New York Official Uses Investment Power to Promote Human Rights

Patrick Doherty recalls one of many St. Patrick’s Day parties on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where his parents met, and his grandparents still lived when he was young.“The parade in those days ended at 96th Street. So, each year my grandmother basically invited the whole parade back to their apartment,” Doherty said, seated behind his desk at the downtown Manhattan office where he works as New York State comptroller Thomas DiNapoli’s director of corporate governance. The extended Doherty clan was active in social circles with ties to Derry City, where Doherty’s father and grandfather (just two in a long line of boys in the family named Patrick) were born. A photograph from one particular St. Patrick’s Day parade party made its way across the Atlantic and into the Derry Journal newspaper. When young Pat Doherty later studied that newspaper, his eyes were drawn less to the photo of revelers in his grandparents’ apartment, and more to the stamp on the envelope that brought the paper to New York. “I was a precocious six-year-old, so I said to my grandfather, ‘We’re Irish – so how come the Queen of England’s picture is on the stamp?’ That’s when my grandfather sat me down and explained partition to me.”

This was the beginning of what would later become a career focus on Northern Ireland. The personal, for Pat Doherty, became not just political, but professional, even historical. Ultimately, Doherty played a key role in the build-up to the Good Friday Agreement, and what has since become two decades of sometimes fragile but ultimately lasting peace in Northern Ireland. For playing a central role in implementing what came to be called the MacBride Principles, a corporate code of conduct for companies doing business in Northern Ireland, Doherty has earned induction into the Irish America Hall of Fame.“It’s very heartening,” Doherty says of the honor. “I’ve been working on this issue since 1984… Persistence in life is always the key. You have to stick with it.” Those who worked by Doherty’s side said persistence is just one of the many attributes which made the passage and implementation of the MacBride Principles possible. “One would be very hard-pressed to find another leader with as much knowledge and dedication…on matters of great importance to the Irish-American community,” recalls John Dearie, a longtime New York state lawmaker and, for his own contributions to the Northern Ireland peace process, a 2019 Irish America Hall of Fame inductee.

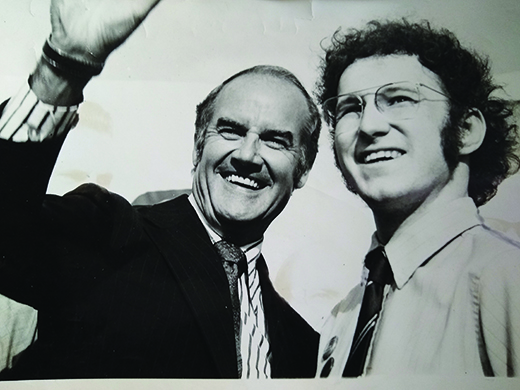

in 1972.

He entered the political game while still in college, working on the George McGovern presidential campaign in 1972, and serving as a delegate at the Democratic National Convention. He also worked with Democratic presidential candidates in 1976, and again in 1980 for Irish American Ted Kennedy. Doherty graduated from Hofstra University, and went on to study International Affairs at Columbia University where a campus visit from Bernadette Devlin McAliskey rekindled his interest in human rights issues in Northern Ireland – something that would stay with him as he went on to pass the New York State bar exam and find work as a public official. He began his career working for the New York State legislature, where he learned the nuts and bolts of how laws were passed, knowledge that would come in handy when he landed a position with the New York City comptroller’s office, and help earn him a place in the history of the Northern Ireland peace process.In hindsight, it might seem a role Doherty was born to play. His grandfather fought in the Irish War for Independence in his native Derry, eventually serving time in both British and southern Irish prisons.

“When he got out, he saw what the employment situation for nationalists in the North was,” recalled Doherty. He decided to emigrate to America with his young family, including Doherty’s father. Doherty’s own father, brought to New York at age three, went on to serve in World War II, and settled on Long Island to raise a family. But for all of the lessons Doherty may have learned about partition from his grandfather, it was a different conflict – thousands of miles from Northern Ireland – that gave inspiration to Doherty, as well as Irish-American activists, in the mid-1980s. By that time, an African-American civil rights activist named Leon Sullivan had devised a unique way to pressure the government of South Africa, which enforced a racially separatist system known as apartheid. What came to be called the Sullivan Principles were designed to ensure that American corporations invested only in South African companies that also fought discrimination.

Various Irish and Irish-American groups, most notably Fr. Séan McManus and the Irish National Caucus, had been agitating on the employment issue in Northern Ireland. And Doherty, then working for New York City comptroller Harrison Goldin, was asked to respond to a letter to Goldin from a constituent living in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, at the time a heavily Irish neighborhood.

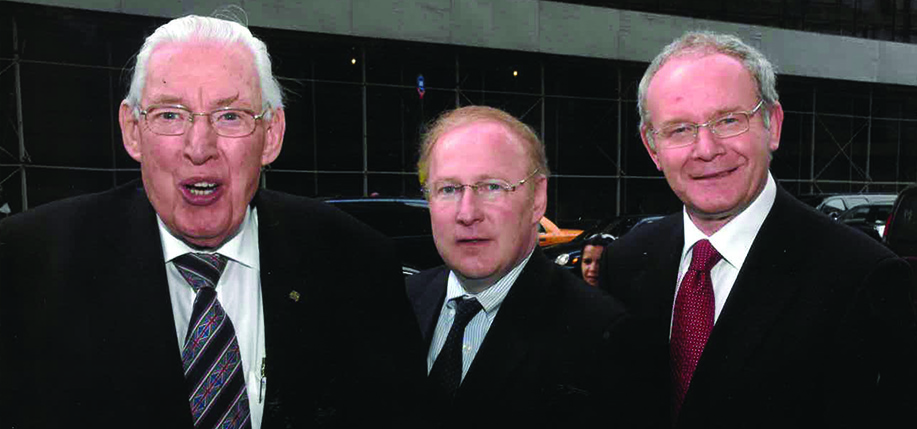

his brother Kevin, and their grandmother in the 1960s.

