Calgary, nicknamed “Cowtown,” is home to the largest rodeo in the world, the Calgary Stampede, which annually draws millions of visitors. The first Calgary rodeo in 1912 was organized by a New Yorker with Irish roots, as Ray Cavanaugh explains.

Cowboys seem like a self-assured lot. But Guy Weadick was more than self-assured; he was a bold visionary, and the fulfillment of his vision would produce an iconic western event that endures to this day.

However, this legendary cowboy actually came from the “Irish side” of Rochester, New York, where his life began on February 23, 1885. He was the oldest of five children born to Mary Ann Weadick, née Daniels, who is described by the Calgary Herald newspaper as an “Irish-Canadian woman.” Further details on her Irish roots have proven difficult to obtain.

Weadick’s father, George Weadick, was an American-born railway worker. According to the available records on findagrave.com, the father’s parents (James and Ann Weadick) were both immigrants from Ireland. Though their county of origin is not mentioned, a search on the genealogy website WikiTree.com shows that the Weadick name has a pronounced link to County Wexford.

As a youth in Rochester, Guy Weadick was enchanted by tales of the Wild West. This enchantment quickened with each new letter his family received from a relative who had made the journey. So, at age 17, he headed west on his own.

Weadick began working on ranches. “He was really interested in the authentic stories of the Old West,” related Donna Livingstone, author of The Cowboy Spirit: Guy Weadick and the Calgary Stampede. Livingstone suspects, though, that Weadick was a less-than-ideal cowboy because he “talked too much.” But she also related that he was a good listener who devoured veteran cowboy accounts pertaining to the bygone golden age of the frontier.

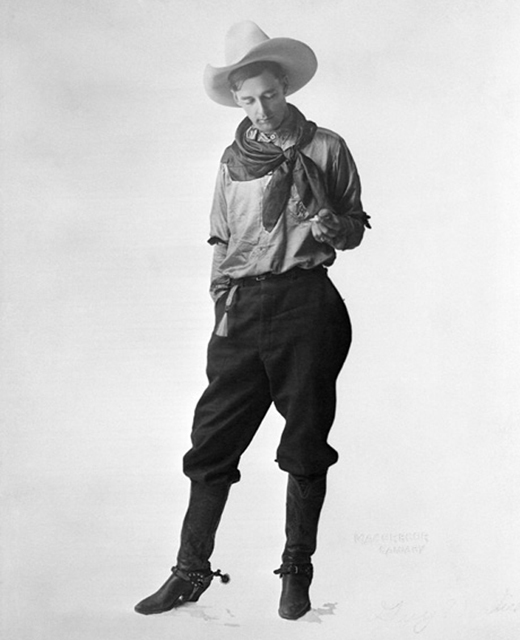

Along with listening well, Weadick became adept at riding and roping. With these skills, he made the switch from ranch hand to performance artist and began roping cattle on the Vaudeville circuit. This type of job environment was better-suited to his showman tendencies and talkative nature. He also learned how to put together an entertaining and profitable event.

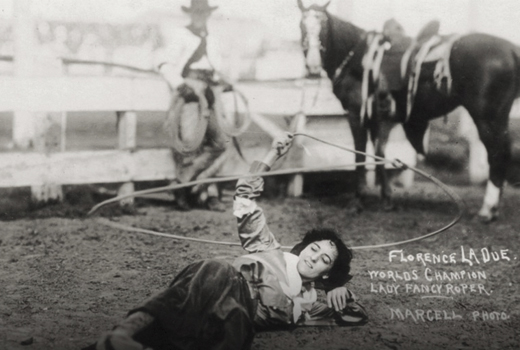

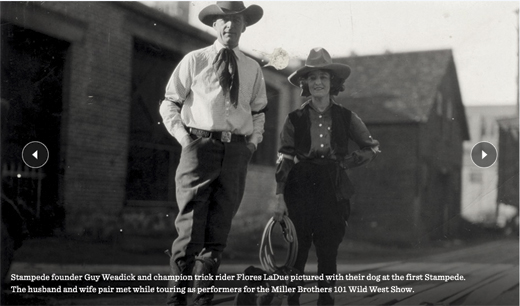

In 1906, Weadick met Grace Maud Bensel, a trick roper better known by her stage name Flores LaDue. After a five-week courtship, they married, and stayed together until her death in 1951. They often performed together at many venues on both sides of the Atlantic.

