Paul Boskind, Ph.D. is a psychologist, chief executive officer, National LGBTQ activist, philanthropist, and Tony Award-winning producer and owner of a castle in Ireland.

Paul Boskind couldn’t have picked a better time to visit Ireland. As he checked into the Fitzwilliam Hotel, the desk clerk warned, “It’s going to be crazy here tomorrow. It’s the parade.” It was June 23, 2017, just ten days after Ireland had elected one of the world’s first openly gay leaders, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar. The parade was Dublin’s 15th annual Pride Parade, and for Boskind, an LBGTQ activist, it was significant. Paul already knew Ireland had been the first country in the world to approve same-sex marriage by popular vote, so when he heard Varadkar speak to the group, he was inspired. This day came not long after he discovered, much to his surprise, that he was mostly Irish. “I found out through the 23&Me genetic testing,” he explains, adding he grew up not knowing anything about his O’Shea ancestors, who, generations earlier, had emigrated from Cork. And, he admits, he didn’t know a whole pile about Ireland, either.

Ireland did not disappoint on that first trip and has not disappointed since. “I found the Irish to be a generous, convivial people and was impressed by the country and the countryside. I looked at castles, stayed in castles, then, in that same trip, bought a castle – that’s how I operate.” I realized, over three interviews, that Paul makes fast decisions, always going with his gut. But still I felt something greater pushing him, a sense he’s racing against time. He is; his eyesight diminishes daily.

He lives in a penthouse in New York’s theatre district, where, over lunch, he told me about his childhood, growing up in San Antonio. His family had four children and no money, so young Paul would sell papers door-to-door, making about a three-dollar profit. He used the money to buy a Christmas present for his mother, “maybe a drugstore hand cream.” His father fixed things up, including cars, and sold them. “To get to school on time, we would get up early and spend time cajoling an old car to move.”

Paul remembers saying to his parents, “I’m hungry,” only to be told to eat some cornflakes. His father had brought home a crate of cornflakes that he’d gotten cheap because a forklift had sliced through the container. “For months on end, we had corn flakes for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.”

There wasn’t a whole lot of money for luxuries for Paul and his two older sisters and a younger brother, but his mother made him take piano lessons. Today, in the corner of his living room, a grand piano is thrown into relief against the modernist décor and 360-degree view of Manhattan’s skyline. He doesn’t play anymore, but the piano, graced by a photograph of Annie Lennox, still gets plenty of use.

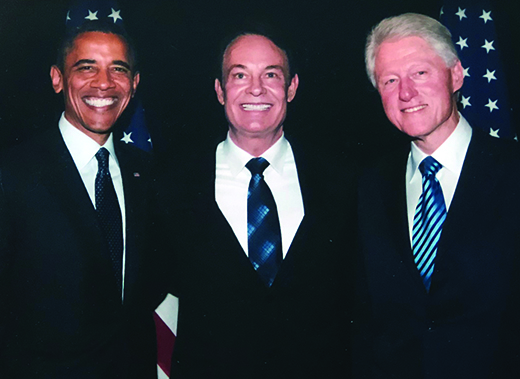

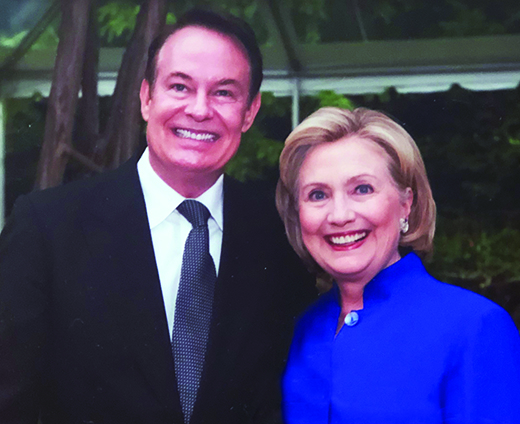

Today, Paul is an activist, who’s hosted numerous Democratic fundraisers for presidential, senatorial, and congressional candidates. He’s on the Democratic National Committee (DNC) finance committee and also serves as national co-chair on its LGBTQ council. He’s committed to raising funds for the DNC, but is no easy mark. “When candidates come to raise money in New York City – and they all do – they come knocking on my door, I open it, have them sit with me here on this couch and don’t hold back in vetting them.”

