By Noel Shine

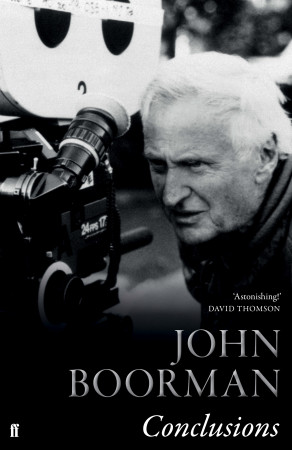

John Boorman is best known as the film director behind the critically acclaimed Deliverance (1972) and Hope and Glory (1987), for which he received Oscar, Golden Globe and BAFTA nominations. His Hollywood breakthrough came with Point Blank (1967), starring Lee Marvin and Angie Dickinson. It was the first of two collaborations with Marvin that he completed, before relocating to Annamoe, County Wicklow, in 1969.

Born in England in 1933, Boorman first used Ireland as a film location with Zardoz (1973) and again with the Oscar nominated, Excalibur (1981). He went on to serve as the first Chairman of the Irish Film Board and has featured a wide array of Irish talent in front of camera as well as behind, throughout his career. His last cinematic outing, Queen and Country (2014) featured our own Sinead Cusack, Brian F. O’Byrne, and Pat Shortt.

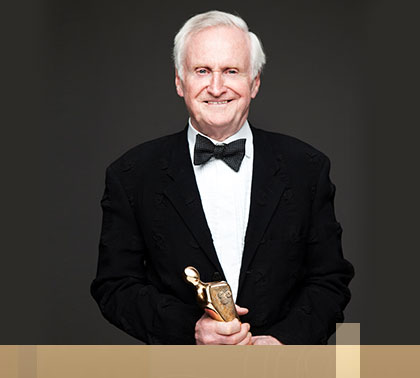

Presented with an IFTA (Irish Film & Television) Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010, he said:

“This award is a tribute to all the Irish actors and crews who have made my films for me.”

https://ifta.ie/life_time/john_boorman.php

At 87 years now, Boorman continues to enjoy his retirement. I caught up with him, as he was ‘cocooning’ at Annamoe, Co. Wicklow to discuss his new autobiography, Conclusions, his life in film, Covid-19, and much more besides.

How is ‘cocooning’ during ‘lockdown’ agreeing with you? Or are you cracking up?

Well, I’m isolating with my son, Lee and my daughter, Lily-Mae.

Many media commentators have likened this period of global pandemic to the experience of life during the war. You lived through ‘the Blitz’, do you see any merit in that comparison?

I was seven when the war started. It was rather like this time, insofar as you had to learn to rely on your own resources. During the war, you grew your vegetables, because you knew you weren’t going to get them otherwise. Food was rationed right up until 1947 and you had coupons for clothes also. Everybody just got on with it. But this thing (Covid-19) has been a terrible disaster for thousands of people, and so many have died from it. If any good can come from this, is the realization of how much we have been polluting the atmosphere with so many planes flying every day. Suddenly, we have got this clean planet with clear rivers and blue skies. I hope that lessons are learnt from that.

