Ladies: who among us hasn’t at least briefly entertained the fantasy of having Catherine Deneuve portray you in the movie of your life? Okay, even if that’s not the direction you would go casting-wise, know that one Margaret Kelly had that distinct honor. Catherine Deneuve played a character based on her in the classic François Truffaut film, The Last Metro (Le Dernier Metro). Set in Paris during the Nazi occupation, Deneuve’s Marion Steiner is the owner and leading lady of a theater who fights to keep the show going while also hiding her Jewish husband from the Gestapo. This drama faithfully retells two very tumultuous years of Margaret’s life with one exercise of artistic license: Unlike Marion, Margaret wasn’t French, she was Irish.

Margaret was born in Dublin’s Rotunda Hospital in 1910. Two days after her birth, her feckless parents, Margaret, Sr., and James Kelly, with a quick “Slán” and a vague claim about sending for the baby, took off. No one believed they would return, so a local priest handed her over to a religious family invariably known as “the three Murphy spinsters,” who doted on the newborn. The eldest and most devoted, Mary Murphy, a housekeeper, and seamstress, took charge of the baby.

Concerned by Margaret’s poor health, Mary Murphy took her to a Dublin doctor. Upon looking into her bright blue eyes, he shouted, “You’re my little Bluebell!” and the moniker stuck for the next 90 years. Ever protective, Mary Murphy was alarmed when the 1916 Easter Rising left Dublin in chaos. With Ireland’s chronic poverty causing the highest child mortality rate in Europe, she promptly whisked Bluebell away to Liverpool.

In Liverpool, she found work doing the cleanup in a hospital ward and enrolled Bluebell as a day student in a convent school. Another doctor recommended dance lessons to strengthen Bluebell’s spindly legs, quite a financial stretch for the single surrogate mother. But Bluebell, only eight years old, drew on the entrepreneurial spirit that would make her both world-famous and very rich. To help pay for the lessons, she delivered milk, dug potatoes, and worked as a golf caddy.

She made her stage debut at 12, and within two years left the nuns to join a dance troupe with a jaunty name, The Five Hot Jocks. Soon another, much classier troupe, The Jackson Girls, recruited her, and she joined the line of high-stepping gals, touring Europe for five years. A scout for the Folies Bergère took in a show and took in her legs, so much longer than those of French girls.

In 1932, Bluebell, as the saying goes, hit the big time. The Folies hired her as a chorine and choreographer but soon recognized a unique talent and asked her to form a troupe within their troupe – the eponymous Bluebell Girls were born. Bluebell, only 22, faithfully wrote Mary Murphy, sending her money and pictures from the Folies review. The still-devout spinster immediately got busy painting brassieres and underpants on the dancers, just in case a neighbor or the parish priest dropped by.

Bluebell found herself in a feud with the Folies headliner, Mistinguett. The legendary diva, now pushing 60 and still recovering from being dumped by Maurice Chevalier, was threatened by her much younger, much leggier co-star. Refusing to compete with a shrieking prima donna, Bluebell moved to the Paramount Cinema and formed another troupe, Les Blue Bell Paramount Girls. They performed during the intervals between films and became so popular that they were cast in movies, and were now high-kicking both on the stage and up on the screen.

Two years went by, and with Mistinguett muzzled, the Folies asked Bluebell to come back and gave her more autonomy. She was able to experiment with art direction, stage design, and elements of fantasy, most famously when her dancers surrounded Josephine Baker. Bluebell still maintained the Paramount troupe and formed a summer touring company – this was the beginning of her franchise, several troupes scattered over different countries. By 1938, she was the leading impresario of Europe’s most famous company of precision dancers.

She set the standard for the ideal Bluebell: 5’ 9” or taller with very long legs, preferably British, commitment to teamwork, and a background in ballet. The convent school girl was something of a Mother Superior, who demanded teamwork, discipline, and especially virtue from her girls. She absolutely forbade consorting with the clientele, saying, “I created chorus girls with class,” and would intercept billet-doux from the girls’ admirers and block stage-door-johnnies with her own body.

