By Christine Kinealy

Historian Christine Kinealy is documenting black abolitionists who visited Ireland, including singer Paul Robeson, abolitionist Frederick Douglas, and Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield. Born into slavery, Elizabeth became known in her life-time as the Black Swan who broke down barriers where ever she sang, and who, like Robeson and Douglas, had a special place in her heart for Ireland.

In the 19th century, Ireland provided a safe haven to many former slaves who were fleeing from the punitive Fugitive Slave Acts. Some came to win support for the abolitionist movement by giving a first-hand account of the horrors of slavery. The most famous of these exiles was Frederick Douglass. In 1845, aged 27, he came to Ireland as a fugitive slave, intending to stay for only a few days. The warmth of the welcome meant that he stayed for four months. In Ireland, and for the first time in his life, Douglass admitted that he felt “like a man and not a thing.” Douglass, who went on to be a champion of international human rights, never forgot Ireland, and Ireland never forgot him.

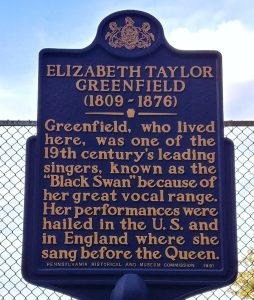

Other Black abolitionists who visited Ireland are less well remembered and a number have disappeared off the historical record. Women, in particular, have tended to be invisible. One such person who came to Ireland, sang before thousands to great acclaim, but is now largely forgotten, is Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, known in her life-time as the Black Swan.

Elizabeth was born into slavery in Natchez, Mississippi, around 1820 – like other enslaved people, she never knew her birth date. Her father was “a full African,” while “white and Indian blood flowed in her mother’s veins.” Elizabeth Greenfield was the name of her female owner. The older Greenfield moved to Philadelphia when Elizabeth was a child and joined the Society of Friends. She also freed her slaves. Young Elizabeth remained with her, eventually becoming her companion. On Greenfield’s death in 1844, she left a considerable fortune to Elizabeth, but the will was contested and she never received it.

As a young woman, Elizabeth knew she wanted to be a singer and she could afford to pay for lessons, but no professor would accept a Black pupil. Following a performance before the Buffalo Musical Association, Elizabeth was persuaded to give public performances. She was immediately dubbed the “Black Swan” by the press, which was a play on two other famous female opera singers: Jenny Lind, the “Swedish Nightingale,” and Limerick-born Catherine Hayes, “the Swan of Erin.” The name, the Black Swan, stuck.

In 1851, Greenfield embarked on a national tour of the “free states” in America and eastern Canada. This was a particularly sensitive time in Antebellum politics as a new and more draconian Fugitive Slave Act had been passed in 1850, leading thousands of runaway slaves to flee to Canada. Moreover, Elizabeth’s repertoire ranged from opera arias to parlour songs – music generally reserved for White artists. At this stage, African American music was looked down on as being primitive, it being viciously parodied in popular minstrel shows. In contrast, Frederick Douglass, himself a talented musician, had likened the songs of the slave plantations to Irish music because of the plaintiveness and haunting qualities of both. Douglass also understood that music was a powerful tool of subversion by oppressed people.

The Black Swan became an instant singing sensation, performing before packed audiences wherever she went. Despite her talent, especially her range and her power, several critics described her voice as being unpolished and requiring cultivation, a reference to the fact she was self-taught and, implicitly, black. The pro-slavery New York Herald was particularly offensive, describing Greenfield’s performance as ‘the best joke of the season’ and likening her to a “biped hippopotamus.” Among African Americans, she also became controversial because, if they were allowed into the theatres (and this was not always the case), they were segregated from the rest of the audience. Elizabeth addressed this situation by appearing for free in Black churches.

It was probably with some relief that, in April 1853, Greenfield sailed for the United Kingdom. Before departing from New York, she had hoped to attend an opera in the Niblo Gardens on Broadway, but she was refused admission.

Even before arriving in Britain, Elizabeth’s celebrity had spread across the Atlantic. Her arrival in Liverpool was widely noted. One Irish newspaper commented, “Among the passengers by the Asia is Miss Greenfield, the ‘Black Swan,’ a songstress rivaling Miss C. Hayes and Jenny Lind.”

In London, Elizabeth met Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of the best-selling Uncle Tom’s Cabin (the first American novel to sell more than one million copies), who was on her own promotional tour. Stowe became a patron the young singer, describing her as “gentle, amiable, and interesting” and her voice as “a most magnificent tenor.” Like other white women who took an interest in Elizabeth, Stowe advised the young singer to always with be modest and genteel, so as not to cause offence. Stowe also introduced Elizabeth to the novelist, Anna Maria Hall, author of the Irish Sketches, who was similarly entranced.

In August 1853, the Black Swan travelled to Ireland. Even before she landed in Dublin, newspapers had been reporting on her activities in London and her remarkable voice. In Dublin, Elizabeth took part in a series of performances in the Rotunda Rooms, at the top of what is now O’Connell Street. The Rotunda Rooms, which adjoined the famous maternity hospital, were among Dublin’s earliest concert and music halls, opening in 1757. The noted architect, James Gandon, had designed the beautiful Square Entrance Building. It was a prestigious venue that could accommodate up to 2,000 people. Elizabeth’s accommodation was similarly high-class; she stayed in the fashionable Shelbourne Hotel. Within the United States, it was doubtful that she would have been allowed to enter such buildings.

