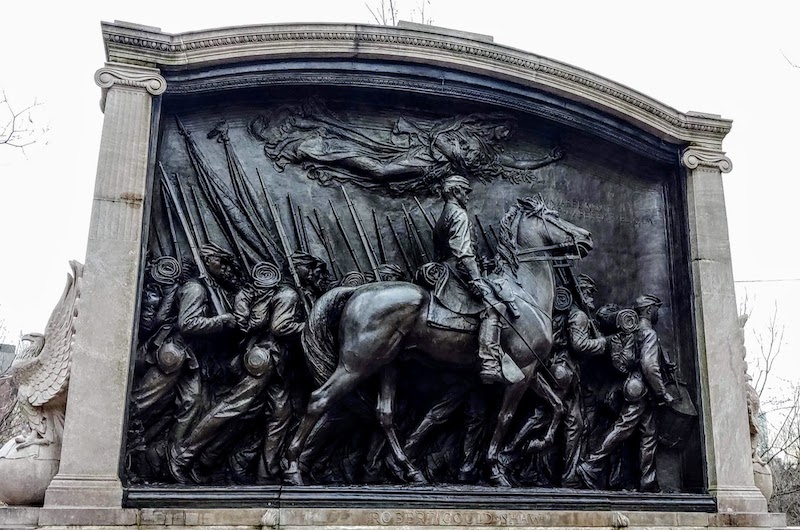

Pictured above: The Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts Fifty-Fourth Regiment is a bronze relief sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

You aren’t in Boston long before realizing what an Irish city it is: Logan Airport, Callahan Tunnel, the McCormack, Kennedy, Moakley and O’Neill federal buildings, plus numerous parks, boulevards and squares honoring Irish Bostonians. The Irish have been in Boston for centuries with an illustrious history dating from colonial times through the present.

So it’s not surprising that Boston has an Irish Heritage Trail spanning three centuries and including politicians and war heroes but also artists, writers, labor leaders and athletes. The Boston Irish Heritage Trail joins the city’s other popular walking trails such as the Freedom Trail, Black Heritage Trail, Immigrant Trail and Women’s Heritage Trail as a novel way to experience the history and ambiance of Boston.

The Irish Trail lists 20 Irish memorials, statues, cemeteries, parks and buildings in Boston’s downtown and Back Bay, covering about 3.5 miles, and another 20 landmarks in the city’s neighborhoods like South Boston and Charlestown.

Details of the Boston Irish Heritage Trail are available at www.irishheritagetrail.com. Here is an overview of some of the sites along the way, arranged by subject.

REVOLUTIONARY IRISH

The Irish played an important role in America’s Revolutionary War, especially here in New England. The Old Granary Burying Grounds on Tremont Street in downtown Boston, about two blocks from City Hall, has a number of important Irish Revolutionary War figures buried here. Among them is James Sullivan (1744-1808), lawyer, orator and statesman. The son of indentured Irish immigrants, Sullivan was a delegate to the Continental Congress and governor of Massachusetts in 1807. Other notable Irish buried here are Robert Treat Paine (1731-1814), a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and William Hall (d. 1771), a founder in 1737 of the Charitable Irish Society, the nation’s oldest Irish organization.

Perhaps the most popular Irish immigrant buried at Old Granary is Patrick Carr, who was one of the five men shot by British troops on March 5, 1770 in an episode that jumpstarted the American Revolution. Carr, described as a sailor and as a leather maker, was the last to die from the scrimmage and was buried on St. Patrick’s Day in 1770.

Carr and the others are memorialized at the Boston Massacre Memorial, on Boston Common along Tremont Street, next to the Visitor Information Center. Unveiled in 1888, the Memorial unveiling included a poem written by Irish rebel John Boyle O’Reilly for the occasion. And a cobblestone circle next to the Old State House at 15 State Street marks the actual spot where the massacre occurred.