He doesn’t hold back with advice either. “[Presidential candidate] Pete Buttigieg was talking to me about his religious faith and I said you’ve got to be careful with that. I reminded him that twenty-three percent of Americans are non-believers.” Buttigieg listened. “At the LGBTQ Victory Institute when we endorsed him as a presidential candidate, he told me, ‘Paul, I’m coachable,’ which I found so pleasing and impressive.”

Youth

Paul grew up a Seventh-Day Adventist schooled in the Scriptures and the Second Coming of Christ, but his family left the church when they discovered the minister was having an affair with a member of the congregation. Paul, at first, was happy. “Saturday, the cartoons came on television, and finally I could watch because I didn’t have Sabbath school.” But as he entered adolescence, he was looking for guidance. The guys in his neighborhood were changing. “They had started using marijuana and drinking beer. I was like, ‘I don’t want to do that.” He looked for something different: “I was 16, had my driver’s license, and was independent; I visited about ten or twelve different churches until I found a Lutheran church I liked.” A born leader, Paul became the president of the Youth Action Ministry and managed to convince the pot-smoking, beer-drinking kids to join the congregation.

In adulthood, his zeal turned into profound disillusion: Paul’s journey from religious ministry to non-believer is rooted in his anger at the Christian right’s rhetoric that seeks to demonize gay people.

“They say gays are going to destroy the family, and all kinds of other, nasty stuff. And when we got marriage equality in the United States, the evangelicals moved abroad and they’re doing the same hateful things they did here.” He mentions the American evangelical support of Vladimir Putin, a despot they nonetheless view as a guardian of traditional values. “This is, in part, why I have become so anti-religion, and frankly, I’m an atheist. I think the whole biblical god stuff is nonsense. And so I’m into that group of the twenty-three percent of Americans who consider themselves non-believers,” he says.

To earn money for college, he sold bibles door-to-door in Virginia and North Carolina, and once, over a long weekend, he made a trek up to New York City that would stay with him forever. “It was thrilling. I was, like – ‘Wow! Look at all these skyscrapers.’” He also remembers not being able to afford a Broadway ticket, but still, the seed was planted – he returned to Broadway as an award-winning producer.

With his bible money, Paul moved out of the dorm and bought a mobile home. He changed universities and then enrolled at the University of Texas at San Antonio, but found he couldn’t focus. “I changed my major seven times. I would enroll and then dis-enroll. I was averaging a 2.0, and I wasn’t even sure I would finish the semester.”

Then a day came when he couldn’t see a protozoa in a lab microscope. He’d worn glasses since the sixth grade, but this was different. He hoped there was something wrong with the microscope, but when he still couldn’t see through another one, he realized that it was his eyes. What followed were many trips to his local medical school looking for an answer. “I probably had twenty student physicians looking in my eyes and asking questions.” Worse, the doctor who would give him the grim diagnosis had an obscene bedside manner.

“I was all alone in a room and he came in, all pleased with himself, ‘We know what it is.’” The doctor remained smug, “It’s Stargardt’s disease. You are going to go blind.’” Paul couldn’t believe it, “You mean like pitch-black dark blind? When is this going to happen?” In an attempt at black humor, the doctor said, “You’ll be the first to know.”

Paul had arranged to meet his mother after the appointment. She’d been picked for a dance review and had co-opted Paul to be her partner. “It was a rehearsal and as we danced around, she asked me how the appointment went.” Mid-dance, he answered, “The ophthalmologist told me I’m going to go blind.”

After the initial shock Paul says it focused his attention on the future. The diagnosis put him on the fast track, “I had this, I-got-to-do-this-before-I-go-blind kind of mentality.” After nearly flunking out of college, he turned it around. “I got 30 hours of credits in one semester. I’d grab a marketing book and read it over one weekend and then take the Advanced Placement test and get credits for courses,” he recalls. He graduated and was accepted into grad school at Hofstra for a doctorate in clinical and counseling psychology. Hofstra, in Hempstead, Long Island, had much to offer the kid from Texas, but its biggest attraction was the short commute to midtown Manhattan and the theatre. He took in as much of New York as time and money would allow, but after getting his degree as a psychologist, he moved home to Texas. “I probably moved back too soon, but my sister was pulling for me to come back home,” he says now.

After working for a large medical practice with a behavioral health specialty, he decided to go into private practice and made a go of it right away. “I’m a really good clinician,” he explains, crediting his success to a results-oriented mentality. He’s not the kind of therapist who wants to see his patients return year after year. “I put a lot of pressure on the patient to get better,” Paul explains, “I don’t ever want to be working harder than my patient. From the beginning, I make sure we are very clear about what we’re working on, what our goals are, and what the prognosis is.”

