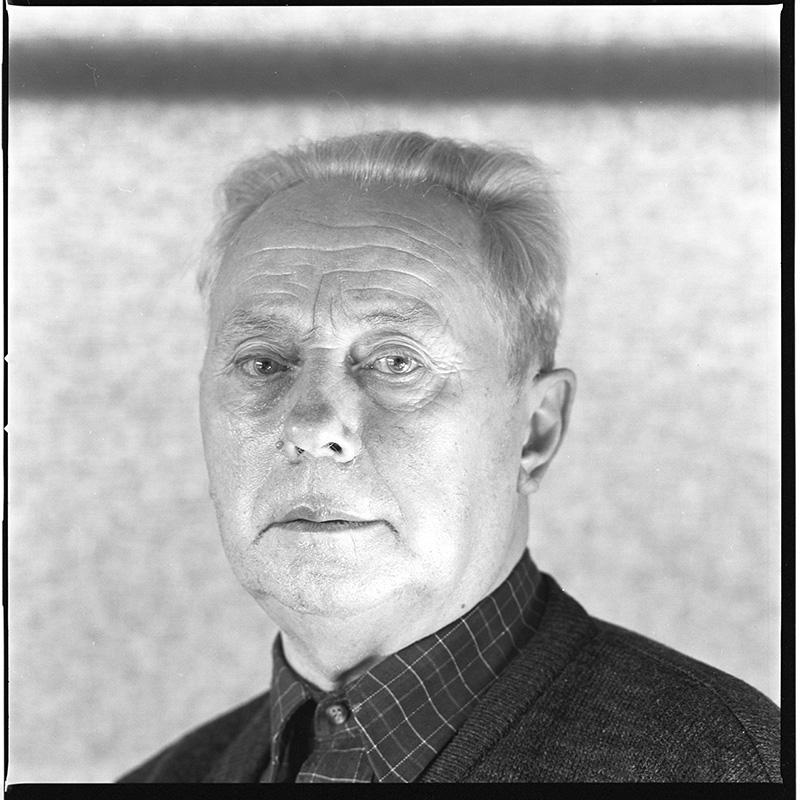

The man behind the Provisional IRA was Londoner Seán MacStiofáin.

By Brian Dooley

If all politics really is local, as Tip O’Neill suggested, then it’s hard to know where to place Seán MacStiofáin, founder of the Provisional IRA.

MacStiofáin was born and grew up in London as John Stephenson. His father was English and his mother Irish, from Belfast. He didn’t visit Ireland until he was 22, in 1950. By then he’d already been in the IRA for a year.

Strange, but not extraordinary, as he was quick to point out to me, citing the examples of many English and Scottish-born Republican Volunteers whose first trip to Ireland was to take part in the 1916 Easter Rising.

I spent many hours interviewing MacStiofáin in 2000, the year before he died. He’s a largely forgotten character these days, sidelined in the history of modern Irish Republicanism, despite his enormous importance in the early 1970s.

MacStiofáin spent six years in English jails during the 1950s after being caught in Essex stealing weapons for the IRA, and on his release in 1959 moved to Ireland. Although officially part of the Cork IRA he was always an outsider, retaining a strong Cockney accent throughout his life.

He told me how, as a teenager, he had immersed himself in Republican history, identifying closely with the English-born IRA. “[In 1916] a band of Volunteers came to Ireland from London, Liverpool and Glasgow to take part in the Rising… it was the first time many of them had been to Ireland…I’m not an exception,” he said.

When the IRA split at the end of the 1960s over the crisis of how it should react to the emerging violence in the north, he became leader of one of the two factions. One wing favoured alignment with the leftist international revolutionary movement, while the another – backed by MacStiofáin – emphasised the need to protect Catholic neighbourhoods in Belfast and elsewhere with guns.

He led the split from the Official IRA and founded the Provisionals, becoming its first Chief of Staff in 1970. His outsider status was an advantage in the bitter split, as he wasn’t seen to be pushing a local neighbourhood agenda – the rift wasn’t about the Belfast IRA versus the Derry IRA, or city Republicans against their country colleagues.

MacStiofáin headed the Provisional IRA for its first three years, during the bloodiest times of The Troubles. He encouraged the use of car bombs, and gave the final order for the Bloody Friday attacks of July 1972, when around 20 bombs went off in Belfast in just over an hour, killing nine people, including five civilians. That year MacStiofáin’s IRA carried out an estimated 13,000 bombings.

That year also saw Bloody Sunday, when the British Army killed 13 unarmed protestors in Derry, and in 1972 MacStiofáin led the IRA in talks with the British government in London in a brief and unsuccessful negotiation.

He oversaw an aggressive, violent campaign aimed at quickly driving the British Army out of the north of Ireland, understanding the conflict as a largely orthodox war of liberation where Britain would eventually withdraw as it had from the rest of its former Empire.

He told me he used his English accent to slip through British military checkpoints, and that he emulated German Filed Marshall Rommel’s approach of “going to the front lines” and spending as much time as he could with local IRA Volunteers who were doing the fighting.

When he was arrested at the end of 1972 in the south of Ireland, he immediately embarked on a thirst and hunger strike before agreeing to eat again after eight weeks. His power in the IRA quickly evaporated while he was in jail.

A few months later he was released, but his demise in the IRA was swift, with senior Republicans maneuvering him out of power. “He had served his purpose,” said one.

MacStiofáin told me he had opposed the bombing of English cities on tactical grounds, and vetoed such plans when they were presented to him as head of the IRA. Within months of him being eased out of the leadership, the IRA leadership ordered the bombing of London in early 1973.

He faded from the Republican scene, dedicating the rest of his life to promoting the Irish language, which he’d originally learned in prison in England.

The full story behind his fall within the movement is unclear, but the rootlessness which enabled his rise might have also led to his swift downfall. There was no constituency in west Belfast or the Bogside or rural Tyrone to fight his corner, no neighbourhood historical society to keep his memory alive, no plaque on the wall honoring his birthplace. He wasn’t anyone’s local hero, and had no geographical power base.

He’s rarely included in the pantheon of IRA legends, although Republican heavyweights Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness attended his funeral.

But sadly for Londoner MacStiofáin, he’s been largely left out of recent Republican mythology, because in the end all politics is local.

Brian Dooley is author of Choosing the Green: Second Generation Irish and the Cause of Ireland, now available free online at London Metropolitan University Archives http://repository.londonmet.ac.uk/5438/1/AIB.BD.Z.1.2004_Text.pdf

Follow Brian on Twitter @dooley_dooley.

Thanks for publishing important history–not to be forgotten.

I remember, much of the history of Irish republicanism is hidden in England an Scotland, Your have to start with the fenians not much in Wales , but odd places spring up like the Isle of Wight Thomas Clarke even Gosport

I read a number of years ago in The Irish Post (newspaper of the Irish in Britain) that someone was writing a biography of MacStiofàin, but I don’t think they succeeded.