When this year’s postponed St. Patrick’s Day parade is rescheduled, the New York Army National Guard’s 1st Battalion (the Fighting 69th Infantry Regiment), led by two Irish wolfhound mascots, will march up Fifth Avenue and mark its 169th year in the St. Patrick’s Day parade. The tradition began in New York City in 1762; when the first parade honoring the patron saint of Ireland was held by Irish soldiers serving in the British army.

The Fighting 69th in its present form was organized by Irish revolutionary and Civil War Union general Thomas Francis Meagher of County Waterford. The raison d’être for inviting the 69th to lead the St. Patrick’s Day parade in 1851 was to protect the Irish from the violence orchestrated by the anti-immigrant “Know-Nothings.”

In a St. Patrick’s Day speech in 1855, Meagher denounced anti-immigrant movements, insisting that America “does itself great wrong when it supposes, in view of that which occurs in the emigration from Ireland, that it can fail in its strength because of the addition which it receives from poor old Ireland, drawing out drops of her choicest blood, and infusing them into the veins of this young giant, that he may go forward with more rapid strides to achieve the brilliant conquest which awaits him in the future.”

Meagher’s rhetoric resonates with contemporary language, and rebuffs current attacks on immigrants today by American nationalists.

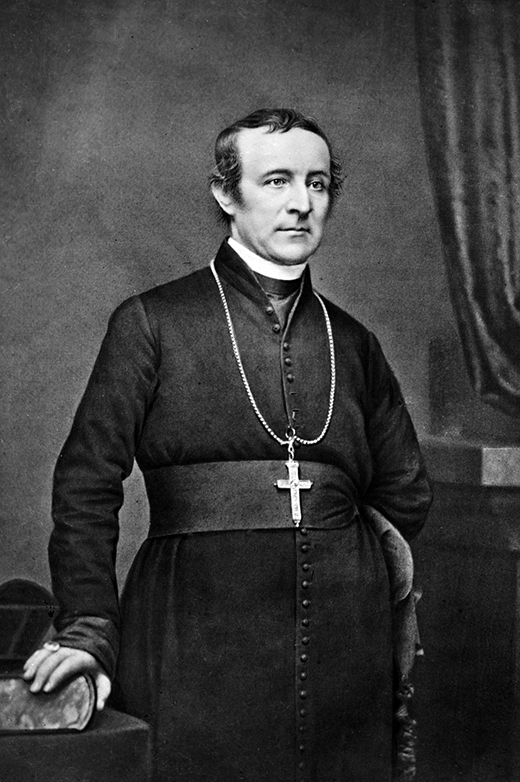

Archbishop John Hughes, in his March 17, 1853, oration at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, turned to the condition of the Irish immigrant community in America: “Wherever they are found…not only do they cherish fond memory for the apostle of their native land, but they propagate it, and make the infection as if it were contagious, so that those who would not otherwise have had any knowledge of St. Patrick become thus desirous to enter into those feelings, and to join in celebrating their anniversary festival of the apostle of Ireland.” Earlier Hughes had confronted Jacob Aaron Westervelt, the anti-immigrant mayor of New York, warning that if one Catholic church was attacked by rioting Nativists, the city would be turned into a “second Moscow” (Russians burned Moscow to the ground in 1812 rather than let Napoleon occupy it.)

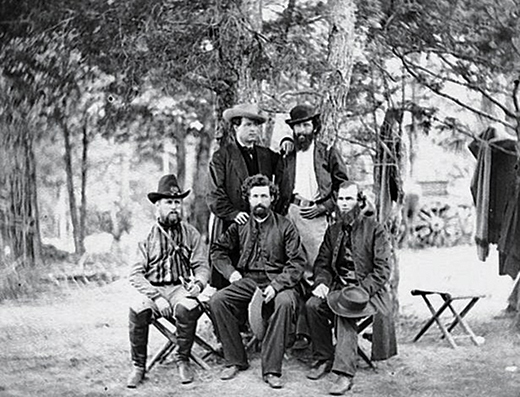

The Fighting 69th had the designation of being the first regiment in the Irish Brigade, formed by Meagher at the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861.

The brigade fought with courage and discipline, despite suffering the highest casualty rate of any Union brigade during the Civil War. The Irish had already distinguished themselves in the American revolutionary war.

When the shot heard round the world was fired, 147 Irishmen were among the minutemen at Lexington and Concord. After the smoke cleared on April 19, 1775, 22 Irishmen had given their lives in America’s bid for independence.

General George Washington proclaimed March 17 a day of rest for his Continental Army in 1780, acknowledging the cause of Irish freedom and the Irish-American alliance against the British Empire. Americans were not going to allow themselves to be ruled as Ireland was.

Forty-five percent of Washington’s Continental Army was Irish. Alan Lomax, American folk song collector, observed:

“If soldiers’ folk songs were the only evidence, it would seem that the armies that fought in the early American wars were composed entirely of Irishmen.”

The Irish, skilled at verbal arts, raised a glass to toast their dual identity at the centennial celebration of Boston’s Charitable Irish Society, March 17, 1837: “To Ireland and America. May the former soon be as free as the latter, and may the latter never forget that Irishmen were instrumental in securing the liberty they now enjoy.”

In the Siege of Yorktown sequence of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s smash hit musical, Alexander Hamilton asks: “How did we know that this play would work? We had a spy on the inside. That’s right!” The chorus shouts: “Hercules Mulligan!”

Mulligan, an Irish-born tailor and agent of the Patriot’s spy network, replies:

“A tailor spyin’ on the British government!

I take their measurements, information and then I smuggle it.

To my brother’s revolutionary covenant.

I’m runnin’ with the Sons of Liberty and I am lovin’ it!”

The morning after the British evacuated New York City, November 26, 1783, General Washington invited Mulligan to breakfast. Soon the city was returned to the victorious Patriots and declared the capital of the United States.

Before the American Revolution there had been little attempt by either Ireland or America to actively champion the cause of the other. That all changed after Benjamin Franklin visited Ireland. Franklin cherished the filial tie with England but reluctantly resigned himself to breaking it after he witnessed the wretched conditions under which the Irish lived. He believed that after almost six centuries of British rule and conquest, the Irish were faced with the possibility of total extinction.

In April 27, 1769, Franklin wrote to his fellow patriots in Massachusetts: “All Ireland is strongly in favor of the American cause. They have reason to sympathize with us.”

John J. Cosgrove lectured the American Historical Society in 1910: “I assert tonight without fear of contradiction from any historian American or English that the blundering unjust, and criminal acts of England in Ireland, and especially in the province of Ulster, did more to fill the armies of George Washington with brave soldiers than almost any other cause.”

Lord Mountjoy lamented in Parliament on April 2, 1784: “America was lost by Irish emigrants… I am assured from the best authority, the major part of the American army was composed of Irish and that the Irish language was as commonly spoken in the American ranks as English. I am also informed it was their valor that determined the contest. “

After Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia, on October 19, 1781, legend has it that during the surrender ceremonies, the British regimental band played the familiar march, “The World Turn’d Upside Down.” It was the Irish in the Continental Army who accelerated the pace of that downward turn.

Irish participation in the American Revolution helped give birth to a new nation. The American-Irish returned the favor after the 1916 Easter Rising when, “Ireland…supported by her exiled children in America…strikes in full confidence of victory.” Ireland’s war of independence ended with the Anglo-Irish Peace Treaty in 1921 and, “Ireland, long a province, A Nation once again!” Erin go Bragh! America forever! ♦

Leave a Reply