By Ray Cavanaugh

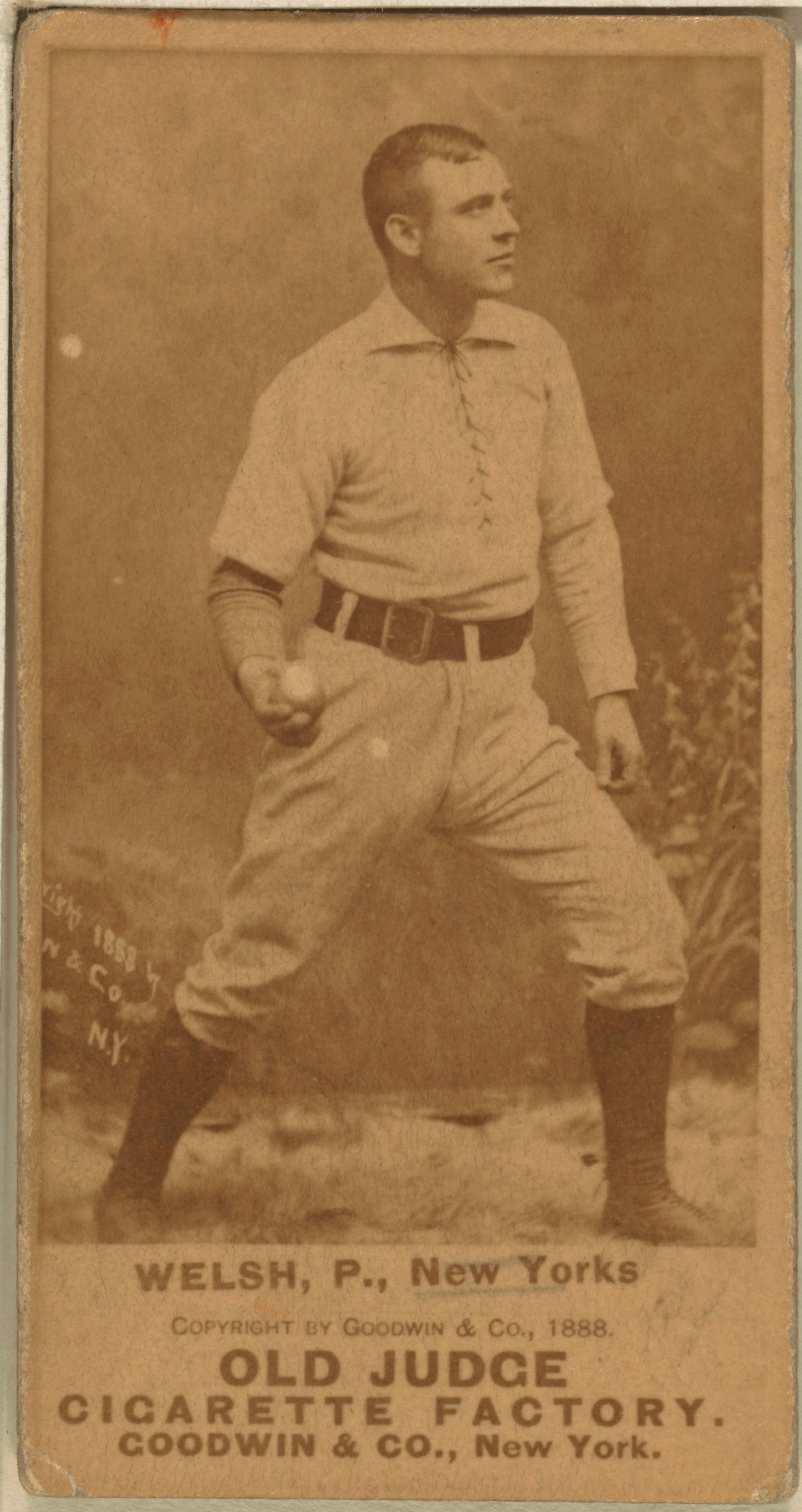

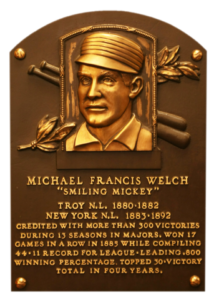

It was surprising that Mickey Welch had such a successful pitching career: He didn’t have much size (the Society for American Baseball Research describes him as “generously listed” at 5-feet-8 and 160 pounds); his fastball was nothing special; and he also had control issues (at times leading the National League in walks surrendered).

However, he spent a lot of time studying each hitter’s strengths and weaknesses. And he had a diverse pitching palette, consisting of various changeups, curveballs, and a rather notorious type of pitch known as a “fadeaway” or “screwball.” This last pitch – which breaks on the batter in the opposite direction of a curveball – has generated debate among historians of the game (adding to the complexity is that some baseball experts consider the fadeaway a distinctly separate pitch from the screwball).

Though Welch is the earliest player credited with using the pitch, “Nobody knows who threw the first screwball,” according to The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches.

Screwballs aside, Mickey Welch was born Michael Francis Walsh in Brooklyn on the Fourth of July, 1859. His father, John Joseph Walsh, was born in 1826 in Toomevara, County Tipperary, according to findagrave.com. This website, though, does not provide a specific county of origin for his mother, Bridget Walsh née Guinan, who was born in Ireland in 1824. But the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) says that she, too, was born in Tipperary.

As to why his playing name (Welch) was different from his birth name (Walsh), some believed that the discrepancy began due to a misspelling in a box score that went uncorrected. Another scenario given was that, because “Walsh” was a somewhat more common surname, he sought to distinguish himself from other local residents who had the same first and last names that he did. A separate account claimed that his parents unofficially changed their family name when he was a child.

