fear of being exposed as an idiot. But to paraphrase Captain Kirk, “as we boldly go where no Irishman or woman has ever gone before,” I hope, as Sydney Carton hoped, “it is a far, far better place than we have ever gone before.”

Let me suggest one possibility.

About a year ago, the New York Times Sunday Magazine ran a double page of photographs of American girls and boys whose multi-ethnic, multi-racial background defied any easy characterization — a level of mongrelization that is continuing to gather steam, to the consternation of racial purists of various persuasions. The most common identity shared in this depiction of ethnic fusion — which may one-day rise to the level of a racial meltdown — was Irish. Perhaps, then, the history of Irish Americans that will be written at the end of the 21st century will be entitled “How the Irish Became Brown.” What a wonderful prospect . . . What a welcomed fate. . The Irish as the common denominator of a new American construct . . . the Irish as gravediggers for that last and most enduring of all 19th century superstitions — scientific racism.

Whatever the future may hold, wherever it may take us, we can bring along only what we possess, and if we don’t possess our past, if instead of a true history and a significant literature, we bring along only trivia, empty myths and a handful of stories, or-worst of all — the latest intellectually fashionable versions of ourselves, we will offer those to come after nothing of lasting consequence.

A long time ago, in a bar called The Bells of Hell, while I was in the embryonic phase of thinking about writing a novel about the Famine Irish in New York and was unsure whether there was a story worth telling – and where better to worry over an unborn novel than in a place named The Bells of Hell? — I heard the late Kevin Sullivan-ex-Jesuit, scholar of Irish literature and raconteur-recite Paddy Kavanaugh’s poem “Epic.”

It stayed with me across the years. It sustained me and still does. I’ve always found in it the anti-toxin to the Irish-American original sin of self-doubt.

The poem goes like this:

I have lived in important places, times

when great events were decided, who owned

that half a road of rock, a no-man’s land

surrounded by our pitchfork-armed claims.

I heard the Duffys shouting ‘damn your soul’

And old McCabe stripped to the waist, seen

Step the plot defying blue cast-steel —

‘here is the march along these iron stones’

that was the year of the Munich bother. Which

was more important? I inclined

to lose my faith in Ballyrush and Gortin

till Homer’s ghost came home whispering to my mind

he said: I made the Iliad from such

a local row. Gods make their own importance.”

Today, Irish America is powerful enough and wealthy enough to decide for itself where it’s headed and what it will take on the journey. Wherever we may end up, suburbs or city, the south end of Jersey or the outer end of the galaxy, it is we the living who will choose what will be recorded, remembered, redeemed from silence and oblivion by scholarship and art Gods make their own importance.

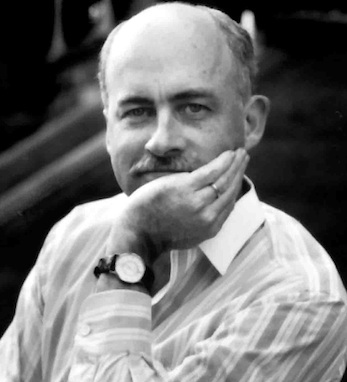

Peter Quinn is the author of Banished Children of Eve a historical novel based on the famine Irish in New York, and many other novels. He was also a speechwriter who worked for two democratic governors of New York. Quinn was a participant in the Ernie O’Malley Lecture series “Locating Irish America at the Millennium,” which to place at NYU in December 1999. The above is an edited version of his presentation.

Peter Quinn is the author of Banished Children of Eve a historical novel based on the famine Irish in New York, and many other novels. He was also a speechwriter who worked for two democratic governors of New York. Quinn was a participant in the Ernie O’Malley Lecture series “Locating Irish America at the Millennium,” which to place at NYU in December 1999. The above is an edited version of his presentation.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the April / May 2000 issue of Irish America.

Mr. Quinn: A small quibble. You’ve got the somewhat infamous Kansas City Irish political “boss” down as Tom Prendergast. His name was “Pendergast” and I know that well from having looked into him. That’s because he had the image as somewhat of a crook and, over my lifetime, a lot of people have asked me if I’m related!

Admittedly, our prototype namesake was the Cambro-Norman Maurice who spelled it “dePrendergast.” Like most Anglicised Irish names, both “real” Irish and Norman, the spelling has been quite a variable and optional thing. In Tom’s case, someone back up his line dropped the first “R”, but there’s a LOT of other variations as well.

Minor quibble, good article!

W.J. PRendergast

Portland, OR