Although accompanied by three British opera singers, who were already known to Irish audiences, Elizabeth was the headline act in a series of 12 performances described as the “Black Swan Concerts.” The newspapers were fulsome in their praise. The Freeman’s Journal described her as a “self-taught musical genius,” while another article referred to her as “one of the vocal wonders of our time.” One paper referred to her as “this famed negro vocalist;” otherwise, her race was rarely commented on – the Cork Examiner described her simply as “the American vocalist.” Overall, there was little evidence of the racialized language that was so often present in the American press.

Not all of the concerts were sold out, but in general attendance was described as “most numerous” and “fashionable.” One evening, the audience included, “some of the leading and distinguished musical professors of Dublin, whose presence on the occasion illustrated the high estimation in which Miss Greenfield is held in high places.”

When performing in Dublin, Elizabeth featured a number of Irish songs, including “The Last Rose of Summer” by Thomas Moore, and “Erin is my home,” an Irish American song of uncertain lineage. It seemed, however, that Irish audiences preferred to hear American songs. The Freeman’s Journal, in praising her rendition of the popular American folk song, “Home Sweet Home.” explained that it gave a:

striking indication of the success which she would achieve in the rendering of the simple melodies illustrative of negro life, and which would derive a double charm by being sung by this gifted vocalist, whose knowledge of and sympathy with her oppressed race would give an inexpressible charm to the songs of the Ohio and the Mississippi.

Elizabeth’s song choices were significant. Although she did not speak publicly of slavery or abolition when in Ireland, she included a number of songs that dealt with the subject of slavery directly. These included, “The vision of the negro slave,” which dealt with the cruelty of the system:

Elizabeth’s song choices were significant. Although she did not speak publicly of slavery or abolition when in Ireland, she included a number of songs that dealt with the subject of slavery directly. These included, “The vision of the negro slave,” which dealt with the cruelty of the system:

Tortured to death by lash-inflicted wound;

His head bowed down and sunk upon the ground ….

She also sang a song penned for her by an English composer about the pain of being a female slave, titled, “I am free.” Significantly, Elizabeth had never sung any abolitionist songs when touring in America. Her deliberate and public references to slavery while she was in Dublin suggest the importance of Ireland as a safe place for Black abolitionists to criticize slavery. Like Douglass a few years earlier in Ireland, Elizabeth was able to appreciate what freedom really meant.

In mid-August, Elizabeth and the company travelled to Cork to perform. The manager of the Cork Theatre announced in the papers that he had secured their services “at immense expense.” A special late-night train and a steamer to Queenstown was commissioned to allow people to attend from outside of the city. Tickets ranged from one shilling to three shillings each, which was well out of reach for most people.

The final Black Swan concert in Dublin was on August 22. Although the rest of the company then left Ireland, Elizabeth stayed on to give two solo farewell performances. She was accompanied by a military band.

In September, Elizabeth returned to London where she continued to perform private concerts, usually under distinguished patronage. She then toured Britain for almost a year. In May 1854, she sang in front of Queen Victoria, in honor of the monarch’s 35th birthday. Elizabeth was paid £20 for this performance.

Following her return to America, Elizabeth combined public performances with charity work. During the Civil War, she performed at abolitionist and recruitment rallies, appearing alongside Douglass on several occasions. Elizabeth also continued to do charitable work for aged and orphaned African Americans. She died at her home in Philadelphia on 31 March 1876.

Elizabeth Greenfield has been described as “America’s first Black pop star.” She was much more. Elizabeth used her talent to confront the stereotypes that abounded in society and in the popular minstrel shows about what it meant to be a Black performer. By doing so, she transgressed boundaries of race, artistry, class and gender, occupying a unique place that was part of American mainstream culture, while simultaneously defying and re-defining it. Elizabeth’s time overseas, and the warmth of her reception, challenged White audiences in America who could not accept Black people as equals. Her forgotten time in Ireland, where Elizabeth used her very special gifts to criticize slavery, is part of her remarkable story.

Be sure to watch the INTERVIEW WITH DR. KINEALY created by the Irish Heritage Trust and National Famine Museum.

Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield: The Abolitionist “Black Swan” was created by the Irish Heritage Trust and National Famine Museum, Strokestown Park in collaboration with the African American Irish Diaspora Network and Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University. It is funded by the Government of Ireland Emigrant Support Programme. Please take a moment to respond to our audience survey below: https://forms.gle/qah6Pyjehqs5a7sW7

Dr. Christine Kinealy, Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University, is author of many books and articles on famines in Ireland. Her current research looks at the experience of black abolitionists who visited Ireland. In 2018, her book, Frederick Douglass and Ireland: In His Own Words’ (Routledge, 2018, 2 vols), was published.

Dr. Christine Kinealy, Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University, is author of many books and articles on famines in Ireland. Her current research looks at the experience of black abolitionists who visited Ireland. In 2018, her book, Frederick Douglass and Ireland: In His Own Words’ (Routledge, 2018, 2 vols), was published.

Kinealy’s latest book Black Abolitionists in Ireland is now available on Amazon, Google Play Books and at Barnes and Noble.

I found this article very interesting. The thorough description and details about the “Black Swan” was moving☘️