Governor Sullivan’s brother, Brigadier General John Sullivan (1740-1795), was George Washington’s point man during the British evacuation of Boston in March 1776; the password used that day was St. Patrick. General Sullivan is honored at the Dorchester Heights Memorial in South Boston, erected in 1902.

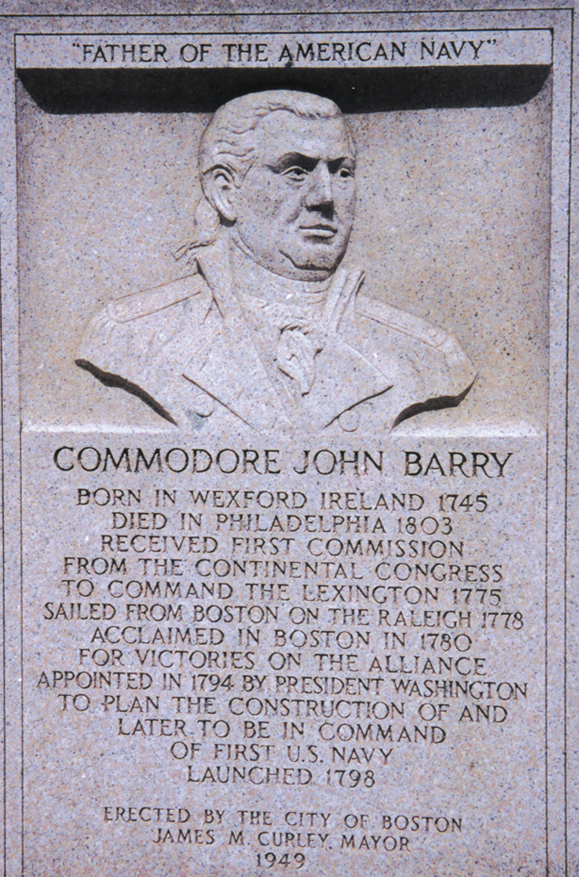

On Boston Common along Tremont Street is a memorial to Commodore John Barry (1745-1803), a Revolutionary War naval hero many consider to be the Father of the American Navy. Born in County Wexford, Barry won the first and last naval battles of the Revolutionary War, and Washington appointed him the first Commodore of the US Navy. The original memorial to Barry, unveiled by Mayor James M. Curley in 1949, was stolen by vandals in the 1970s, recovered, and is now located at the Charlestown Navy Yard next to the USS Constitution.

John Singleton Copley (1737-1815) was born in Boston, the son of Irish immigrants from County Clare. Copley is considered America’s first great portrait artist, having painted John Hancock, Samuel Adams, Paul Revere and other leading citizens. The Museum of Fine Arts has over 50 Copley paintings, including the famous Paul Revere portrait. Copley Square Park in Boston’s Back Bay is named in his honor, and in 2002 the city of Boston unveiled a statue of Copley, paintbrush in hand.

THE FAMINE IRISH

Ireland endured many famines during the 19th century, causing Irish families to emigrate. The worst famine, known as the Great Hunger, occurred between 1845-49, ultimately killing one million people. Over 100,000 Irish refugees arrived in Boston Harbor during this time, transforming the city.

A century and a half later, Bostonians commemorated the Great Hunger by erecting the Irish Famine Memorial on June 28, 1998 at the comer of School and Washington Streets near Downtown Crossing. The twin sculptures by artist Robert Shure depict a starving family in Ireland and a hopeful family making their way in America. Eight narrative plaques encircling the statues tell the story of the famine and connect it to modern famines still occurring around the world today.

Across the Charles River in Cambridge Common outside of Harvard Square is the Cambridge Irish Famine Memorial, created by Derry artist Maurice Harron. Unveiled in July 1997 by Mary Robinson, then-president of Ireland, the memorial shows an Irish woman holding her dead infant while waving to her two other children to flee their home.