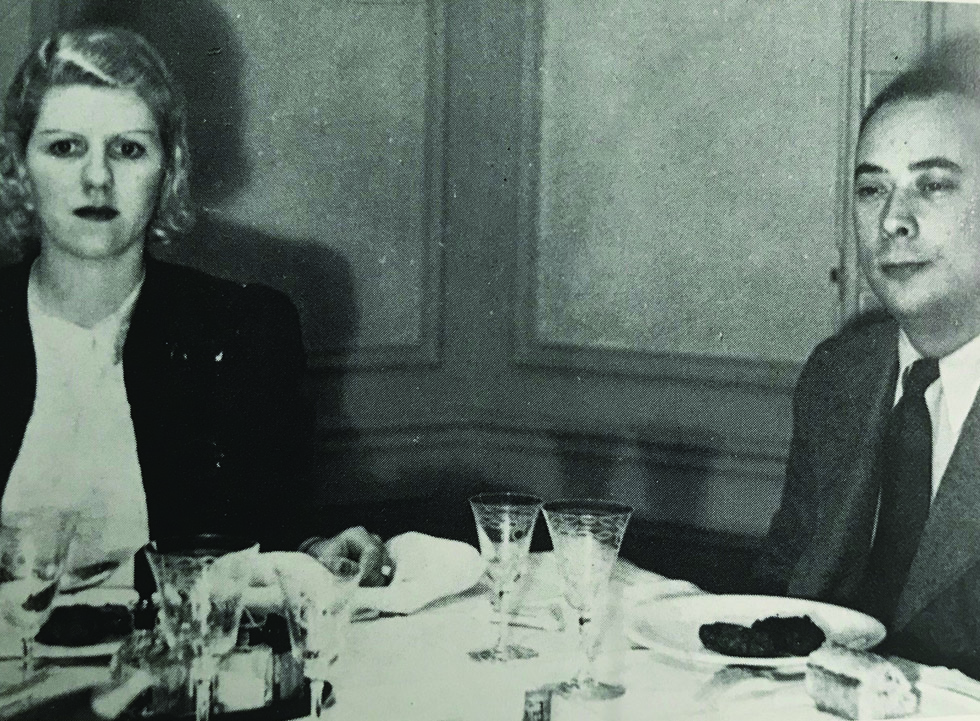

In 1939, she married Marcel Leibovici, a stateless Romanian Jew, composer, and pianist at the Folies Bergère. Marcel was also a savvy businessman who thought Bluebell and her dancers should have a presence in the growing cabaret scene. They formed a separate company for cabaret, a prescient move since during the Occupation, French (and German) audiences turned to cabaret.

Knowing the Nazis were storm trooping their way to France, the Leibovici’s, with their new baby, rushed to Bordeaux to get on the last boat to the U.K. Elbowed out by fleeing diplomats, they returned to the City of Light, now dark and silent, to wait. On June 14, 1940, France fell, Hitler’s army was in Paris and the following December, the Nazis were banging on the Leibovici’s door. They came not for the Jewish husband but instead for his wife, again pregnant, now condemned by her British passport.

Bluebell was sent to an internment camp, where she refused, as was her wont, to take any guff. When a prison guard gave her clean-up assignments, she announced, “I don’t do housework in my own home, and not going to start now.” Silence. She wasn’t shot, as expected, but excused from work detail, and later, at her insistence, the camp observed daily tea.

Back in Paris, a frantic Marcel went to the Irish legation, where he enlisted a now-forgotten character in Ireland’s history, the Minister Plenipotentiary to France, Count Gerald Edward O’Kelly de Gallagh. The count, as flamboyant as his name and title, appealed for Bluebell’s release on the grounds that she was a citizen of neutral Ireland. It worked, she was sprung and took some Sisters of Mercy with her.

A year later, it was Marcel’s turn to be arrested. In early 1942, he was rounded up in Marseilles and sent to a Jewish camp in the Pyrenees. Bluebell was now a pariah. Her former colleagues crossed to the other side of the street when they saw her coming; even the Folies, while asking her to choreograph a show, told her to stay away from the theater: they had their reputation to consider. But she continued to direct the cabaret, her sequined chorines offered a remnant of glamour to a city that reeked of defeat.

In the camp, Marcel reunited with a former music student, now in the French Resistance. The student helped him escape and Marcel made his way back to Paris and to Bluebell. For two-and-a-half years, she hid him in an attic, bribing the concierge, a known collaborator, with francs and eggs. Daily she heard the radio announcing that anyone who sheltered Jews would be summarily executed, and daily she rode her bike to Marcel, keeping him fed by scouring the black market and exhausting her ration card. She also managed to get pregnant…twice.

There’s a chilling scene in The Last Metro that re-enacted an incident in Bluebell’s life: the Gestapo hauls the wife in for interrogation; she keeps a cool façade, giving nothing away. But, unlike the movie character, Bluebell was seven months pregnant at the time. And if the Germans thought it unseemly that the wife with a missing husband was pregnant, they blamed libido à la française and not a spouse squirreled away in a nearby garret. The redoubtable Bluebell grew bolder – she refused to send a company of her dancers to Berlin, giving a wan excuse about upsetting relatives in the British army. She never had any relatives, anywhere, saving Mary Murphy, now over 80.

