The MacGillycuddy Reeks, Ireland’s tallest mountain range, stretches across the Iveragh Peninsula in the southwest section of the Emerald Isle. The area is steeped in ancient mythology and its scenic landscape is dominated by jagged, narrow spines cloaked in billowy clouds and flocks of sheep grazing in the glens below. Sadly, however, this picturesque setting also served as the location of a tragic accident involving American soldiers during WWII.

On December 17, 1943, a C-47 en route to England crashed in bad weather just below a mountain peak called Cnoc na Péiste (Irish for “Hill of the Serpent”). All five men aboard were killed. The aircraft and crew most likely would have taken part in D-Day – but more than seven decades later, the exact cause of the horrific event remains a mystery.

John O’Sullivan is a local guide who has lived his entire life at the foot of the “The Reeks.” Having traversed its vast network of trails hundreds of times, O’Sullivan holds a wealth of knowledge regarding these hallowed grounds: this familiarity includes the whereabouts of the infamous crash site, along with its well-hidden remnants still entombed on the mountain.

The C-47 “Skytrain” played a vital role throughout the war as a workhorse plane. The cargo transporter provided a wide range of duties such as carrying paratroopers, towing combat gliders, and delivering vital supplies – often behind enemy lines. The ill-fated journey of C-47A 43-30719 began with its delivery on October 10, 1943, at Baer Army Air Base in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Coincidentally, the field had been named for WWI ace, Paul Baer, who died in an airplane accident in 1931. A foreboding omen, indeed.

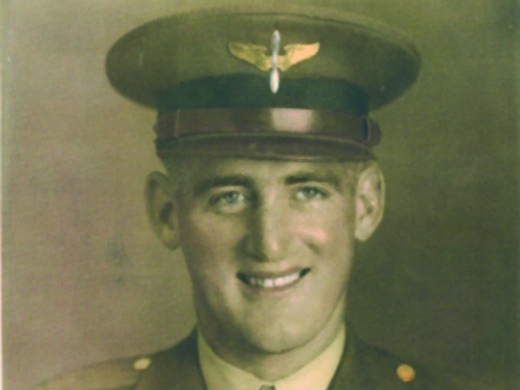

The flight crew comprised the following men: 2nd Lt. John L. Schwarf (pilot) of San Ardo, CA: 2nd Lt. Laurence E. Goodin (co-pilot) of Springfield, O.H. 2nd Lt. Frederick V. Brossard (navigator) of Washington D.C; Staff Sgt. Arthur A. Schwartz (radio operator) of Pittsburgh, pa; Staff Sgt. Thomas L. Holstlaw (Engineer) of Iuka, IL. All of them were married and in their 20s, with the exception of the 31-year-old Holstlaw.

As reinforcement soldiers, the men would be experiencing combat for the first time. The allies massive build-up for the Normandy invasion ultimately involved 1.2 million troops – and nearly every available C-47 in British Guiana, Brazil, Ascension Island, and North Africa.

Along the way, Brossard penned a letter to his family back home, expressing a wide-eyed innocence shared by many young men of the era: “Flying high (10,000 ft.) over the white rolling carpet overhead [sic] gives one an ethereal feeling and a feeling of joyous importance in being able to do it that incomparable.”

On December 16, 1943 at 10:30pm the Skytrain departed on the final leg from Port Lyautey in French Morocco bound for RAF Station St. Eval in southwest England. The nine-and-half hour path took them mostly over open water, including the Bay of Biscay, where German aircraft frequently patrolled; as a result, Allied planes operated under strict radio silence. Prior to reaching this airspace, the C-47 was scheduled to change course at the halfway point near Cape Finisterre in northern Spain. But for reasons never fully explained, 43-30719 headed due north for Ireland and directly into the eye of a brutal winter storm.

At approximately 7:00 am on a cold, dark morning, the crew found themselves above County Kerry – home of the highest summits in the country. Lt. Schwarf presumably dropped altitude in search of recognizable landmarks, unaware that they were flying dangerously low in an area of 3,000 ft. peaks. Heading southwards direction, the C-47 slammed into a north-facing ridge. Four of the crew died instantly on impact. Staff Sgt. Schwartz, a burly 6’4” man, would be found 30 yards away from the others, suggesting he may have crawled from the burning wreckage.