On Deer Island in Boston Harbor, a temporary memorial to the Irish was placed in 1997 at the New Rest Haven Cemetery, where about 800 Irish Famine refugees who were quarantined on the island (1847-1849), died and were buried. In May 2019, a permanent memorial was unveiled atop Deer Island, which today is the region’s wastewater treatment facility.

South of Boston, the Brig St. John Memorial in Cohasset commemorates the tragic shipwreck in October 1849, when over 80 Irish men, women and children fleeing the Famine drowned when their ship crashed off the Massachusetts coast during a storm. They are buried at Cohasset Cemetery beneath a 19-foot Celtic cross that over-looks Little Harbor in Cohasset.

IRISH SCULPTORS

The Great Hunger caused indescribable hardship and suffering, but also gave Irish immigrants a new freedom to express their talents in America. Two families from both ends of Ireland, the Saint Gaudens of Dublin and the Milmores of Sligo, fled to Boston to escape the Famine in 1848 and 1851 respectively. Their sons created a body of remarkable public sculptures that still stand today in many of the city’s most public spaces.

Augustus (1848-1907) and Louis Saint Gaudens (1854-1914) together and individually produced some extraordinary public memorials throughout Boston and indeed the United States and Ireland. Their father was a French shoemaker and their mother, Mary McGuinness, was a native of County Longford. The family fled Dublin in the summer of 1848 and arrived in Boston in September.

Augustus is the more famous of the brothers, and became the most acclaimed sculptor of his generation, producing over 150 sculptures, the most notable being the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial in front of the Massachusetts State House, a pageant to Boston’s Black Civil War 54th Regiment. The Shaw Memorial is also featured on the city’s Black Heritage Trail.

Augustus also created the Phillips Brooks statue alongside Trinity Church in Copley Square and the medallions over the entrances to the McKim Building at the Boston Public Library. His last piece was the memorial to Irish patriot Charles Stuart Parnell, located on O’Connell Street in Dublin.

Louis Saint Gaudens, born in New York City, collaborated with Augustus on many major projects during their careers. Louis created the twin Marble Lions on either side of the grand stairway in the McKim Building commemorating the Second and Twentieth Massachusetts Infantry Associations.

Joseph (1842-1886) and Martin Milmore (1844-1883) immigrated to Boston in 1851 from County Sligo. Martin attended the Boston Latin School, and his artistic talent was immediately recognized. At 16 he began an apprenticeship with Boston sculptor George Ball, who was completing the George Washington Statue in the Public Garden. Martin created a series of famous Civil War memorials, including the Sailors and Soldiers Memorial on Boston Common, unveiled in 1877, as well as the Roxbury Soldiers Memorial in Forest Hills and the Charlestown Soldiers Memorial.

His brother Joseph assisted him on the major projects, and is best known for the Sphinx at Mr. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, created as a Civil War memorial to Union soldiers in 1872 at a time when Egyptian art was fashionable in America. A third brother, James, helped out in the studio the brothers rented on Harrison Avenue in the South End.

Another sculptor featured on the Trail is John Donoghue, a Chicago Irish-American who was discovered by Oscar Wilde during his famous trip across America in 1882. Donoghue moved to Boston for a time, where he produced busts of John Boyle O’Reilly and Hugh O’Brien, the city’s first Irish mayor. Donoghue’s greatest work is considered to be Young Sophocles Leading the Chorus of Victory, which is located at the Isabella Steward Gardner Museum in the city’s Fens area.

THE KENNEDYS

No history of the Boston Irish is complete without the Kennedy Family, the First Family of Irish America. When the Kennedy and Fitzgerald clans united in 1908 through the marriage of Joseph P. Kennedy of East Boston and Rose Fitzgerald of the North End, they created a political dynasty that continues today.

As President John F. Kennedy poignantly noted during his visit to Ireland in 1963, “Eight of my grandparents left these shores in the space almost of months and came to the U.S.”

The Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Garden, located at Columbus Park on Atlantic Avenue in the North End, is a tribute to the matriarch of the clan, Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy (1890-1995), whom many consider to be the consistent strength behind the family during the Kennedy years. The garden, built in 1987, features a wonderful array of roses each spring planted by the Boston Parks Department, and an inscription honoring Rose “for her contributions to this country, and to the inspiration she has given to us all.” She was born at 4 Garden Court in the North End. In 2008, the City of Boston added the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway, a 27 acre swath of greenway running from the North End to Chinatown, along Boston Harbor.

A plaque to John F. Fitzgerald (1863-1950), Rose’s father and mayor of Boston in 1906 and again in 1910, was placed across from Haymarket train station and stands at the corner of the Rose Kennedy Greenway and Hancock Street in the North End.

The President John F. Kennedy Statue on the front lawn of the Massachusetts State House along Beacon Street shows a youthful JFK strutting purposefully, hand in pocket. It was created by artist Isabel MacIlvain and unveiled in 1988 by his family and friends. Beyond downtown, must-visits include the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum in Dorchester, which is the president’s official library. The library has a powerful news clip of President Kennedy’s famous trip to his ancestral village in Wexford in 1962, and contains many Irish artifacts that Kennedy cherished during his life. The John F. Kennedy Birthplace at 83 Beale Street in Brookline, managed by the National Park Service, has Kennedy memorabilia and offers guided tours.

WAR HEROES

The American Civil War was the first great opportunity for the Famine generation to demonstrate their patriotism to their new country, and Massachusetts’s Irish soldiers heeded the call to arms. In Boston’s Public Garden stands a memorial to Colonel Thomas Cass, who led Boston’s Ninth Irish Regiment, composed mainly of Irish immigrants who had survived the anti-Irish Know Nothing period of the 1850s. The regiment of 1,022 men mustered in 1861 and fought gallantly in a number of important battles. Cass, a native of County Laois and a member of the School Committee, was mortally wounded at Malvern Hill in Virginia, and died in Boston. His memorial was unveiled in 1899, attended by members of the Ninth Regiment.

The Irish Flag Display at the Massachusetts State House features various flags used by the 9th Irish Regiment and the 28th Irish Regiment of Massachusetts, part of a collection of nearly 500 military flags from the American Civil War. The Ninth Regiment flag was made of green silk with a scroll inscribed in gold that read: “Thy sons by adoption; thy firm supporters and defenders from duty, affection and choice.” These can be viewed at Memorial Hall in the main rotunda.

Another famous member of the Ninth Regiment was General Edward L. Logan (1873-1939), for whom Boston’s Logan International Airport is named. The son of Lawrence J. Logan of Ballygar, Galway, Edward fought alongside his father in the Spanish American War of 1898 with the Ninth Regiment, and later commanded the Yankee Division during World War I. He represented South Boston in the state house and was later a municipal judge in Boston.

POLITICIANS

The Irish came to dominate local and state politics for much of the 20th century, holding the Boston mayor’s office for 86 years of the century, and from 1929 to 1994 without interruption. The 19th century produced one Irish mayor, Hugh O’Brien (1827-95), a Cork native whose family immigrated to Boston when he was five. O’Brien was a successful businessman before becoming mayor from 1884-88, during which time he presided over the expansion of the city’s Emerald Necklace park system and laid the cornerstone for the new Public Library at Copley Square. A bust of O’Brien by sculptor John Donoghue is located at the Boston Public Library.

Patrick Collins (1844-1905) was Boston’s second Irish-born mayor (1902-05) and the first Catholic congressman from Massachusetts (1871). Born near Fermoy, County Cork, he immigrated to Boston in 1848 with his widowed mother and siblings. A leading spokesman for the Fenian movement, he was also president of the Land League in the USA. He got his law degree from Harvard while studying nights at the Boston Public Library and working by day as an upholsterer. He was the American Ambassador to Great Britain under President Grover Cleveland in 1892. Collins is memorialized on Commonwealth Avenue near Dartmouth Street.