While visiting Calgary in 1908, Weadick felt that the young city – which had been incorporated just 14 years beforehand – was “on the brink of modernity but still firmly rooted in its Old West origins,” according to the website of the Calgary Stampede (calgarystampede.com).

He believed that the city was an appropriate venue for his plan: a Wild West show…not some parody exhibition either, but the real thing. There would be a huge parade, along with competitions for calf-roping, bareback bronco riding, steer decorating, steer wrestling, and other items in the cowpuncher skill-set.

The ambitious dreamer pitched his idea to H.C. McMullen, a livestock agent for the Canadian Pacific Railway. McMullen was intrigued, but said that he didn’t feel the idea was viable at that time. Four years later, in 1912, he sent Weadick – then performing in Europe – a letter saying that the time was right.

Weadick headed to Calgary. Once he arrived, though, his attempts to obtain sponsorship were unsuccessful. Things reached a point where, despite his self-confidence and panache, he was on the verge of giving up. But enough moxie remained for him to meet with a group of ranching moguls, known as the Big Four. These wealthy men agreed to provide the necessary financial backing on the condition that Weadick would make this event the “greatest thing of its kind in the world.”

The Rochester-born cowboy promised to oblige them. But he needed to christen the event with a name that would encompass the grandeur and energy of what he envisioned.

“Stampede” was the chosen appellation. What could be more exciting than a stampede? No other cowboy promoter had dared to call his event a “stampede.” And the name was certainly catchier than something like “Wild West show.”

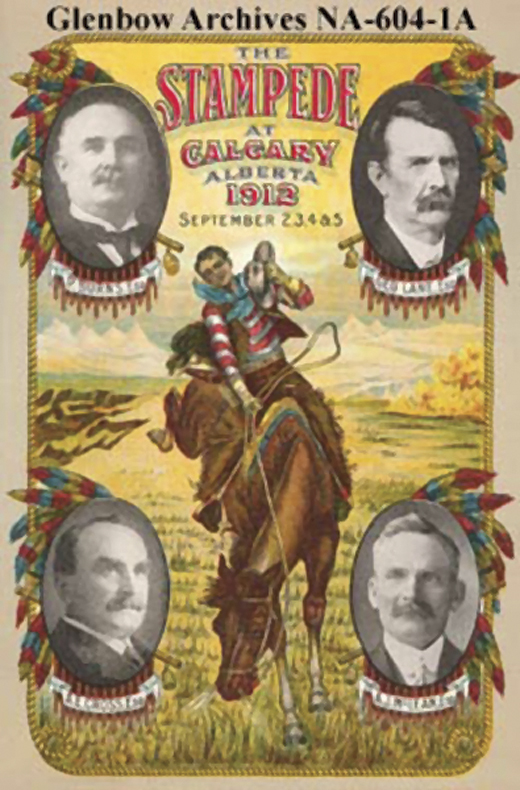

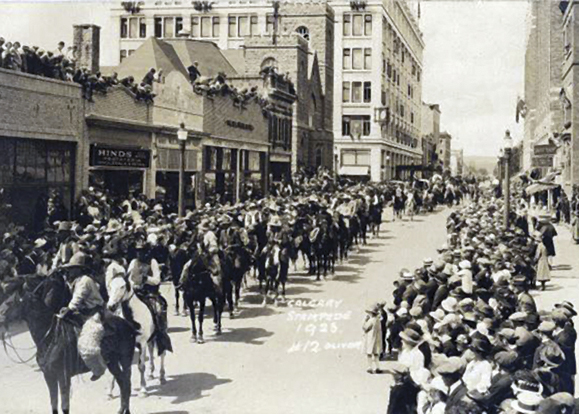

The inaugural Calgary Stampede took place during September 2-7, 1912. Trains full of spectators swarmed the city, and an unprecedented amount of prize money promised for competition winners enticed cowboys from the furthest frontier horizon.

