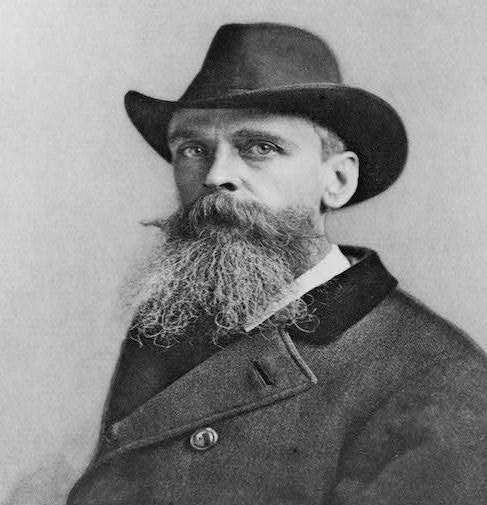

Each year, 3.5 million visitors flock to Yellowstone National Park, the world’s first national park. Although Yellowstone is world famous, the story of Thomas Moran, the Irish American landscape painter, whom some call ” the Founding Father of the National Parks,” is not.

When Dublin-born Thomas Moran Sr. arrived in Philadelphia with his family from Bolton, England in 1844, he could never have imagined that his son Thomas Jr. would be hailed as one of America’s greatest artists, nor that his son’s paintings would one day hang in the White House or in the Capitol.

Because of the Moran’s poverty, Thomas Jr. needed a trade to help the family make ends meet. His father apprenticed him to an engraver, but the future artist found the work boring and instead spent a great deal of his time sketching. When the owner of the engraving shop saw the quality of his drawings, he realized that Moran’s sketches were much more valuable than his engravings. Moran steadily improved his sketches, which soon looked highly professional. He also began to paint watercolors, which the shop owner sold for handsome sums. Bored by the tedious subjects he was asked to draw, Moran soon left his apprenticeship to become an artist together with his brother Edward.

A Belfast-Born Painter Guides Moran

The brothers opened up a studio, but they knew little about painting. However, they had the good fortune to live besides one of Philadelphia’s top artists, Belfast-born James Hamilton, who began to show the Moran brothers the finer aspects of painting. Hamilton encouraged the brothers to read the English art critic, and painter John Ruskin who advised aspiring artists to capture the impressions that nature made upon the them, rather than trying to copy it. Perhaps Hamilton’s greatest impact, though was in introducing them to the works of the great English landscape artist J.W. Turner whose reproductions hung in Hamilton’s studio. Moran later said that he owed to Hamilton, “the direction and character that afterwards marked his works.”

Although Hamilton influenced Moran, the Belfast painter never formally taught him and Moran was largely self-taught. He later said,” You can’t teach an artist much how to paint… I used to think it was teachable, but I have come to feel that there is an ability to see nature and unless it is within the man, is useless to impart it.” Following Ruskin’s advice, Moran spent many hours along the banks of the Schuykill and Wissahickon rivers sketching the natural scenery and then returning to his studio to paint the scenes on canvas.

In the 1850s, painters were much in demand and could earn a good living. Moran, who was extremely well-read, especially in poetry, created a number of popular canvases portraying scenes from famous poems often set in the American wilderness.

His first great canvas he painted at nineteen, inspired by the Percy Shelley poem Alasstor, about a melancholy poet traveling through the awful ruins of the days of old. The painting was later chosen to hang in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts yearly exhibition, helping to establish Moran’s reputation.

With money earned from painting, Moran and his brother set off in 1862 for England, to study the paintings of J.W. Turner. Moran spent months at the National Gallery studying Turner’s landscapes and glowing colors. After months of studying Turner’s works, Moran came to the conclusion that Turner’s landscapes were not exact transcriptions of nature. Turner looked at nature merely as a medium for a good picture. Turner’s most lasting influence on Moran was his unique sunlight illuminating his canvases, which Moran tried to replicate in his paintings.

Being in England made Moran realize how thoroughly American he was and how he missed Pennsylvania’s scenery. He later said “I decided very early that I would be an American painter. I will paint as an American, an American only.” He also longed to return to the states because he had fallen in love with a teenager, Scottish born Mary Nimmo whom Moran would marry in 1863 and whose support was instrumental in Moran’s success as an artist.