Clinical Psychologist

He established clear standards for his practice: everyone, whether the physician or the pediatrician or the neurologist or the counselor or the schoolteacher, must communicate with each other, so that the patient is getting a clear directive on moving forward. Word of mouth about his work, especially with children and adolescents, spread, and his company was awarded a contract with child protective services to treat abused and neglected children. “The goal was integrating kids back into the family, but only if the parents or caregivers could prove they could be responsible. With contract in hand, he opened up five new locations in South Texas, and soon had 23 outpatient locations throughout Texas.

Expansion Into Nursing Homes

A drive-by shooting opened a window onto another group who were in serious need of mental and behavioral therapy. At the request of a friend, a physician, Paul made a visit to see a patient at a nearby hospital. His caseload was full, and he didn’t want to take on any more patients, but he changed his mind when he met the victim of the shooting, who was now paraplegic. The doctor who contacted Paul was enraged – the psychiatrist who had seen the patient wrote a prescription for Prozac and walked away. Paul remembered, “He was lying on his back, with tears rolling down his face. I knew this guy needed therapy, so I stepped in.

My doctoral dissertation is on adjustment to physical disability with a specialty in blindness. I was like, ‘We’re going to get him into another room, and get his bed next to the window. Let him look up at the clouds and the blue skies.’ In time, he went into a nursing home, where I continued therapy. A nurse approached me and asked, ‘Help me understand this. You’re a psychologist?’ I said yes, explaining I had seen the patient at the hospital and I was checking to make sure he was adjusting well. She said, ‘So basically, you’re making a house call.’ And I said, ‘Well, I guess you could look at it that way.’ She answered, ‘Okay, then I’ve got some more patients I’d like you to see.’ Back in my office, I asked the staff who would be interested in working with the geriatric and disabled population – so many jumped in, ‘Yes!’ And that’s how we started providing psychological services in nursing homes, all from that one paraplegic patient. Now we have nearly 700 employees, and we’re providing services in thirty states around the country and growing.”

Campaign for Equal Rights

As his business was growing, Paul was also changing. During college, he was engaged, but before the wedding he broke it off, admitting to his girlfriend that he was gay. In embracing his own homosexuality, he was keenly aware of the challenges facing others. And Texas being second to California in states with the most total active duty and reserve members of the military, Paul was drawn to the campaign to repeal, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” The official U.S. policy on gays serving in the military service had been instituted by the Clinton administration on February 28, 1994. The law discriminated against openly gay and lesbian individuals serving in the armed forces, and for 17 years, the Human Rights Campaign fought to change it. Paul was there on September 20, 2011, when President Obama certified the repeal. It was a high point in his life, and it served as a stepping stone to further activism.

Continued Activism

“I was on the national board for Servicemembers Legal Defense Network and then also joined the board of directors of the Human Rights Campaign and then that progressed to involvement with the global arena,” Paul says. He also joined the National Democratic Institute (NDI), a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization working to support and strengthen democratic institutions worldwide, and co-founded, under the NDI umbrella, Equal Voices for Democracy, which is an initiative that expands LGBTQ participation in political life.

This past October he was in Tunis, Tunisia, for an NDI Board meeting where he met the president of Tunisia. “I had an opportunity to meet with some LGBTQ leaders in that country where it is criminalized to be homosexual.” He has also traveled with Equal Voices to Columbia, Ukraine, and Georgia. And here in the U.S., he has consistently served as a crucial bridge and unifying voice between LGBTQ organizations and helped coalesce organizations such as Equality Texas, the Tyler Clementi Foundation, HRC, and the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network (SLDN). And, though his board membership with the NDI, Paul is at the frontline of political movements.

Broadway Calling

In 2007, Paul upset the religious right when he produced Southern Baptist Sissies at the Church Theater in San Antonio, which he owned and operated. The play, by Del Shores, is about four gay young men who have grown up in the Baptist church, loving Jesus and the community of the church but finding themselves at odds with it. The play was a huge success in spite of – or perhaps because of – the protest lobbied against it by the evangelicals. Paul realized that theater could be used to educate audiences to pro-equality issues and entertain people at the same time. He turned his attention to Broadway, and from not being able to afford a ticket on his first visit to New York, he went on to producing a string of successful gay-themed plays.

His Broadway credits include highly acclaimed runs of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (2011), The Best Man (2012), and Mother and Sons (2014). He won the Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play for the 2011 Broadway debut of The Normal Heart. The groundbreaking drama showcased the tribulations of the early 1980s AIDS crisis in New York City.