Weadick also decided to involve the region’s indigenous community. Such inclusion of native peoples had an added significance at that time: owing to the laws of the Indian Act, natives were prohibited from holding cultural celebrations, even on their own reserves. However, the persuasive Weadick coaxed the Canadian government into allowing indigenous persons to celebrate their culture at the Stampede.

The extravaganza did have its complications, including bad weather. Many activities were postponed, and there was a pervading sense of disorganization. But the wildly authentic and effectively promoted Stampede proved to be the most-attended event in Calgary’s history. Some 80,000 persons came – a number significantly higher than Calgary’s population at the time.

Though the 1912 Stampede generated good profits and great notoriety, most people – including the sponsors – viewed it as a one-time event. But Weadick, ever the promoter, wanted to do it again the following year. So he moved the event to Winnipeg in 1913, but the result was less than successful. Six years later, in 1919, Weadick returned to Calgary for the “Great Victory Stampede,” which, aside from its western focus, celebrated the homecoming of WWI veterans.

The Stampede became an annual event in 1923, upon merging with the Calgary Industrial Exhibition. Several consecutive years of excitement and prosperity would follow. By the early 1930s, however, there was trouble: the far-ranging impact of the Great Depression had led to declining attendance and monetary losses for Stampede stakeholders.

Another serious issue was that Weadick felt the Stampede’s board of directors had become too controlling. As he was rarely one to keep quiet, arguments ensued. Soon enough, the directors decided that Weadick had already served his purpose, and now had to go.

Suing for unfair dismissal, Weadick won his court case but received only moderate financial compensation. Holding a grudge for decades, he did not return to the Stampede until 1952, when he was received as a guest of honor. A little more than a year later, on December 13, 1953, he died at age 68.

Weadick’s biographer Donna Livingstone described him as a “relentless” optimist and salesman whose launching of the Stampede marked “a turning point in Calgary’s development.”

The Stampede, now a 10-day affair held each July, celebrated its centenary in 2012. That year saw more than 1.4 million visitors. Even Weadick would’ve hesitated to dream that big. Maybe.

He certainly didn’t hesitate to leave his hometown. Some might say Guy Weadick reinvented himself while out West. Or maybe he went westward to be who he really was.

_______________

THE CALGARY STAMPEDE TODAY

By Mark Kolakowski

During its 10-day run, the 2019 Stampede had 1,275,465 visitors, second only to the more than 1.4 million who attended the Centennial Stampede in 2012. The next Stampede runs from July 3 through July 12, 2020, and tips for first-time visitors include:

• Plan to attend at least three days, maybe four.

• Book a hotel that is walking distance to Stampede Park and the downtown events on Stephen Avenue and Olympic Plaza that take place every day except Sunday. The latter include: free chuckwagon pancake breakfasts, free concerts, square dancing, First Nation (Native American) horseback parades, and vintage carriage parades.

• Book tickets in advance for the afternoon rodeo and the evening show, but not on the same day. These tickets include general admission to Stampede Park at no extra cost.

• Best rodeo seats: first few rows of the infield, preferably near the south end.

• Best evening show seats: near the finish line about midway up the grandstand.

• Since 14 or more events may go on simultaneously in Stampede Park, plan your daily itinerary in advance. There can be last-minute changes, so check the Stampede website even after your arrival. (calgarystampede.com).

• Some top things to see: Team Cattle Penning, the World Stock Dog Championship (sheepherding), the World Six Heavy Horse Show (teams of six draft horses pulling vintage wagons, with live music from the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra), the Calgary Stampede Showband (six-time world marching band champs, most recently in 2019), the Calgary Stampede Showriders precision riding team, Draft Horse Town, and the Elbow River Camp (formerly the Indian Village).

• Each year, there are 50 or more new, one-time-only foods on the midway that range from inventive to outrageous. Check the website to plan your meals and snacks.

• If you love a parade, be there on Friday, July 3, for one of the biggest in North America, which kicks off the event.

• You can buy multi-day discounted tickets to Stampede Park in advance. However, these may not make sense if you buy rodeo or grandstand show tickets in advance (see #3 above), or enter during a period when they offer free or discounted admission to walk-up customers.

Leave a Reply