A Turning Point

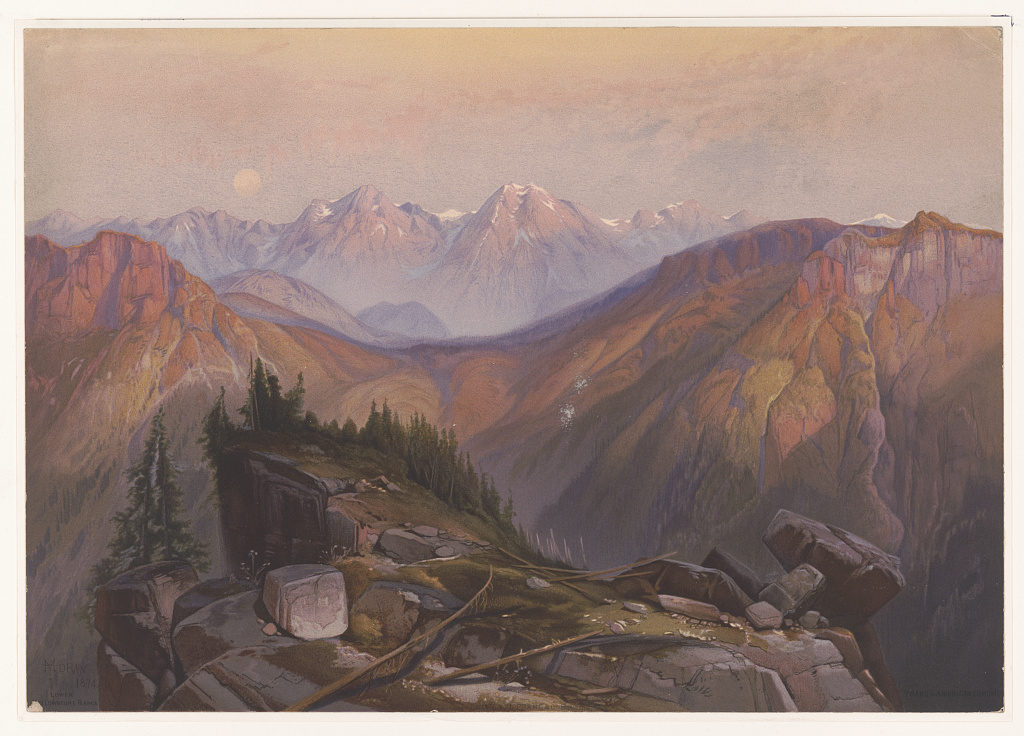

Moran achieved limited success in the 1860s, but his big breakthrough came in 1871 when Dr. Ferdinand Hayden, director of the United States Geological Survey, invited him on his expedition into the unknown Yellowstone region. Moran agreed to join, despite never having ridden a horse before the arduous trek. During forty days in the wilderness area, Moran was astonished by Yellowstone’s natural wonders, thirty of which he visually documented. Moran was accompanied by photographer William Henry Jackson and for more than six weeks they selected the best subjects and points of view for photographs, watercolors and sketches.

Moran realized that Americans were fascinated by the mysterious landscapes of the American west and that an artist who captured it would become popular and wealthy. The most celebrated artist of the day was another landscape painter Albert Bierstadt, who had been exhibiting large-scale paintings of the Rocky Mountains and Yosemite for more than a decade. Moran realized that if he captured the unique scenery of Yellowstone, he could challenge Bierstadt as America’s foremost landscape painter.

Like his idol Turner, Moran did not merely record Yellowstone’s natural beauty, rather he used it as a departure point to produce stunning canvases that captured the area’s scenery, but also slightly altered it, adding his own unique compositional sense and coloration. Dr. Hayden, seeing Moran’s Yellowstone paintings said, “their greatest interest does not lie in their subject matter so much as in the artist’s own qualities which they display. The prevailing characteristic of the sketches is not, as might have been expected, boldness or brilliancy, but extreme delicacy.”

Moran determined to lay claim to Yellowstone as its visual interpreter. A Reporter from The Helena Herald interviewed Moran and told his readers, “Mr. Moran pronounced the country the most wonderful region on the Continent. All the phenomena which elsewhere is found scattered and distributed over widely separated portions of the globe, is here crowded into a region which does not exceed eighty miles in length.”

Moran soon returned east and quickly became his own best publicist. He claimed that he had created “the most remarkable portfolio, perhaps, that it has ever fallen to the lot of an artist to fill. He quickly set to work on a giant canvas to capture its most dramatic area. When Dr. Hayden and his party returned to Washington, he presented Moran’s sketches and Jackson’s photographs to members of Congress, hoping to prod Congress to approve the creation of America’s first national park. Doubts about Yellowstone’s natural wonders rapidly vanished thanks to Moran and Jackson’s stunning images. Jackson admitted that, as Congress considered creating the park over the winter of 1871-1872, the watercolors and photographs made during the survey “were the most important exhibits brought before the [Congressional] Committee.” The “wonderful coloring” of Moran’s sketches, he wrote, made all the difference.

Only seven months after Moran’s work on the Hayden Survey finished, an amazingly short period of time, Yellowstone National Park had become the first national park in the United States and, it is widely held, the first national park in the world.

Three months later, Moran completed the monumental 7′ x 12′ panoramic, “Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone,” which was purchased by the Congress for the huge sum of $10,000 to display in the Senate lobby, causing a noted art critic to call it “the only good picture to be found in the Capitol.” By this time, friends had started to call him “Tom ‘Yellowstone’ Moran,” and he had begun putting a “Y” into his initials when signing his works!

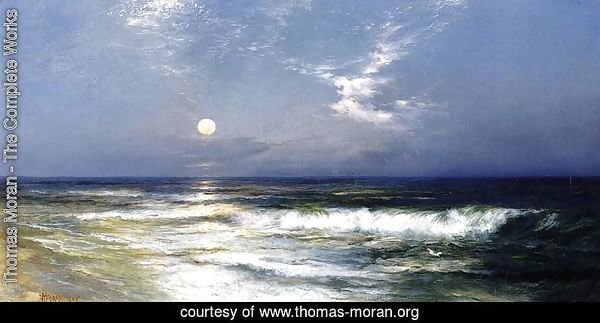

Moran continued to travel back to the area for many years. In 1895, he created “The Three Tetons,” which now hangs in The White House in Washington D.C. Moran was particularly struck by the beauty of Wyoming’s Green River and he produced a number of highly popular Green River canvases during his lifetime. Moran family lore claims that his daughter used to say, “whenever we needed money, papa painted another Green River.”

By the time of Moran’s death in 1926, he had painted a dozen other areas that would also become national parks or monuments, but he loved Yellowstone most of all and its creation is part of Moran’s enduring legacy.

Geoffrey Cobb is a teacher of social studies and English as a second language at the High School for Service and Learning in Flatbush, Brooklyn. He has written three books on Brooklyn history as well as articles for Irish America, The New York Irish History Roundtable and the Irish Echo.

Geoffrey Cobb is a teacher of social studies and English as a second language at the High School for Service and Learning in Flatbush, Brooklyn. He has written three books on Brooklyn history as well as articles for Irish America, The New York Irish History Roundtable and the Irish Echo.

Leave a Reply