James Michael Curley (1874-1958), Boston’s most notorious Irish politician, is honored with a small park facing Boston City Hall on Congress Street. The son of Galway immigrants, Curley served four terms as mayor between 1914 and 1949, and was also the governor and a Massachusetts congressman during his controversial career. His life was made into a movie, The Last Hurrah, based on a novel by Boston writer Edwin O’Connor and starring Spencer Tracy as Curley. The Curley Mansion, now owned by the city of Boston, is located on the Jamaicaway in Jamaica Plain and still features shamrocks carved into the green shutters on each window.

Maurice Tobin (1901-53), a protégé of Curley, grew up in Boston’s Mission Hill, the son of immigrants from Tipperary. He served as mayor from 1937-43, was Governor of Massachusetts in 1944 and U.S. Secretary of Labor under Harry Truman. The Tobin Memorial was unveiled in 1957 at the Hatch Shell along the Charles River Esplanade. The Tobin Bridge coming into the city from the North Shore is also named in his honor.

Across the lawn on the Esplanade is a memorial to David I. Walsh (1872-1947), the first Irish-Catholic governor of Massachusetts from 1914-16. He was also Lieutenant Governor and the first Catholic Senator from Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress, a post he held for 20 years. A strong supporter of women’s right to vote, Walsh was also an ardent Irish nationalist, serving as the key speaker at a rally for Irish hero Eamon de Valera at Fenway Park in 1919. The Walsh memorial was unveiled in 1954.

MORE FAMOUS IRISH

Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore (1829-92), born in Ballygar, Galway, is best known as the composer of the Civil War anthem, “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.” He emigrated to Boston in 1848, and at once established himself as a coronet player and band leader. In 1855 he began the tradition of an annual Fourth of July concert on the Boston Common, a forerunner to the Boston Pops on the Esplanade. Gilmore was also a successful promoter. He staged two giant peace jubilees near Copley Square in 1869, attended by President Ulysses S. Grant, and again in 1872, which featured waltz king Johann Strauss and 20,000 performers.

Louis Sullivan (1856-1924), whose father Patrick was an Irish dance master from Cork and whose mother was Swiss French, was born at 22 Bennett Street off of Washington Street in the South End. A plaque honors his birthplace, placed there by the Boston Society of Architects. Sullivan is recognized as the father of modern architecture, and was the mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright. His most famous dictum was `form follows function.’

Mary Kenny O’Sullivan (1864-1943) was a nationally acclaimed union organizer, originally from Hannibal, Missouri, the only child of Irish immigrants. After organizing workers in Chicago, she moved to Boston in 1893 and organized the city’s shoemakers and garment workers, and also helped found the National Women’s Trade Union in New York City. O’Sullivan is one of six Massachusetts women commemorated at a State House portrait gallery entitled Hear Us, unveiled in 1999, and located next to Doric Hall.

John Boyle O’Reilly (1844-90) was perhaps the greatest Boston Irishman of the 19th century, a dashing, larger-than-life figure who reached Boston in 1870 after escaping from a British penal colony in Australia. O’Reilly became editor of The Pilot and published numerous editorials defending the fights of immigrants, blacks and children working in factories. He was poet laureate of Massachusetts, an avid sportsman, orator and a staunch advocate of Irish freedom from Britain. His memorial in the Fens was created by artist Daniel French in 1896, and is considered one of the best public sculptures in Boston.

The daughter of Irish immigrants and orphaned at eight, Annie Sullivan (1866-1936) taught Helen Keller to read, see and speak. Sullivan, who was partially blind herself, learned to read and write at the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston. In 1960 Keller herself placed a plaque in Braille and English, in Cambridge near the comer of Brattle and James Streets, next to a small fountain, that reads “In memory of Annie Sullivan, teacher extraordinary.”

