What did the famed poets and writers get up to when they crossed the Atlantic?

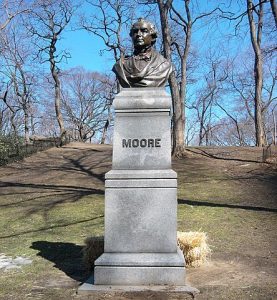

Dublin-born THOMAS MOORE (1779-1852) is still recognized as Ireland’s National Bard; he was once as famous a romantic poet as his best friend Lord Byron.

While studying law in London in 1801 he published, anonymously, a book of naughty verses, The Poetical Works of the Late Thomas Little. The author was “the most licentious of modern versifiers,” thundered The Edinburgh Review. Nevertheless, in 1803 young Moore was appointed registrar to the British Admiralty in Bermuda.

After three tedious months on the island, the sensation-seeking poet sailed away to nearby Virginia, leaving a deputy in his place. From Norfolk, he traveled to Washington, where he stayed with the British ambassador and, in the half-built White House, briefly met President Thomas Jefferson. POTUS reportedly ignored the diminutive Irish poet, mistaking him for a child. Miffed, Moore composed a poem on the taboo subject of Jefferson’s black mistress, Sally Hemmings:

“The weary statesman for repose hath fled

From halls of council to his Negro’s shed,

Where blest he woos some black Aspasia’s grace,

And dreams of freedom in his slave’s embrace!”

The bard then traveled northwards through various American towns and cities, stopping at Niagara Falls, and then sailed back to Britain from Nova Scotia.

In 1907, Moore issued the first volume of his Irish Melodies, collections of such songs as “The Last Rose of Summer,” “Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms,” and “The Minstrel Boy.” The lyrics enjoyed instant, extraordinary popularity; Americans alone bought a million and a half copies of the sheet music for “The Last Rose Of Summer.”

In 1817, Longmans agreed to advance him £3,000, the highest price ever paid for a poem, for his metrical romance, Lalla Rookh. In 1819 he learned that his deputy in Bermuda had absconded, leaving a debt of £6,000 for which Moore was responsible in law. Easy come, easy go.

Moore eventually issued a public apology for his “rash” insults to the American president; for his part, Jefferson had taken a great liking to the poems of “the little man who satirized me so.”

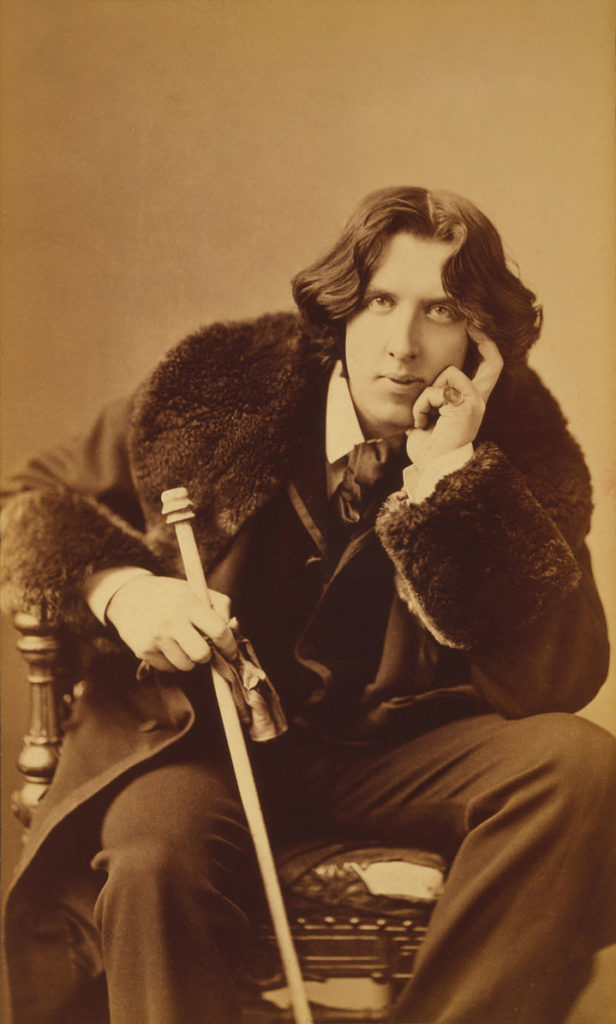

On a January day in 1882, the young Irish poet and wit OSCAR (Fingal O’Flahertie Wills) WILDE (1854-1900), wearing a long fur-trimmed green coat, knee breeches, silk stockings, and silver-buckled pumps, arrived in New York to undertake a lecture tour of 15,000 miles over 140 cities and towns.

