By Christine Kinealy

Paul Robeson was born in in Princeton in New Jersey in 1898. His father was a former runaway slave who had become a Presbyterian minister and his mother was part of a Quaker abolitionist family. His mother, Anna Louisa Bustill, died in a fire when Robeson was aged 6.

Despite growing up in an era of segregation, Robeson proved to be gifted in both in sports and academic studies. At 17, he was awarded a scholarship to Rutgers University, where he excelled in American Football and as a student, becoming his class valedictorian. After graduating, he attended Columbia University Law School. While there, Robeson met and married Eslanda Cordoza Goode, who became the first black woman to head a pathology laboratory. In the early 1920s, Robeson took a job with a New York law firm, but he left when a white secretary refused to take diction from him.

The talented Robeson decided he would use his use his acting skills to work in the theatre, where he could champion African-American history and culture. His move coincided with the Harlem Renaissance that, similar to the Gaelic Revival in Ireland, sought to revive a pride in, and knowledge of, the rich traditions and heritage of his people. The Harlem Renaissance fostered a golden age in African-American culture, which was manifested in literature, music, stage performance and art.

While performing in amateur theatricals, Robeson caught the attention of an Irish-American writer, Eugene O’Neill. O’Neill was descended from Irish immigrants, his father’s family having left Ireland during the Great Famine. When he met Robeson, he had already won two Pulitzer prizes for Drama, while his play, The Emperor Jones, had opened in 1920 to great acclaim. O’Neill persuaded Robeson to act in the premiere of his now largely forgotten play, All God’s Chillun Got Wings. It was a controversial and brave choice. In the play, Robeson portrayed the black husband of an abusive white woman, who increasingly resented her husband’s skin color, leading her to destroy his promising career as a lawyer. On-stage, his character kissed the hand of his wife, which caused a national uproar. Nonetheless, a new stage star was born and a new partnership had been created between an Irish American writer and an African American writer, whose talents, it seemed, had no limits.

The following year, Robeson relocated to London, to take play lead in O’Neill’s stage-hit, The Emperor Jones, to positive reviews. But it was his appearance in the West End premiere of Showboat in 1928, and his plaintive rendition of Ol’ Man River, that propelled Robeson into international recognition. Shortly afterwards, he played Othello—thus becoming the first black man to do so. Less than four years after giving up the law due to racism, Robeson had become one of the most-sought-after singers and actors in the world.

More success followed as Hollywood beckoned, with Robeson starring in a number of well-received movies—some of them are now regarded as trite for the stereotyping of people of African origin. At the time, however, they were commercially and critically successful. Throughout his meteoric rise, Robeson remaining committed to learning more about African culture, studying Swahili and Linguistics, enrolling at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London in 1934. He also remained active in progressive politics, expressing his support for oppressed people everywhere, including miners in Wales and Scotland.

At the height of his fame in the 1930s, Robeson visited Ireland on at least three occasions to perform his trade-mark negro spirituals and increasing repertoire of national folk songs. He first travelled to Dublin in 1930, when Irish newspapers announced that “a famous negro singer to visit Dublin.” It was a brief visit. During his second visit in 1935, coverage was more extensive with the Irish Press announcing, “The giant 36-year old singer of negro spirituals, Paul Robeson, who has been successively a Methodist preacher, All-America rugger star, lawyer, character actor and leading man on the films, arrived in Dublin last evening.”

During this longer visit, Robeson gave several lengthy interviews in which he explained both his special relationship with Eugene O’Neill and his love for Ireland’s culture. He particularly admired Irish literature and music and, in regard to the former, stated that he was an avid reader of W.B Yeats. Known for singing Russian and Finnish folk in their native languages, he told one reporter that, “Irish folk songs are the best:”

I know some Irish folk songs, but as I do not know the language, I feel that I am not able to sing them properly. I seriously say that Ireland has the finest folk music in the world. Without a knowledge of the language I find Irish folk songs too difficult to sing in public, but I often sing them in private. ‘The Castle of Dromore’ is a special favourite of mine.

He also spoke of his friendship with Irish Abbey actors, Sarah Allgood, Joe Kerrigan and the late Sidney Morgan, describing the lilt of their speech as being “the loveliest imaginable,” attributing it to the “musical quality that their English has derived from their Gaelic background.” Morgan had played alongside Robeson in Emperor Jones and during the interludes he had sung Irish melodies to his fellow actors. During the interview Robeson also spoke of racism in America and said that although there were traces of it in Europe, it was not as pronounced. He added that, “I have never let such things interfere with my career as an artist.” Robeson admitted he had experienced prejudice in London, but that it was less evident in Ireland.

Audiences in Dublin, Cork, Limerick, and Belfast were charmed by Robeson’s live performances. It appeared that his personality shone through, one musical critic reporting:

One of Robeson’s attractions is his merry sense of humour, and the curious thing is that, while his moulding of phrases in serious songs is not always faultless, be carries on the verbal and musical phrasing with telling effect. Robeson never exaggerates either his expression or his tone. It flows naturally and with ease.