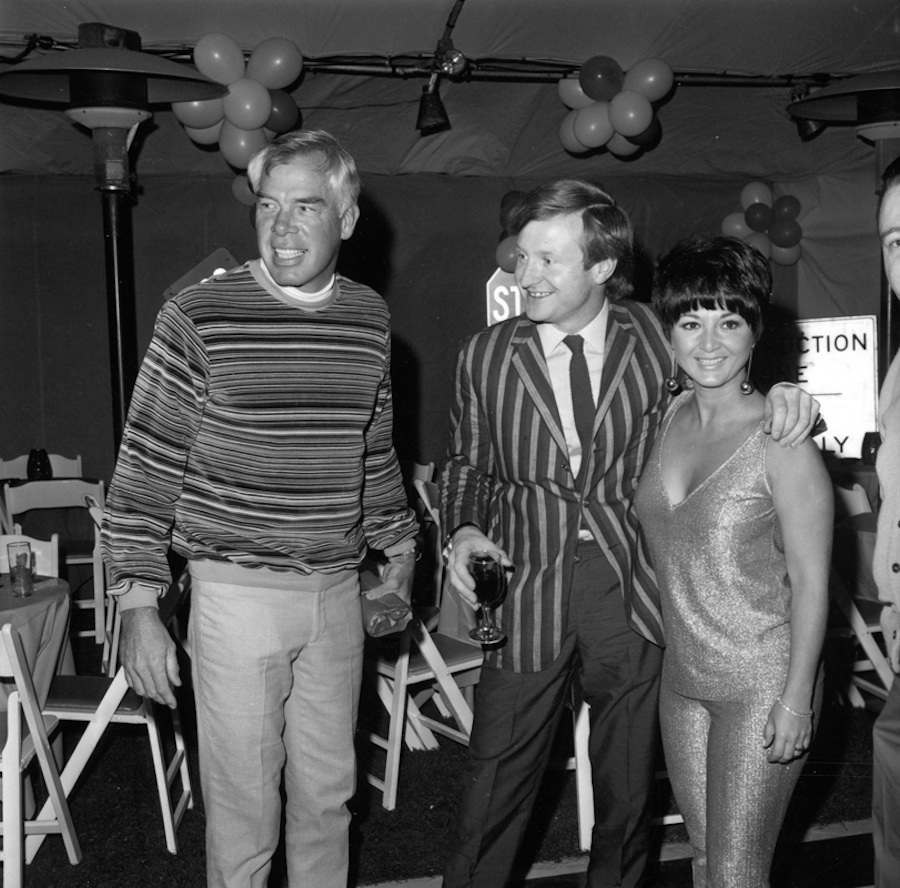

Your Hollywood breakthrough, Point Blank in 1967, was a dream scenario for a budding director insofar as you had Lee Marvin cast in the lead role, and full control over the movie.

Lee had just won the academy award for Cat Ballou (1965) and the studio heads at MGM approved everything he wanted to do with Point Blank, and he, in turn, deferred all of his approvals to me. I was this young, English director with carte blanche to do as I pleased. When I put it together, I had to show it to these studio executives, including Margaret Booth, who was in charge of editing at MGM, going back to Gone With The Wind (1939). Anyway, at the end of the screening they started talking about doing reshoots, they didn’t understand it at all really. She spoke up from the back of the room, “You cut one frame out of this picture over my dead body!” I had a lot of support. I was fortunate.

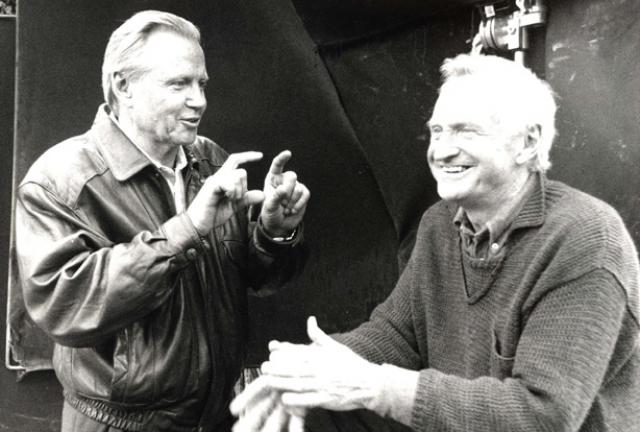

You remained lifelong friends with Lee Marvin, until his death in 1987. How do you reflect on him now? I think Lee Marvin was an extraordinary man, because not only did he agree to make Point Blank with me, even though I was unknown, but he liked what I wanted to do, and he recognized how difficult it was going to be to make that kind of film in Hollywood, if I didn’t have control. So, he engineered it, so that I did.

He supported me all the way through the picture. For instance, there was a scene I had to shoot in Alcatraz, I just couldn’t get the scene together. Lee came over to me and said, “Are you in trouble?” and I said, “ I can’t get this right!” So, he went off and pretended to be drunk – to deflect attention away from me.

He started roaring and singing, and the production manager came over to me and said, “You see what state Lee is in? There’s no way you can shoot a picture when he is like this!” [laughs] It gave me a few minutes to get my act together. Poor Lee, he was great [sighs]he became a great friend. I made a documentary film about him.

There are some great photos from the wrap party for Point Blank on the internet. They include you with Lee, Charles Bronson, Steve McQueen, and Burt Reynolds. You cast Reynolds five years later in Deliverance. Had you always had it mind to cast him in a film?

Those guys were pals of Lee that he had invited. I didn’t know Burt at all. The studios would insist on cutting the budget all the time, to minimize their risk to Deliverance. They said to me, “OK, we’ll do it if you can get two megastars”, and I got Jack Nicholson and Marlon Brando. I came back to them and they said that Marlon Brando was box office poison and [that] I was paying Jack Nicholson too much. So, they said, “Go and make it very cheap with unknowns” Burt came to me off the back of three cancelled TV shows. He was right at rock bottom. They said to me [laughs] if you’d been living in this country [the US] you would never have cast Burt Reynolds! I didn’t know about his failures, but I believed that Burt would be right for this character. We made the whole picture for about $2 million and it grossed over $100 million.

Cary Grant was a neighbor of yours?

In Malibu, yes. He was estranged from Dyan Cannon, but they had a baby, Jennifer, and a nanny used to prop her up in the seat next to Grant. He would drive, very slowly, up and down a little private road there in his Rolls-Royce [laughs]. He came from Bristol, where I had worked for the BBC, but I could never pluck up the courage to say, ‘Mr Archie Leach, don’t you miss the Clifton Suspension Bridge?’