James Brendan Connolly (1868-1957) of South Boston was the first gold medal winner in the modern Olympic Games, winning the Triple Jump competition in Athens in 1896. “This one’s for Galway,” he reportedly shouted before making his winning jump. Connolly later became a noted writer and penned over 50 novels about the sea. His memorial is at Columbus Park in South Boston.

Born in South Boston to Irish immigrant parents, Richard Cardinal Cushing (1895-1970) was a leading churchman of the 20th century. He preached universal brotherhood among all religions, befriended Jewish leaders, and raised money for foreign missions. He officiated at the wedding of John and Jacqueline Kennedy and also presided at JFK’s funeral mass in 1963. Cushing Park is at the Corner of Cambridge and New Chardon Streets near Boston City Hall.

BURIAL GROUNDS

While 18th century Irish are buried in downtown cemeteries then reserved for Protestants, a number of new cemeteries sprang up in the 19th century as Irish Catholics began coming here in greater numbers. St. Augustine’s Cemetery in South Boston is the oldest Catholic cemetery in Boston, created in 1818. Other 19th century cemeteries for the Irish include Bunker Hill Cemetery in Charlestown, Cambridge Catholic Cemetery in North Cambridge, and Holy Cross Cemetery in Malden.

Fanny Parnell (1848-82), founder of the Women’s Land League and sister to Charles Stewart Parnell, is buried at Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, as is Colonel Thomas Cass. Heavyweight boxing champ John L. Sullivan (1858-1918) is buried at Old Calvary Cemetery in Roslindale. Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953), Nobel Prize winner in Literature, is buried at Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, as are the Milmore brothers, who sculpted numerous Civil War monuments. Rose Kennedy (1890-95) and Joseph P. Kennedy (1888-1969) are buried at Holyhood Cemetery in Brookline, along with John Boyle O’Reilly, Patrick Collins, Maurice Tobin and Hugh O’Brien. Buried at St. Joseph’s Cemetery in West Roxbury are mayors John F. Fitzgerald (1863-1950), John B. Hynes (1897-1970), John Collins (1919-1995), U.S. House Speaker John W. McCormack (1891-1980) and Mary Kenny O’Sullivan.

PLACES TO STUDY THE IRISH

Boston College Irish Studies Program (617-552-3938) offers numerous degrees and courses in Irish history, literature, politics and music; the John J. Burns Library contains valuable manuscripts of W.B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, Irish tenor John McCormack and also the prized Seamus Connolly Collection of Irish Music. Harvard University Celtic Languages and Literatures Department (617-495-1206) offers advanced study in the Irish language; the Widener Library contains an important collection of Irish materials. University of Massachusetts (617-287-6752) and Stonehill College (508-565-1000) also boast excellent Irish Studies programs.

The Boston Public Library (617-536-5400) at Copley Square has a renowned collection of over 13,000 Irish items, including original documents from the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the creation of the Irish Free State, and the formation of Dublin’s Abbey Theater. The New England Historic Genealogical Society (617-536-5740) on Newbury Street has important records of Irish families dating back to colonial times. The Massachusetts Historical Society (617-536-1608) on Boylston Street holds the records of the Charitable Irish Society from 1737-1925, and also has early paintings by John Singleton Copley and a sculpture by Martin Milmore. The Bostonian Society (617-720-1713) at 15 State Street has a rich collection of archives and photographs that relate to the Boston Irish. The Boston Athenaeum (617-742-9600) at 10 1/2 Beacon Street has numerous collections relating to the Boston Irish. In Milton, the Captain Forbes House Museum (617-696-1815) on Adams Street has an important collection of artifacts from the USS Jamestown voyage from Boston to Cork in 1847, which carried food and relief supplies to starving Irish.

If You Go…

The Boston Irish Heritage Trail can be downloaded at www.irishheritagetrail.com. The Boston Irish Tourism Association offers guided tours of the Trail.

To learn about Irish activities in the area, visit www.irishmassachusetts.com.

Leave a Reply