He deserves a better judgment

As Bobby Kennedy lay dying on a hotel kitchen floor, we’re told his last words were of concern for those around him who had also been shot. “Is everybody okay?” Kennedy asked.

These noble, altruistic last conscious thoughts chime with how many people see him – a champion of the poor, “a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it,” as his brother Ted said at his funeral.

In fact, according to an ambulance man attending to the senator, his actual last words were “Don’t lift me, don’t lift me,” an understandable and natural reaction from a gun victim in tremendous pain.

The “Don’t lift me” last words turn out to be no less poignant or meaningful than his worry for others. Since his death, Kennedy’s political reputation has been elevated unhelpfully, and he has yet to be subjected to the candid historical scrutiny he deserves.

He has been over-romanticized and idealized. Just before Bill Clinton’s presidential nomination at the 1992 Democratic convention, a documentary film about Kennedy was shown to delegates in the hall. For 20 minutes the convention stood silent as Kennedy’s words echoed across the decades to a new generation of Democrats desperate for victory after long years of conservatism. The symbolism was clear – Kennedy had been the soul of liberal America, and lost in the swirl of tragedy and romance and the What Might Have Been is a clear analysis of what he really contributed to American history.

For many American (and non-American) progressives, he was the last great radical, the last liberal icon. “Bobby Kennedy was one of my heroes,” said President Obama. “He was someone who showed us the power of acting on our ideals, the idea that any of us can be one of the ‘million different centers of energy and daring’ that ultimately combine to change the world for the better.”

Was Kennedy really as great as the mythology suggests? Honestly I don’t think we know yet.

There have been many biographies written about him since his death.  I wrote one myself, but all have failed to really locate an appropriate place for him in the pantheon of American political history.

I wrote one myself, but all have failed to really locate an appropriate place for him in the pantheon of American political history.

Ten years after Kennedy’s death, Arthur Schlesinger’s terrific book on Kennedy, Robert Kennedy and His Times, appeared. It had a great influence on me as a 15 year-old in London. I can’t really explain or understand why, but after I got it for Christmas (paperback edition, obviously) I was hooked – I studied his meteoric political career as attorney general when his brother was President, his four years as New York senator, and a three-month electrifying, romantic, presidential campaign that ended on the kitchen floor in a Los Angeles hotel.

Schlesinger’s book is magnificent, the best written about Kennedy so far, but the author was Kennedy’s longtime friend. It was written only a few years after his death, with the U.S. still raw from the Vietnam War that Kennedy tried to stop. Schlesinger was close, too close, to his subject.

Schlesinger’s book is magnificent, the best written about Kennedy so far, but the author was Kennedy’s longtime friend. It was written only a few years after his death, with the U.S. still raw from the Vietnam War that Kennedy tried to stop. Schlesinger was close, too close, to his subject.

The other biographies often veer towards hagiographies, with authors finding it hard not to judge Kennedy’s career unemotionally. My biography of Kennedy came out 25 years after he’d been killed, but I also failed to be objective or detached enough.

Don’t get me wrong. I think Kennedy was a fascinating, extraordinary politician who could have entirely changed American history. I’m not looking for anyone to tear down his reputation.

I think he was reinventing politics, and wonder how different the world would be if he had become president in 1968 – there would have been no Watergate, and a quicker end to the Vietnam War. He understood white racism and black anger in a way few white politicians ever have. Who knows what he might have done from the White House during those awful early years of the Northern Ireland Troubles. I’m a Bobby Kennedy fan, and that’s the problem. Fans don’t make the best historians.

Some genuinely gifted writers have tried. Larry Tye’s 2017 Bobby Kennedy: The Making of Liberal Icon is beautifully written, but Kennedy deserves a fresh judgment, a clearer-eyed assessment from a new generation of historians. It’s time to reassess whether the role he played in ending the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis was as pivotal as most of us wrote, or whether he really did have the makings of a new coalition of white and black working class voters that could have been – and could be – a new base for the Democrats, and whether Kennedy’s mid-1960s politics has anything to say to us half a century later.

Some genuinely gifted writers have tried. Larry Tye’s 2017 Bobby Kennedy: The Making of Liberal Icon is beautifully written, but Kennedy deserves a fresh judgment, a clearer-eyed assessment from a new generation of historians. It’s time to reassess whether the role he played in ending the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis was as pivotal as most of us wrote, or whether he really did have the makings of a new coalition of white and black working class voters that could have been – and could be – a new base for the Democrats, and whether Kennedy’s mid-1960s politics has anything to say to us half a century later.

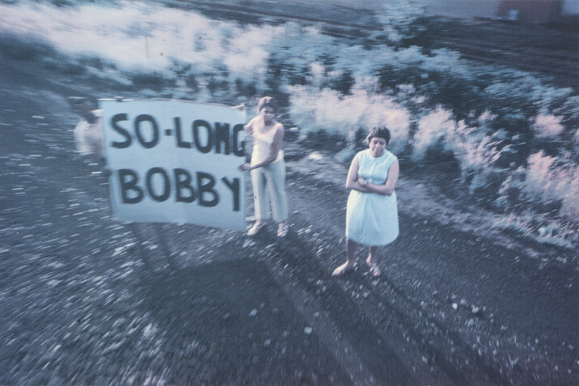

His last wish, ‘don’t lift me,” hasn’t really been respected as we’ve too often raised him up as an impossibly perfect hero. He deserves a better judgment. Maybe young historians can take that on. ♦

Photo: The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art 2019 exhibit “The Train: RFK’s Last Journey.”

Read A Touch of Irish from Irish America’s June/July 2018 issue.

Brian Dooley is a Senior Advisor for Human Rights First as well as author of Choosing the Green: Second Generation Irish and the Cause of Ireland.

Brian Dooley is a Senior Advisor for Human Rights First as well as author of Choosing the Green: Second Generation Irish and the Cause of Ireland.

Follow Brian on Twitter @dooley_dooley.

Leave a Reply