Over the last four decades, stamp-collecting, also known as “philately,” has been undergoing a slow but sure death. This has been mirrored by a decline in letter-writing and a similar wane in the use of cursive writing. Consequently, the hobby of stamp-collecting, so beloved by generations of schoolchildren, is mostly the preserve of people above the age of 60. Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University has recently been gifted two extensive collections of Irish stamps. While their monetary value may have dropped, their value in providing an insight into Irish history and culture remains invaluable. The stamps in these collections date from the formation of the new Free State in the 1920s and they recount the early decades of Irish independence in an unusual way. Postage stamps have been in existence for almost 200 years. The world’s first postage stamps were issued in London in 1840 for use in Britain and in Ireland.

The original stamp was black and cost one penny, but the color was impractical for showing any marks, so, in 1841, “Penny Reds” were introduced. British stamps continued to be used in Ireland until 1922. In the previous year, Ireland had been partitioned and two new states formed – 26 counties to be known as the Irish Free State, the remaining six as Northern Ireland. The latter continued to be part of the United Kingdom and to use British stamps. The new Free State, however, determined to assert its

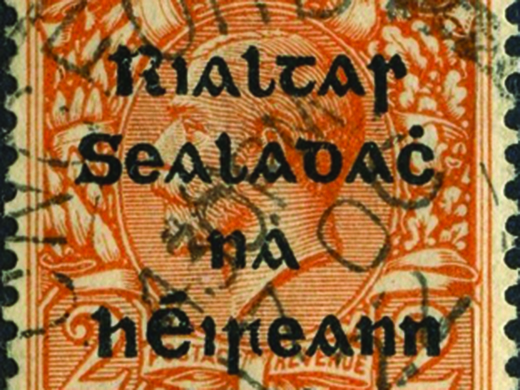

independence in every way, printed over the British stamps with an impress saying “Rialtas Sealadach na hÉireann 1922,” which translated as “Provisional Government of Ireland 1922.” Simultaneously, a competition was held to design the first distinctive stamps of the new country.

On December 6, 1922, the first Irish stamp was issued. It was green and the text was all in Irish, made further distinctive by the use of a “Celtic” font. It depicted a map of Ireland, tellingly, with no partition. The word ÉIRE featured prominently. All was surrounded by traditional Irish artwork:

shamrocks, triskeles, etc. It cost 2d. For such a small object, the stamp made a strong, unmistakable statement about what it meant to be Irish. In the same year, Irish post-boxes were painted green (post-boxes throughout the British Empire had traditionally been red). It was another gesture of Ireland’s newfound independence. In 1929, the first commemorative stamp was issued. It celebrated the 100th anniversary of Catholic emancipation and featured “the Liberator,” Daniel O’Connell. Multiple other commemorative stamps followed, including to honor the bicentenary of the Royal Dublin Society (1931), to mark the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Gaelic Athletic Association in 1934, and multiple stamps celebrating the Easter Rising in 1916 (stamps have been issued to mark its 25th, 50th, and 75th anniversaries). Events outside of Ireland were also observed. Two stamps were issued in 1939 to celebrate America achieving it independence, each showing George Washington, the eagle from the Great Seal, and an Irish harp. Individuals have also featured, including stamps commemorating William Rowan Hamilton (1805-1865), an Irish mathematician renowned for his discovery of quaternions in 1843; the tercentenary of the death of Micheál Ó Cléirigh (c. 1590-1643), an Irish chronicler and chief author of the Annals of the Four Masters; the 150th anniversary of the execution of Robert Emmet, leader of the 1803 republican rising. Women were little in evidence in the early decades of Irish stamps, although the centenary of the death of Mother Mary Aikenhead (1787-1858), founder of the Religious Sisters of Charity, the Sisters of Charity of Australia, and of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Dublin were issued in 1958.

Special events in the history of the state were memorialized, including the opening of the Shannon hydroelectric power station in 1929; the Marian Year in Ireland (1954), the year in which Catholics throughout the world remembered Mary, the mother of Jesus; and the International Year for Human Rights in 1968, which celebrated the 20th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Clearly, the early stamps reflected the values of the newly created Free State, and, after 1949, the Republic. Inevitably, they tended to be Catholic, insular, and male in their outlook. But, like so much in Ireland, stamps have changed and increasingly reflect the country’s diversity. In 2018, two new postage stamps featuring Martin Luther King, Jr. and Nelson Mandela were issued as part of a set called “International Statesmen in 2019,” and two commemorative stamps paid tribute to the Dublin rock band Thin Lizzy and their lead performer, Phil Lynott. In June 2020, stamps highlighting Ireland’s Pride movement will appear. The contribution of women is also being recognized more: in 2019, the centenary of the birth of Irish author, Iris Murdoch was celebrated and, in 2020, Maureen O’Hara will be honored with her own stamp.Overall, Irish stamps provide a visual history of almost 100 years of Irish independence. They offer a unique insight into how the newly created Irish State viewed itself and its place in the world. They are also powerful reminders of how the country has changed over a century. ♦

Where can I get these stamps?