Others referred to his “sincerity and an engaging simplicity of manner” and his “impressive personality.” A more intimate insight was provided by a journalist with the Evening Herald, who found himself alone with Robeson in the Shelbourne Hotel after all other visitors had left. They spent a few hours together which, for the journalist, was particularly memorable:

I have interviewed many celebrities on behalf of my paper before, but I never enjoyed anything so much as my talk with this negro gentleman. It was not so much an interview, as a talk between friends.

Robeson again spoke of his love for traditional Irish songs and his friendship with several of the Abbey players. Like Frederick Douglass almost 100 years earlier, Robeson made comparisons between the music of Ireland and those sung on the plantations, saying of Irish songs, “they are the saddest songs in the world and those strange plaintive airs have so much in common with the songs of my people.” To prove his point, Robeson then played the piano and intermingled both types of songs:

And the little room was flooded with a strange; out-of-the-period melody which I still recognized as having, an Irish motif. Then, it changed and while there was still resemblance of the Irish music it had taken on a more vigorous and somewhat harsher note.

This private concert, in a small hotel room in Dublin, that fused the music of two peoples who had each suffered centuries of oppression and negative stereotyping, was sadly never repeated in public.

Robeson toured Ireland again in 1939. Shortly afterwards, as Europe hurtled towards war, he and his wife returned to America. At this stage, Robeson had become an outspoken critic of fascism, visiting Spain during their Civil War, where he sang to wounded Republican soldiers. He also spoke out on behalf of Indian independence and of the right of African nations to independence. In 1946, following the lynching of four African Americans, Robeson called on Congress to enact civil rights legislation. However, Robeson’s political activism, and his admiration for the Soviet Union, brought him to the attention of the F.B.I. and the Un-American Activities Committee. In 1950, his passport was revoked, meaning he could no longer travel overseas to perform. Effectively, his career was stifled. Although his passport was returned after eight years, his health and spirit were broken. Suffering from depression, Robeson retired to Philadelphia in self-imposed seclusion and died there in 1976.

Born the son of a former slave, in an age of open segregation and persecution, Robeson was one of the most multi-talented and humanitarian artists of the early twentieth century. Yet, his unbounded compassion for the oppressed and his indefatigable championing of human rights also meant that he became one of the most ostracized and vilified.

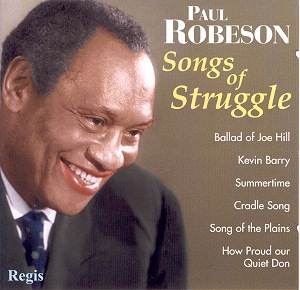

Robeson’s visits to Ireland coincided with his international political awakening. He explained, “The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative”. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Robeson did record one Irish song, which appeared on the compilation album, “Songs of Struggle.” The song was “Kevin Barry,” a lament for a member of the Irish Republic Army, who was hanged in 1920. He was 18 years old and a medical student:

In Mountjoy jail one Monday morning

High upon the gallows tree,

Kevin Barry gave his young life

For the cause of liberty.

Christine Kinealy is the Director of the Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac College and a member of the Irish America Hall of Fame. Christine is a regular contributor to Irish America Magazine.

I love this article! Thank you

I did not know much about Paul Roberson but your article changed that. What a talented man. He seem to have have a fondness for Ireland and their people and their music!

My father was from Trinidad and he attended medical school at the University College of Dublin. I have a photo of Mr. Robeson, his wife, and accompanist visiting the West Indian and African medical students. I have a group photo which I would be delighted to share. I donated the original to the Robeson Cultural Center at Rutgers but it somehow disappeared. I do have a copy however. Our family has many stories of my father’s time in Ireland and his enduring fondness for Irish whiskey. I do hope to visit sometime. My father became a renowned Ear, Nose and Throat surgeon in New York, and while in Dublin, won the John S. McCardle medal for surgery in 1936. Your article has helped narrow down the date of the photo. The photo was probably taken during the 1935 visit. 1939 was probably too late.

Hi Karen,

I’m researching a student from Jamaica in Dublin in 30s who might have known your father/been in that picture, I’d love to get in touch – Karl O’Hanlon (Maynooth University, Ireland – you can find my email address online)

Thanks for sharing this wonderful material on one of the most brilliant and gifted artists of the 20th Century, Bar none! We have been fans of

Mr.Robeson’s for more than six decades via our physician father who was a friend and colleague of Karen’s father, Dr. Errol Thompson.So glad that you could share the wonderful archival picture Of your Father and the

Robeson’s and the African and Caribbean medical students in Dublin Ireland medical school in the 1930s. The Irish are famous freedom fighters and the self less Irish eighteen year old Kevin Barry was no exception. The song and tribute are very moving and captures the emotional power of Mr. Robeson for eternity. Thanks so much Karen for sharing. I’ve passed the wonderful article on to others who also appreciate your thoughtfulness!

Robeson was an inciter and anti-America.Nothing about him to be admired.

Yes your point is well taken. My questions are is it possible for an individual, based on actual experience have an 180 degree different view of America? Often ones BELIEF in “The Shinning City on A Hill” overlook an opposite Point of View held by the others. Does having a different Point of View mean your are no longer an American? Often the “Other American” (based on personal experience) tend to agree with the majority of the world population on “The Real America” e.g. anti-Humanity, Anti- Democracy, Anti – justice, Anti-freedom, pro-materialism, pro-Totalitarianism, pro-authoritarianism.