Whatever the reason for his modified surname, the future pitching star spent much of his youth on neighborhood sandlots in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. At age 18, he became a professional ball player, earning $45 per month as a pitcher for an unaffiliated team in Poughkeepsie, New York, according to Rich Westcott’s Winningest Pitchers: Baseball’s 300-game Winners.

Welch briefly played in Auburn, New York, before joining a club in Holyoke, Massachusetts. Upon proving himself in Holyoke, he received a call-up to the major league Troy Trojans (of Troy, New York). The right-handed pitcher made his big-league debut on May 1, 1880. It was a disaster, which saw him lose 13 to 1.

But he recovered from this woeful start to pitch an astounding 574 innings during a rookie season that saw him record 34 wins and an ERA of 2.54. He suffered a bit of a sophomore slump, however, in his second season. And in his third season, he under-performed, along with most of his team. In fact, the Troy Trojans struggled so much that they disbanded at the season’s end; the franchise then relocated to Manhattan and was reborn as the New York Gothams (this team soon changed its name to the New York Giants).

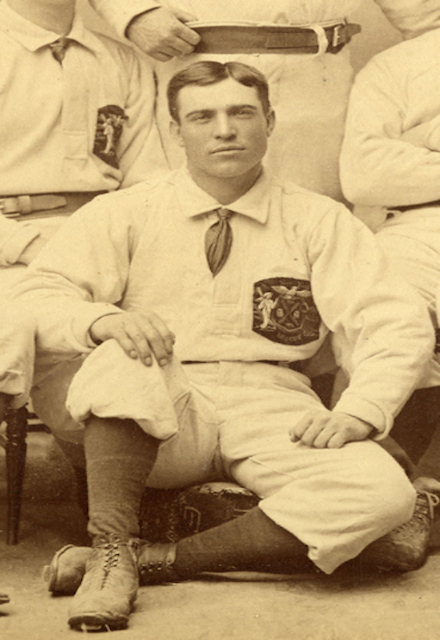

In 1885, Welch had his best season, recording 44 wins with only 11 losses and an ERA of 1.66. That year saw his team add another star pitcher (and Irish-American), Tim Keefe. Welch and Keefe would form baseball’s best pitching duo of the 1880s. They also became good friends, despite having very different temperaments: Keefe was reserved to the point of aloofness, while Welch was everybody’s friend.

Due to his cheerful personality, Welch earned the nickname “Smiling Mickey.” Even the umpires liked him, as he never showed any objections to their calls. The epicenter of many social gatherings, Welch claimed to eschew hard liquor but enjoyed beer so much that he would express his sentiments through poetry. Among his beer-inspired verses: “Pure elixir of malt and hops, Beats all the drugs and all the drops.” He would also compose and recite poetry that advertised bars and restaurants owned by friends, as related in David L. Fleitz’s More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown.

In the late-1880s, Welch was battling arm and back ailments and could no longer pitch so many innings. Still, he managed to play solidly during the 1888 and 1889 seasons. Welch’s contribution, along with that of Tim Keefe and the towering Irish-American slugger Roger Connor, helped the New York Giants win back-to-back championships.

By the start of the 1891 season, Welch – then approaching age 32 – was worn out. The former workhorse pitched only 22 games, compiling a losing record of 5-9 with an ERA of 4.28. In 1892, he pitched only one major league game before being sent down to the minor leagues. After completing his season in the minors, he retired.

Welch’s major league totals include an ERA of 2.71 and a won-loss record of 307-210. Nine separate times, he won 20-plus games in the same season. Pitching a total of more than 4,800 innings in his 13-year career, he completed 525 of the 549 games he started.

In his post-baseball days, Welch attempted several different businesses, such as a hotel saloon, a cigar shop, and a dairy production facility. For some time, he also worked as a steward of the Holyoke Elks Lodge. Much of his free time was spent trading stories with another ex-major league player, “Dirty” Jack Doyle, a County Kerry native who was also a Holyoke resident.

Welch also helped raise a family with his wife, Mary Welch née Whelihan, to whom he was married for more than half a century until her death in 1935. Together they had nine children, seven of whom survived infancy.

Additionally, Welch attended many ball games in Boston and New York, often with his ex-teammate and friend, Tim Keefe. He still felt so attached to the game that he eventually worked as a night watchman at the Polo Grounds in Manhattan.

At Yankee Stadium, which opened in the Bronx in 1923, he served as a gatekeeper and press box attendant. People often gathered around him to hear stories about the different events and personalities from his playing days. Sometimes, Welch would also try to convince listeners that the players of his era were better than Lou Gehrig, Honus Wagner, and Babe Ruth.

By 1938, Welch was the final living member of the original New York Gothams team. In 1941, while residing at the New Hampshire home of a grandson, his condition began to deteriorate. He was transported to the New Hampshire State Hospital in Concord, where he died of congestive heart failure on July 30, 1941, at age 82. He rests in his family’s plot at Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York.

In 1973, Welch received induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame. More than eight decades had passed since his final pitch. The game had changed much during that time, and it was due to change even more. Nowadays, pitchers with seven-figure salaries receive standing ovations for six innings of work, and then spend the rest of the week spitting sunflower seeds in the dugout…After Welch’s 44-win season in 1885, he was at the peak of his career and slated for a new contract. He signed one, which amounted to about $3,000. ♦

Ray Cavanaugh is a freelance scribe from Massachusetts. His mother is from Kerry and his father is a few generations removed from Wexford. He writes Irish America’s “Window on the Past” feature.

Leave a Reply