“They probably sent it to me because I was the new Irish guy in the office,” Doherty recalls with a laugh, adding: “The letter basically said, ‘It’s good you’re endorsing the Sullivan Principles for South African investments. Why not do the same thing to fight discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland?’” Doherty and others in the comptroller’s office formulated a series of “principles” which linked American investment to anti-discrimination initiatives. Doherty then sought out prominent figures in Irish political circles from varying political backgrounds, enticing them to join a campaign to support these guidelines. Irish statesman and international human rights activist Sean MacBride – a Nobel Peace Prize-winner and founding member of Amnesty International – agreed to “lend his name and prestige to the effort” to link American investment to anti-discrimination initiatives. Billions of dollars in public and private investments would come to be tied to fighting anti-Catholic discrimination in the North.Though many cities and states ultimately signed on to support the MacBride Principles, there was no initial guarantee they would have such a positive impact.

In 1985, the New York Times dubbed them “lofty but misguided.” The influential paper editorialized: “The danger is that such exertions could make matters worse. With an unemployment rate of 21 percent, Northern Ireland desperately needs more investment, not less. Adding an American anti-discrimination law to Britain’s is unnecessary and would surely deter the new investors. These interventions from afar would only add to Ulster’s agony.” John Dearie recalls: “This ran into tremendous opposition, particularly in the [New York] State Senate. The feeling was: ‘Why should we restrict these investment decisions?’ Pat was enormously helpful in overcoming that opposition.” Doherty, Dearie, and others held firm in their belief that the MacBride Principles could lead to significant progress during what were some of the most tense days of Northern Ireland’s “Troubles.” It was just a few years after the hunger strikes of 1981. The early 1980s saw an average of over 100 annual deaths due to the ongoing conflict. Irish Americans were deeply stirred by these events and the MacBride Principles campaign gave them a vehicle to press for significant change. The MacBride Principles also highlighted the central role that Irish Americans were ready to play in the peace process.

Many people in the North were skeptical about their chances for success. “Americans sometimes approach things differently – with more of a ‘can do’ attitude. It’s not ‘Can we do this?’, but ‘How do we get this done?’”Doherty also found that people in the North were sometimes more willing to engage with Americans than they were with each other. “The key was that men and women on all sides of the divide talked to us, and were anxious to tell their story,” Doherty recalls. In the end, the MacBride Principles campaign successfully galvanized Irish Americans, helping to pave the way for the peace process and the Good Friday Agreement.Looking back on his many trips to the North at the height of the Troubles, Doherty expresses a mixture of amazement and relief. There were particularly tense moments amidst the bonfires of the July marching season, as well as late-night trips to pubs well known for their patrons’ hard-liner stances. But these visits proved to many that Doherty and other Irish Americans were serious about making progress in the North.“Discrimination was rampant and systemic,” recalls Doherty. “There was virtually no enforcement. The anti-discrimination laws were a joke.”The MacBride Principles were able to succeed, Doherty believes, because they “had teeth.” They were far more substantive than merely passing strongly worded but ultimately superficial resolutions. There were specific incentives for companies to abide by the principles, and penalties for not doing so. Doherty notes, “Catholics in the North were two-and-a-half times more likely to be unemployed. When we talked to some British officials about this they would say things like, ‘Well, [Catholics] lack the Protestant work ethic.’”

But once the MacBride Principles were enacted, Doherty and others kept a close eye not just on American investments, but hiring practices and employment figures in the North.“The key part of all this was that progress had to be institutionalized and today the unemployment rate differential between Catholics and Protestants has virtually disappeared, and one of the chief reasons is that Irish America ushered in the MacBride Principles,” said Doherty. Doherty also believes the principles had such a substantial impact because they did not address the national question directly, but rather attacked the systemic discrimination against nationalists that was one of the root causes of the Troubles. “We were promoting fairness and equality.”

Meanwhile, if Doherty has learned anything after nearly four decades monitoring issues related to Northern Ireland, he’s learned to expect the unexpected. In 2016, Northern Ireland emerged as a complicated but central player in the broader and bitter debate over “Brexit” – Great Britain’s exit from the European Union. As Doherty notes, it may well be that Brexit will bring about something many Irish Americans have been waiting for – a united Ireland. “The North voted overwhelmingly to remain in the European Union,” says Doherty. As he sees it, the economic, social, and political dislocations that will arise from Brexit, combined with shifting demographics and a younger population whose views on history are not as hardened, may lead to a border vote for unifying Ireland and thus rejoining the E.U. Summing up, Doherty says, “The legacy of the MacBride Princlples campaign is threefold: one, it was successful in helping to end the systemic employment discrimination against Catholics that had existed since partition; two, it highlighted the critical importance of the American dimension in resolving the conflict, and helped lead to the critical American interventions during the Clinton administration; and lastly, and perhaps most important, it helped to demonstrate to many people in Ireland that non-violent political action could bring about significant change.”

I would like to send an email to Patrick Doherty about Fenian Bonds, a topic of which he knows considerable. I am interested in Fenian bonds for an article I am writing for the New York Irish History Roundtable.

The email I had for him is no longer valid since his retirement from the NY Office of Comptroller in late 2020. Would you know how I might reach him?