Sláinte

While he still keeps a home in San Antonio, Paul’s main residence is in New York City, where he navigates easily around his neighborhood. He grabs his “blind-boy cane,” and we walk the three blocks to his favorite neighborhood restaurant, where everyone knows his name and his food preferences.

His eyes miraculously held out against the encroaching blindness for years. It’s only recently – in the past few years – that his vision has deteriorated. He still has enough sight to clink my glass in a “Sláinte.” I ask him about that and he says, “it’s because I can see the red of the wine held up against your white shirt.” We are drinking a Malbec, an inky dark red. It’s his favorite wine, and it’s the blend that his winery in Argentina makes. Here, too, the bottle carries a message. The wine label reads “Igualdad,” which is Spanish for Equality.

It’s easy to forget that Paul is visually impaired – he moves with grace and is fast on his feet. Stargardt’s robs the central vision of the eyes, leaving the peripheral vision. When he’s checking someone or something out, he turns his head to the side to see. He’s in a support group of other visually impaired adults, which includes an Irish woman, Fiona, who is a good friend. He often leads the support group by placing a box of tissues on the table. “It’s okay to cry,” he tells new members.

I ask him what he misses most, and he says theatre. He used to manage well enough sitting a row or two from the stage, but now that’s not enough. Sad for a beat, he brightens up when he tells me how My Fair Lady provided audio description for patrons who are blind or low-vision, with prompts such as “Now Eliza’s moving towards the center of the stage.”

“It was so wonderful. I cried. Tears literally ran down my face,” he tells me. Hopefully audio descriptions will become a theater norm.

Clonbrock Castle

Paul is not one to dwell on stuff that can’t be helped. His life is full, and when talk turns again to the castle, he’s especially animated, discussing the renovation he’s carrying out on the 15th-century Clonbrock Castle, which was on the market on that first trip to Ireland in 2017. He finalized purchase in February 2018. Located in Ahascragh, a village in rural Galway near the town of Ballinasloe, and situated on a tributary of the River Bunowen, the property also has a 18th-century gardener’s house, and two other one-bedroom cottages, where he stays on his monthly visits to oversee his renovations. Paul has high praise for his contractors, but he’s actively involved. “We’re getting close to finalizing the tower house and I’ve already had the furniture delivered.

I ask, “What’s your long-term plan for the castle?” Paul answers, “It’s my residence.” He’s even looking forward to the damp Irish winters – a fire in the grate, a good glass of wine, and good company.

Paul brings to mind another castle owner: William Bui (“golden haired”) O’Ceallaig (O’Kelly). During Christmastime 1351, O’Kelly sent invitations – the opening words, “Like the surge of the stream is my welcome to you” – to all the poets, storytellers, musicians, and entertainers across Ireland. They were to come to a feast at his castle. What happened next was the one of the greatest parties in recorded history, lasting well over a month. Later, the O’Kellys were forced out of Ireland, and they joined the legendary Wild Geese who fought and served with honor around the world.

The chieftain now in residence at Clonbrock Castle shares O’Kelly’s activism in political issues supporting global human rights. He’s also a patron of the arts and while we’re not expecting Paul Boskind to invite every poet in Ireland to a month-long feast in his castle (or are we?), there’s sure to be good times ahead, good parties to look forward to, and some great discussions. Sign me up! ♦

Intriguing story. Good presentation

Hi, Patricia & Mary: Thank you for that beautiful & moving story on Paul Boskind. Ahaskragh of the Castle, & also of two of our great musical talents, the late Seán ‘ac Donncha and Máirtín Byrnes, both of whom I featured on my RTÉ radio programmes. Máirtín I first met at Hon. Gareth Brown’s house where he supplied music for dancing for a small group of us that included the late Eddie Delaney, sculptor, & movie actor, John Hurt. Paul would have loved it.

Paul sold papers not peppers typo in your article, Paragraph 3.

Loved the story very interesting about an old high school friend.

HiSusan!! Maybe Paul will give me a discount on his mental health services!????

Bravo. A robust story about an impressive man.

Wow congratulations you are flying high !!! Its really impressive Paul. And doing everything and more you said you would.

Slight correction, the castle grounds lay between two parishes with the Bumowen River splitting both, some of the lands rest on the Ahascragh side but the Tower, House and buildings rest on the Fohenagh side

Nice job. Congratulations to the same Paul Boskind I worked for at Deer Oaks. You’ve come a long way from where you began.