A new National Library of Ireland exhibition celebrating the life and work of Seamus Heaney gives an overview of the poet laureate’s life and work.

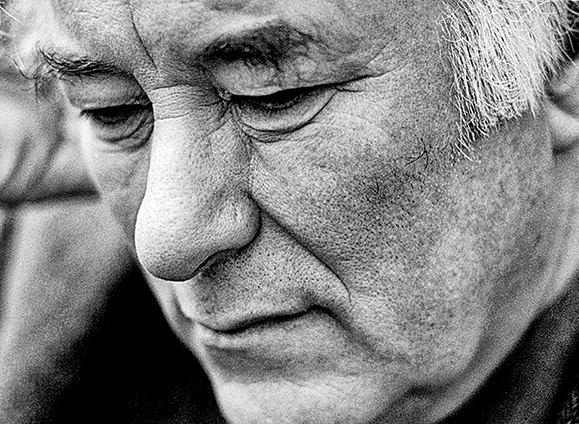

When Seamus Heaney was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, the Swedish Academy noted the “lyrical beauty and ethical depth” of his work. His poems, though often suffused with allusions to Dante, Homer, and the other greats, are written with startling directness and offer intimate portraits of his life: his mother’s head “bent towards my head,” as they peel potatoes “While All The Others Were Away At Mass,” or his father crying at the funeral of his younger brother in “Mid-Term Break.” Heaney, himself, died unexpectedly at just 74, in 2013, but the intimacies that defined the man and his work are not lost. Two years before he passed Heaney donated his archives, some 10,000 pieces of paper, to the National Library of Ireland “carrying in the boxes himself,” his son Mick recalled. And that archieve is now central to an exhibition that offers an overview of the Nobel laureate’s life and work. Titled “Seamus Heaney – Listen Now Again,” the exhibit, at the new cultural space in the grand 18th-century Bank of Ireland building in Dublin, explores the poet’s early life on a farm in Derry, his first creative success, the impact of what he called the “life waste and spirit waste” of the violence that surrounded him and his endurance as a poet and public figure.

Curated by Geraldine Higgins, director of Irish Studies at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, the exhibit is a kind of labyrinth, shaped like one of Heaney’s poems, weaving past a digging spade, pens, envelopes, notebooks, letters, and the actual first drafts of a number of his poems. There is even a pile of dark brown turf – burned to provide warmth but also a densely layered source of creative inspiration. The title of the exhibition, “Listen Now Again,” is derived from his 1996 poem “The Rain Stick.” An actual rain stick, a dried and hollow cactus stalk with small, hard seeds inside, is featured in the exhibit. Upend the rain stick, as the poem asks you to do, and take in what you hear. Heaney heard a “music that you never would have known to listen for.” “Downpour, sluice-rush, spillage and backwash

Come flowing through. You stand there like a pipe Being played by water,”

Turn it over again, even “a thousand times” writes Heaney, and the wonder is undiminished. Does it matter where the music comes from, Heaney asks, even if it’s simply the “fall of grit or dry seeds through a cactus?” To enrich your life, “Listen now again.” Heaney described the poem to fellow poet Dennis O’Driscoll in the book of interviews Stepping Stones, as capturing his middle-aged desire to “keep the lyric faith,” by being open to moments of being “irrigated by delicious sound.” That faith in the power of his unique poetic voice began early. He was keenly attuned to the feel, smell, and sounds of the rural world around him – the thatched cottage where he grew up, and the pastoral countryside. “Digging,” from his first published book of poems when he was 27 years old, is featured at the entrance to the exhibit. The poem describes his father and grandfather, bent low digging among the flowerbeds and potato drills. They dig “down and down,” for the quality turf, which makes a “squelch and slap” as the turf spade is plunged into the soggy ground. But the poet can’t follow “men like them.” He finds other ways to work developing his creative life.

“Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests. I’ll dig with it.”