Several locals recalled hearing a loud explosion that morning, but the combination of thick fog and heavy snowdrifts kept the disaster concealed for several weeks. Meanwhile, military officials in England immediately launched a rescue operation when 43-30719 failed to arrive with the other C-47s in its group. Notices were sent out to next of kin and followed by daily telegrams stating the soldiers had been listed as missing. However, on December 29, the Army officially abandoned the search, assuming the “Skytrain” had gone down somewhere in the Atlantic.

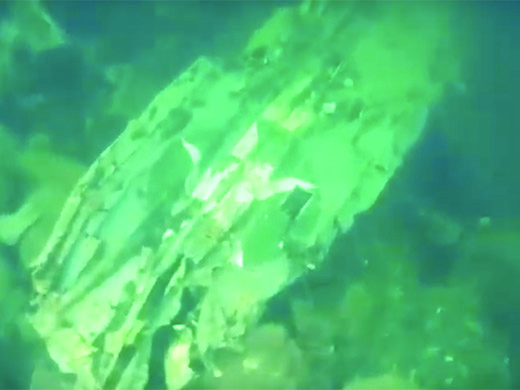

the Sky Train lies submerged in Lough Cummeenapeasta

Finally, on February 3, 1944, a local farmer named Dan O’Shea and his neighbor discovered the camouflaged wreckage while tending to sheep near Cnoc na Péiste. The discovery proved grim. O’Shea quickly notified the Gárda Síochána (local police station) in Beaufort and the next morning an Irish Army detachment arrived at the scene. Foul weather, unstable terrain, and the steep incline made the recovery of the victims extremely difficult. Among the rubble, part of a lady’s green shoe was found, bought as a present in Brazil by one of the airmen for his wife.

The deceased were coffined inside a shed in Mealis before being taken Killarney, where they received full-honor burials. In early June of 1944, around the time of D-Day, their remains were exhumed and reburied at the GI Cemetery near Belfast. Two years later, the bodies of the three officers, Schwarf, Goodin, and Brossard, were permanently interred at the U.S. Military Cemetery, Cambridge, England. At the request of their respective families, Staff Sgt. Holstlaw was reburied in Luka, Illinois, and Staff Sgt. Schwartz was reburied in Beni-Israeli Jewish Cemetery in Wilmington, North Carolina.

Over the years, both the cause of the accident and the exact date when it was first discovered had produced much debate. Various rumors asserted that witnesses heard and saw the smoldering plane shortly after impact – and that some items may have been looted. O’Shea’s son, Martin O’Shea, grew up hearing stories about the tragedy and still lives in the area. In a recent interview, he explained how poor visibility and challenging weather would have made access on the upper mountain next to impossible; additionally, loud sounds in the Reeks are fairly common as “stone ditches in these parts crashed often and made rumbling noises,” he said.

But as for how an American C-47 ended up hundreds of miles off course, several different scenarios have been examined. To date, however, no evidence indicates any human error occurred. The most likely explanation points to navigational issues such as faulty instrumentation.

In 1984, the Warplane Research Group of Ireland held a memorial ceremony to commemorate the victims and unveiled a plaque near the fatal site. A small number of the surviving relatives attended. Additionally, a separate memorial honors the victims at Cronin Yard, a campground in Mealis and the traditional starting point for ascents of Ireland’s highest peak, Carrauntoohil. A few pieces of significant wreckage can still be seen – that is, if you know where to look. A large portion of a wing that had slid down now lies permanently submerged in nearby Lough Cummeenapeasta, and one of the massive twin engines rests ominously in a rocky graveyard about a half-mile from where it initially struck the mountain.

Although the loss of life during wartime is expected and the names of those killed add to an endless scroll, Martin O’Shea wants readers to know that the young men who died in southwest Ireland on that fateful winter day “will never be forgotten.” ♦

Leave a Reply