You found life in Los Angeles dispiriting. In what respect?

Well, it’s a good place to make a film alright, because all the facilities are on hand – they have got great technicians there. But LA is a shapeless place; it doesn’t have any center to pull it together. As you start living there, you find yourself falling apart, you can’t hold together your identity. At least, that’s how I felt. After I made Hell In The Pacific (1968) with Lee, I went to London and didn’t go back. Even, while making Deliverance, I never went near Los Angeles; it was made entirely on location in Georgia. I could have stayed and had a Los Angeles director’s career, but I preferred to try and make independent films and go my own way.

I read that you met Elvis at MGM, and that he tentatively discussed working with you.

He’d seen the Beatles’ films and my film, Catch Us If You Can [featuring the Dave Clark Five] and he wanted to effect better pictures, but he was afraid to upset MGM and the Colonel, his manager. He was embarrassed about being ‘Elvis Presley.’ When you talked to him, he was shy and deferential, and he didn’t ever really take his own identity into his own hands, but what a performer!

Are you proud of the fact that your films helped establish the careers of a whole host of actors, from Burt Reynolds in Deliverance (1972) to Daniel Radcliffe, in The Tailor of Panama (2001)?

Yes [laughs], and Gabriel Byrne and Liam Neeson, who both featured in Excalibur. One of the jobs of a director is to look for talent, recognize it and try to encourage it. There’s two kinds of acting; there’s ‘survival’ acting, where the actor looks at a scene and thinks – I know I can get through this scene without making a fool of myself. Then there’s the sort of actor who has great trust in you, as a director, and is willing to take chances and metaphorically, ‘jump off a cliff’ for you, like Jon Voight or Brendan Gleeson. It’s a matter of trust, really.

When you arrived in Hollywood in 1966, you met people whose careers extended back to the days of DW Griffiths and Mack Sennet. Combined with your own experience in the industry, that represents over a century of cinema history. Do you think the great era of cinema and film making has passed with the rise of Netflix and ‘binge’ viewing of box sets?

I think what’s happening now, particularly with high-end TV series, from HBO – Game of Thrones, Mad Men and so on; they are all shot with multiple cameras against green screen. So, nobody goes out now with a whole crew and waits for the sun to come out. They shoot all those scenes in the countryside, put the actors in front of the blue screen, and match them together. Now that people know the computer can manipulate everything, they are no longer as impressed. The ideas are very commercial now. Every year one or two worthy films get made – Roma was the best film made last year – but, it has become progressively difficult for people to make anything original.

In your book Conclusions, you expounded on the fact that it is as difficult as ever to raise finance for film projects.

When I went back to Los Angeles to work on the post-production of Point Blank, the hotel that I stayed in had just been built. One night, I read a brochure about it in my room, and it turned out that it cost as much to build that new hotel, as it did to make Point Blank. That hotel is still there, making money. Films are an ephemeral experience; their worth, to an investor, is not as immediately apparent. In the first book that I wrote, Money Into Light, I hypothesized that really is what is happening in this process; you take all this money, all these actors and scenes and, what you have, at the end of the day, is a light flickering on a wall. It’s a hard sell.

Maureen O’Hara used to say that investing in movies was second only to blowing your money at the racetrack.

Yes, I once asked Paul Rassam, the French film producer, had anyone ever worked out what percentage of new movies actually make money, and he said to me, “In human births, 94 percent are healthy, 5 percent have some minor defect, 1 percent die. With movies, it’s the other way round.

John, I would have preferred to meet you there at Annamoe, but we live in strange times.

Thank you, I appreciated our little chat

I believe you have planted thousands of trees on your estate, do you still get out and walk among them?

I do yes, as a matter of fact, I’m keeping a nature diary, it’s keeping me out of mischief.

Conclusions is published by Faber and Faber.

John Boorman lived in Annamoe, County Wicklow for almost 50 years, but put his home up for sale in 2022. He now lives in Surrey, England, close to his son, Charlie.

Noel Shine is a freelance photographer/journalist based in Kells, County Meath. He is a regular contributor to American, Canadian and British magazines on Irish music, books and films. A recent graduate in Media and Film Production, his photography portfolio includes 20th century icons, Bob Dylan, James Brown, Bono, Maureen O’Hara and others.

Noel Shine is a freelance photographer/journalist based in Kells, County Meath. He is a regular contributor to American, Canadian and British magazines on Irish music, books and films. A recent graduate in Media and Film Production, his photography portfolio includes 20th century icons, Bob Dylan, James Brown, Bono, Maureen O’Hara and others.

Wonderful!

Brilliant interview