The Visionary Behind Our Modern Towers of Babel

Few things convey a sense of progress and modernity like skyscrapers. Whether or not one finds them aesthetically appealing, such buildings dominate a city’s appearance and also let the world know that a particular city has arrived. For centuries, many an architect had wanted to build taller buildings. But not until the late 1800s did the mass production of steel facilitate the construction of tall, thin buildings that were impossible to build with previously available materials.

The man known as the “father of the skyscraper,” Louis Sullivan, was born in Boston on September 3, 1856. His mother, Adrienne List Sullivan, was a native of Switzerland. His father, Patrick Sullivan, came from an unspecified part of Ireland. This father was the only child of a widowed itinerant landscape painter who abandoned him at a county fair when he was age 12.

Louis Sullivan’s autobiography relates how his father “wandered barefoot about the countryside” with a “curious little fiddle.” Through these performances he obtained enough money for survival. Making his way to London, Patrick Sullivan focused on the art of dancing. Immigrating to the U.S. in 1847, he later established his own dancing academy in Boston.

Sullivan, the second of two children, attended Boston public schools. At age 16, he enrolled as an architecture student at MIT, but dropped out after only one year to apprentice himself to an architecture firm in Philadelphia. Several months later, he relocated to Chicago, where he worked in a separate architecture firm. In 1874 he headed to Europe and received further instruction in Paris. Returning the following year to Chicago, he worked as a draftsman for a series of firms. The big launching point in his early career came in 1879, when he joined the firm of Dankmar Adler, a German native who was 12 years older than Sullivan and already a prominent practitioner in his field.

Adler noticed Sullivan’s exceptional promise and made him a partner in the firm only two years after he joined. Soon, Sullivan was in charge of the firm’s architectural design. Adler tended to handle the interpersonal side of the business. This was a good idea: Sullivan was not an easy man to get along with. He had an abrasive tongue and scant patience for clients who wanted things rendered in a way contrary to his ideals.

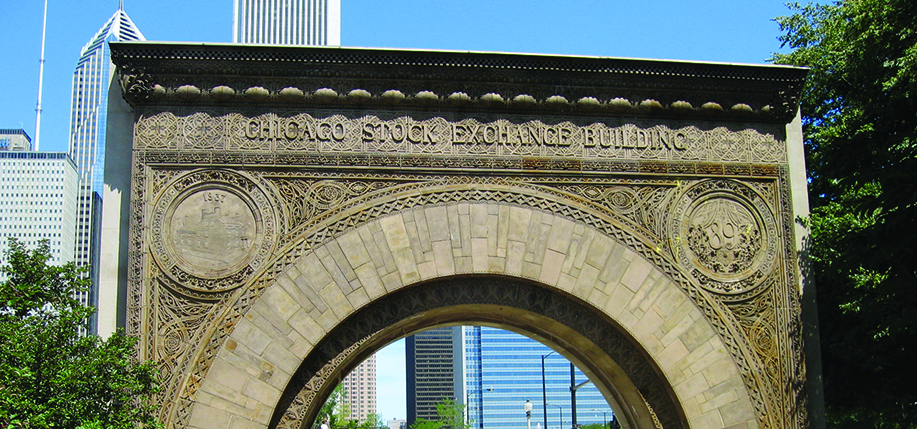

With Sullivan at the designing helm, the Adler & Sullivan firm would produce such high-profile structures as the Wainwright Building in St. Louis, Missouri; the Prudential (Guaranty) Building in Buffalo, New York; the Old Chicago Stock Exchange Building; and the Auditorium Building in Chicago, which was “the largest, tallest, heaviest, and priciest building of its era,” according to the website of the Chicago Architecture Center.

In Sullivan’s view, the new style of urban corporate building “must be every inch a proud and soaring thing, rising in sheer exultation.” Though he is often dubbed the “father of the skyscraper,” this probably gives him too much credit: There were contemporaries, and even a predecessor or two, who built similarly tall structures. And yet it was Sullivan who – through the force of his design and the apt articulation of his architectural ideas – emerged as the “father.” He had also been “the first to bring art and technology into something approaching a union,” contends Carter Wiseman in his American Heritage article “The Rise of the Skyscraper and the Fall of Louis Sullivan.”

Sullivan’s architectural philosophy was that “form follows function” – a mantra that became as sacred as scripture to many modern architects. Although Sullivan clearly sought to emphasize the functional over the aesthetic aspects of architecture, his style is somewhat difficult to categorize, as he also tended to make abundant use of decorations, including ones of a Celtic theme.

Despite being on the cutting-edge of his profession, not everything about Sullivan was so modern. When addressing his primary influences, he credited Vitruvius, a Roman architect who was born before Jesus. Of course, no architectural influence could combat the impact of the financial Panic of 1893 (an economic decline that lasted until 1897), which stultified many projects, particularly ones of a Sullivan-sized caliber. In 1895, Sullivan’s longtime collaborator, Adler, decided to leave their joint firm. This decision was one Sullivan regarded as betrayal. Adler himself regretted it and soon after tried to reestablish their partnership, but Sullivan was in no mood to entertain a reunion.

Without Adler, Sullivan did manage to obtain a few high-profile projects, such as the Bayard-Condict Building in Manhattan and the Schlesinger & Mayer department store in Chicago (now known as the Sullivan Center).