The war over, the Bluebell business was booming once again. Madame Bluebell was the artistic force and Marcel the financial manager when they brought the Bluebell Girls (and their male counterpart, The Kelly Boys) to the glittering Paris Lido. There they made show business history – they created the concept of the dinner show. Le Lido offered supper, dancing, champagne, and especially Bluebells in a spectacular floor show 365 nights a year. The Lido soaked the customers in overpriced drinks and supper and the show became Paris’s second-biggest tourist attraction, after the Eiffel Tower.

Madame Bluebell formed a partnership with a glitzy American producer, Donn Arden. Her tall beautiful dancers were now in scantier costumes, higher heels, and peacock tails as their flying kicks kept a frantic rhythm on the stage. Bluebells were wowing audiences all over the world, and their charms were not lost on Marcel. The hubby, stubby and short, got busy seducing the statuesque Amazons (Men!) and a deeply wounded Bluebell, recalling how she risked her life for him, forever distanced herself from him. But she never dismissed any of his paramours, probably realizing they were victims of a crime, then without a name – sexual harassment. Marcel died in a car crash in 1961 and was replaced in the organization by their eldest son, Patrick.

Bluebell found her greatest triumph in the Nevada desert when she and Donn Arden brought the Bluebells to the Las Vegas strip. Miss Bluebell caught Vegas fever, and her show exploded into an extravaganza that included live camels, jugglers, Roman gladiators, illusionists, ice skaters, strong men and, waterfalls. She sold out the Stardust Hotel and the MGM Grand where she later fought off its famous 1980 fire.

In the early 1960s, Miss Mary Murphy officially turned over her grave: the Bluebells went topless.

Bluebell rationalized, “If this is the way the world is going, I must go with it.” The dancers who chose to expose their breasts kept a distance from the audience and it was, as Bluebell said, a “celebration of the female body.” Nonetheless, an Arab sheik offered to buy the company, an Italian magnate upped the ante by offering 16 white Ferraris while Vegas mobsters merely got menacing, demanding the girls mingle with customers. Bluebell, having already faced down the Gestapo, would have none of it. All backed off when confronted with her wrath and her resounding, “Harrumph!”

Invariably thought of as British because of her Liverpool accent, she gave an interview to The Irish Times, saying, “I always felt Irish and always called myself an Irishwoman.” When asked if she ever searched for her parents, she would huff, “Why should I? After all, they never did anything for me.” But she finally admitted she did look for them. In Dublin, she obtained her birth certificate and went to the address her parents had given. She asked the landlord about a couple named Kelly and she recalled he made a sound like a snort, “Everyone around here is named Kelly.”

In six decades, she left a legacy that would have been extraordinary even for one who was both moneyed and mollycoddled, let alone a foundling who grew up in poverty. By sheer will, she recruited and trained 14,000 Bluebells, set up troupes over the world, received countless awards including the Legion d’honneur and the Order of the British Empire (OBE), had an audience with the pope, and was the subject of a book and BBC documentary. Today the proper woman once known as Margaret Kelly, beloved of Miss Mary Murphy, is part of a permanent Las Vegas exhibit named… SHOWGIRLS!

Toward the end, she lived in her Paris penthouse atop the Avenue Foch, and could still dance the can-can, lie about her age, and smoke a pack of cigarettes a day. She lived to 94 and the night after she passed, Le Paris Lido put together a fête, attended by four generations of Bluebells and Kelly Boys, the Irish and British ambassadors, and world press. They came to celebrate Madame Bluebell, who, everyone agreed, lived all the days of her life.

Margaret Kelly-Leibovici was buried in Cimetière de Montmartre, a bronze sculpture of her – in stern old age – stood atop her stone. Shockingly, graverobbers helped themselves to the bust, but the theft was fortuitous, a glass sculpture of a very young Bluebell was put in its stead.

A fan left this note:

Dear Margaret, your bust was stolen some years ago and these last weeks, a new – very new and modern – picture of you as a young beautiful dancer was placed on your grave. Behind you, a violinist is playing forever.

We love you, Margaret. You have inspired François Truffaut in his Last Metro. François is not very far from you in this same cemetery. Yours truly,

Oedipa aka Kay Harpa ♦

The Last Metro is my favorite Catharine Denueve film for her acting, glamor and the drama of the story. To learn its daring and courageous hero was a Wild Irishwoman is not only marvelous but absolutely miraculous–from abandonment to world fame and recognition! What a genius! What a life! loved the humor asides, too. Brava Rosemary Rodgers for great telling.

What a story ! What a woman ! What more can be said.

Thank you for publishing this story of a remarkable lady.

What I love about Irish America is learning all things that I never knew about before. Thanks so much for your enlightening articles.