The early poems are full of sensual images of nature, household, and fieldwork. There are dunghills, gross-bellied frogs, cow’s milk, black berries like “thickened wine,” and on churning day “gold flecks” of butter that “dance” in their crocks. For Harvard professor, critic and friend of Heaney’s Helen Vendler, the early works are poems of “agriculturally tamed nature,” “beauties of arrangement” that Heaney would develop in his poetry and prose. Heaney described men and women working with their tools: spades, barrows, pitchforks, divining rods. Arms ached, hands blistered, and muscles toughened. What rescues the early poems from rustic sentimentality, writes Irish journalist Fintan O’Toole, are undercurrents of sex and violence and “a tang of sweat and the ache of toil.” “Listen Now Again” grants a good deal of space to the pervasive death of Northern Ireland’s “Troubles.” Heaney grew up in a Catholic household in County Derry, at a time when Catholics were marganilized. Violence exploded there in 1968, with thousands killed over the next several decades before a peace process initiated in the mid 1990s resulted in the Good Friday peace agreement of 1998, brought the worst of the bloodshed to an end.

The “Troubles,” according to Vendler, “entered the poet’s domain with such suddenness.” There are copies of newspapers announcing the death of Irish Republican Army (IRA) hunger striker Bobby Sands and pictures of British check points and bombed-out shops. A striking picture of a mummified corpse, still embedded in dirt, visually introduces one of the central metaphors Heaney used to explore what he saw as the “archetypal pattern” of violence that was afflicting Northern Ireland.

Heaney had read a book by P.V. Glob on The Bog People, a study of Iron Age bodies discovered in Denmark. Glob surmised that many of the dead were victims of ritual sacrifice to a fertility goddess to ensure the next season’s crops. In a series of poems in Wintering Out, published in 1972, and his 1975 book North, Heaney uses the stark imagery and sacrificial theme of the bog bodies to reflect on what seemed to be a primal urge towards violence and vengeance in Northern Ireland. The years between 1972 and 1975 were some of the worst of the conflict. Heaney presses together images of death, beauty and terror in poems that evoke the bog as a “memory bank” of personal and historical consciousness.

The “Grauballe Man” from his book North, seems to weep,’

“The head lifts,

the chin is a visor

raised above the vent

of his slashed throat.”

He is “perfected in memory,” “hung in the scales with beauty and atrocity:” before, in the final stanza the hard facts, “the actual weight of each hooded victim, slashed and dumped” jolts the reader out of the past into the present. In the sectarian bloodletting in Northern Ireland, “enemies” were often hooded, interrogated, and then shot. Irish literary critic Declan Kiberd wrote that Heaney risked sanitizing and prettifying violence through aesthetic distancing in the bog poems, also pointing out that “archetypes” are not subject to real changes that politics and social movements can bring. What saves the poems from historical evasion is Heaney’s own self-critical wisdom. Writing, Kiberd concludes, was Heaney’s alternative to violence, “his way of taking power.” There are moments, as Heaney clearly knew, when hope and history could indeed rhyme.

In 1972, Heaney and his wife, Marie Devlin, moved their family out of Northern Ireland to a cottage he referred to as his “listening post” in Wicklow, just south of Dublin. Heaney said the move was not politically motivated but driven by an “inner necessity as a writer.” His own reflections didn’t stop some journalists and activists from branding his relocation a “betrayal.” In the poem “Exposure,” the final poem in North, he describes himself as having “Escaped from the massacre,” an “inner émigré, grown long-haired and thoughtful;” and adopting a “protective colouring” at his poet’s desk in the countryside. From another poem in the same volume he is the Irish Hamlet, “dithering,” “blathering,” and “jumping in graves” at a safe distance from the fight. Ever since achieving notoriety as a poet and writer, Heaney had been pressured to make statements for the Catholic and nationalist struggle in Northern Ireland. Political partisans demanded to know “what the bog had to do with the Bogside,” Heaney quipped, a reference to the Catholic working-class area of Derry and stronghold of the I.R.A.

In his 1995 Nobel speech, he outlined what he saw as his complex dual role – being “true to the impact of external reality and …sensitive to the inner laws of the poet’s being.” And in his essay “Frontiers of Writing,” part of a lecture series he delivered while teaching at Oxford University, he reflected upon his “need to be true to the negative nature of the evidence and at the same time show an affirming flame, the need to be both socially responsible and creatively free.” Stamina is a theme that recurs in Heaney’s poetry and life. In the poem “Keeping Going,” Heaney praises his brother Hugh, who stayed to work the family farm, as having “good stamina,” as he does his daily work amidst the bloodshed that stains newly painted white walls.