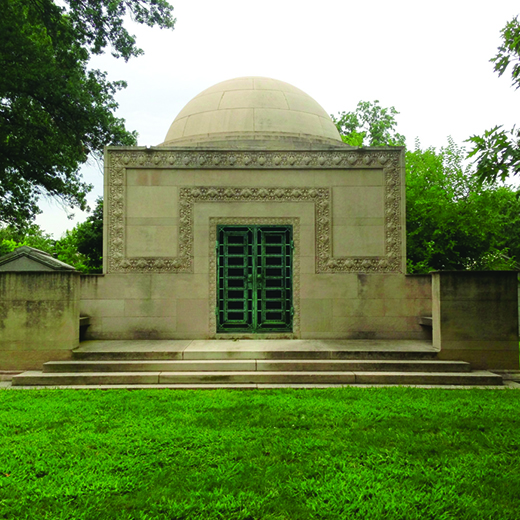

But Sullivan, regardless of his brilliance, had needed Adler’s networking and interpersonal skills in order to secure contracts for significant projects. So, instead of designing lofty buildings in Chicago and other high-profile areas, Sullivan was reduced to bidding for the opportunity to work on banks in such locations as Grinnell, Iowa; Sidney, Ohio; and Owatonna, Minnesota. Unable to cope with his skydive from greatness, Sullivan and his frayed emotions took to the bottle. Two decades of alcoholism ensued. This man had been a challenge to get along with even when his career was triumphant. After his fall from greatness, his company became all but impossible.

His wife, Margaret Davies Hattabough, whom he had married in 1899, left him in 1906. They were officially divorced about ten years later. No children emerged from their union. Mounting financial woes compelled Sullivan to sell most of his possessions. He kept downgrading offices, until he could no longer afford one at all. His living quarters were eventually reduced to a single room, subsidized by persons who pitied him. Sullivan, who had been battling kidney and heart problems, died in Chicago on April 14, 1924, at age 67.

His combativeness and self-destruction likely would have been even worse had he known that future decades would see the wrecking ball taken – often for no legitimate structural reason – to many of his buildings. Fortunately, the latter part of the 20th century saw a rising public interest in the preservation of Sullivan’s old buildings. This newfound concern largely managed to safeguard the fruits of Sullivan’s talent, along with the myriad hours provided by tradesmen and laborers who worked, almost always at dangerous heights, to fulfill his grand designs. ♦

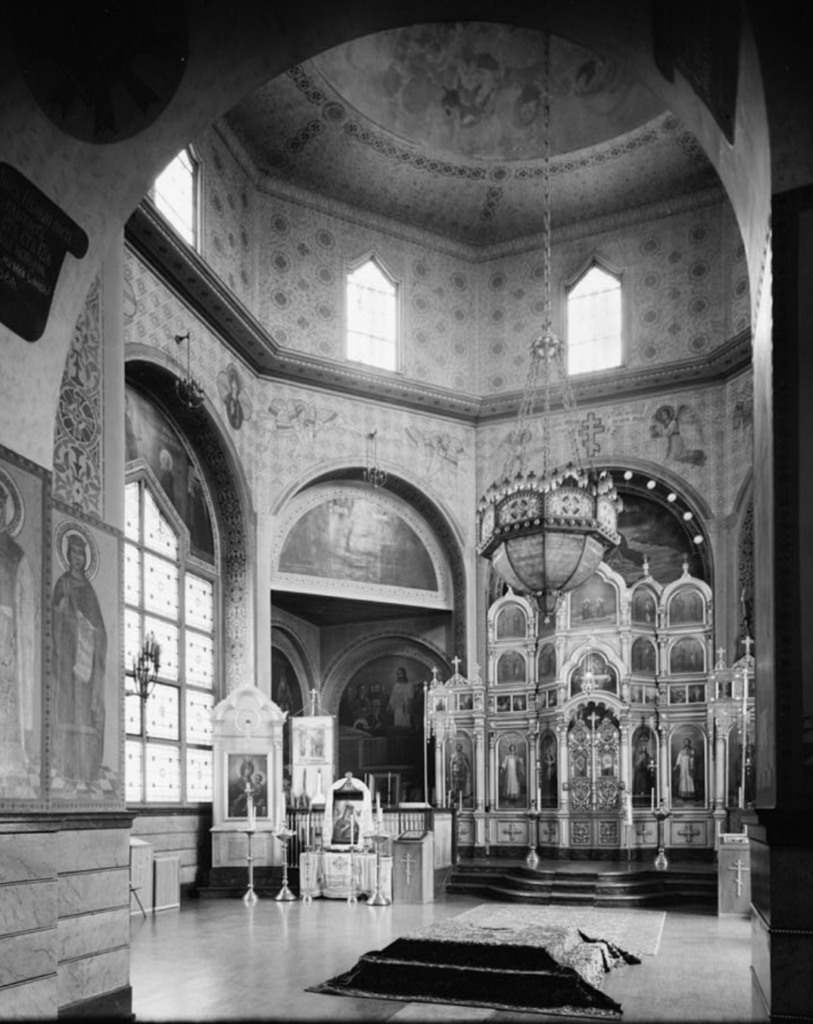

Holy Trinity was built in 1903

Frank Lloyd Wright, perhaps the greatest American architect, apprenticed with Sullivan. FLW was not the skyscraper type however.

Excellent articles. There was a program on television many many years ago on architecture which referenced the beautiful designs of Louis Sullivan and Francis Lloyd Wright comparing them with the cement boxes being built later.

Regards, Harry Dunleavy