“You stay on where it happens,” Heaney writes.“Your big tractor

Pulls up at the Diamond, you wave at people,

You shout and laugh above the revs, you keep

Old roads open by driving on new ones.”

While Hugh cannot “make the dead walk or right wrong,” he keeps going. Heaney understands that violence and death cannot be whitewashed away, but that endurance and hope is a kind of heroism amidst the killing. It is the same commitment that sustains the initial excitement that revs up a poem, through to a successful composition. “Listen Now Again” makes clear that Heaney was worried about and worried over words. Numerous typed and written worksheets for poems show edits and changes in word choice as he digs down for the right image or “musically satisfying order of sounds.”

Heaney warned against a binary language, the “Irish-English antithesis, the Celtic-Saxon duality,” that locked minds and spirits into predictable and dreary patterns. He was always divining, trawling, and letting down shafts in search of “unnamable energies” that fueled his poetry. If people were more attuned to the complex language of poetry they could be inoculated against the flimsy and now pervasive filthy rhetoric of hollow politicians.

You might say that some of Heaney’s non-binary language made it into the 1998 Good Friday peace agreement that recognized the right of the people of Northern Ireland to identify themselves as “Irish or British, or both…” This is a fluid language with verbal nuances that might prefigure an alternative political imagination.

As you exit the exhibit there is a small room with Heaney’s last words “Don’t Be Afraid,” printed in large block letters on a slate wall. He had texted the touching words – in Latin – to his wife Marie shortly before he died. Visitors can write their own messages – or poetry – on the wall.

Sophie Doyle, who is part of the educational team that gives public tours of the exhibit twice a week during the summer, says that over 110,000 people have visited the installation since it opened a year ago. In 2011, Heaney himself brought boxes of material to the National Library, where his papers are permanently placed and open to the public and scholars.

“There is a competition over who is Ireland’s most loved poet, Yeats or Heaney,” Doyle said. “We are an art- and culture-based society,” Doyle added, “and so many people feel a deep connection with Heaney because he was so available, did so many readings and book signings, and was in the public eye.” Doyle points out that towards the end of his life Heaney’s poetry became more personal, dealing with family, friends and newborn grandchildren. Heaney described it as making space “for the marvelous as well as the murderous.” In his last book of poetry The Human Chain, in the title poem Heaney evokes imagery of working in solidarity with others “hand to hand,” and “eye to eye” as he helps with the task of lifting bags of food meant for the needy onto a trailer. There is an “unburdening” after the “next lift” and a “letting go which will not come again.

Or it will, once. And for all.” “Seamus Heaney: Listen Now Again” is open Monday through Saturday 10 AM to 4 PM at the Bank of Ireland Cultural and Heritage Center, Westmoreland Street, Dublin 2. It will run until the end of 2021. ♦

Well, well, the ladies like Seamus Heaney in what has become the Irish American Woman Magazine.

That laughable comparison of Heaney to Hamlet, showing such a non-comprehension of the Prince – as an idiot. If Heaney is one he need not try to claim Hamlet as his twin.

” In 2011, Heaney himself brought boxes of material to the National Library,” Ha. Shakespeare certainly never did such a thing. He made no effort to preserve his work or get credit for it. It is immortal. How soon would Seamus’ be forgotten if he had not carried it in and nailed it down like this?

Who says he and Yeats are in competition for our best? The statement is ludicrous. Heaney has a little talent but they are realms apart in achievement. There are so many others ahead of him, Swift, Sheridan, Thomas Moore, Joyce…

Enjoy your day ladies.

Seamus Heaney may be your pet with his depiction of men, like Jesus, sacrificed bloodily to the fertility Mom but time will tell.

“You can fool some of the Irish people all of the time…”

Pat

Moving review. I’m on my way for a visit next time I’m in Dublin.

Thanks,

El