Gilbert and Sullivan had composed an operetta, Patience, that was a satire of the English “aesthetic” movement in general and Oscar (as “Reginald Bunthorne”) in particular. Richard D’Oyly Carte, the impressario, hired Wilde to give a lecture tour across the United States in order to demonstrate what Patience was mocking.

The longhaired poet’s itinerary took him as far west as San Francisco and as far south as New Orleans. He was unimpressed by Niagara Falls (“Every American bride is taken there, and the sight of the stupendous waterfall must be one of the earliest, if not the keenest, disappointment in American married life.”) He bonded with Walt Whitman in New Jersey and offended Henry James in Washington, D.C. In Atlanta he was informed that under no circumstances could his black valet travel in the same railway car with him.

He drank a gang of silver miners under the table in Leadville, Colorado, where on the wall of the Silver Dollar saloon he discovered “the only rational method of art criticism I have come across. Over the piano was a printed notice: ‘Please do not shoot the pianist, he is doing his best.’”

Back in NYC at the end of his tour – he had grossed $40,000 – Oscar encountered a charming young man who claimed to be the son of a Wall Street banker. In his company, Wilde lost over $1,000 playing with (loaded) dice. From a series of mug shots at the police station, he identified the swindler: it was notorious con man and bunko artist “Hungry Joe” Lewis.

Oscar sailed back to England and cut his hair. He made just one more trip across the Atlantic, in August 1883, for the New York opening of his play Vera, or The Nihilists. Despite a huge marketing campaign (the costumes were on display in the windows of Lord and Taylor’s on Fifth Avenue), Vera was panned by the critics and closed in a week.

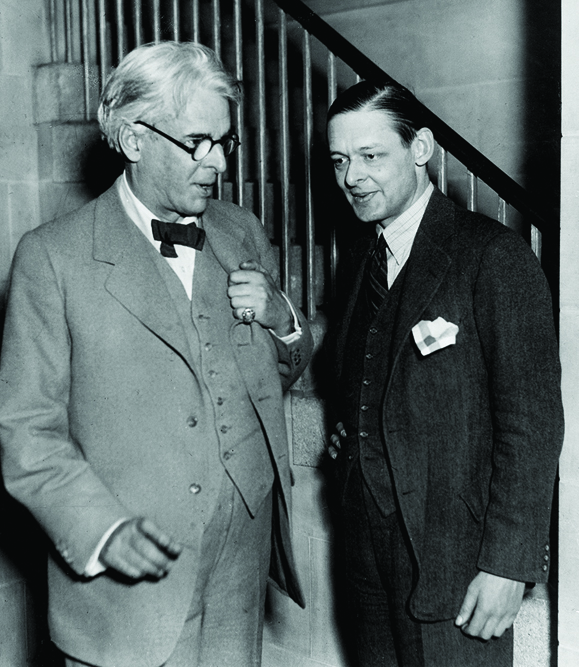

W. B. YEATS (1865-1939) spent more than a year of his life in the United States, during five visits between 1903 and 1932.

The first visit he undertook shortly after learning that his beloved Maud Gonne had married a drunken, vainglorious lout. He was contracted to deliver more than 60 lectures at leading learned societies and universities across America. The fee was $75 for each.

Soon after his arrival, he lunched with President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House. When the president spoke of the needs of the “little people,” the poet assumed the statesman was referring to the Little People, whom he himself had often encountered. “Sure, not only I, but every Irishman, especially the old ones that mow the hay in the twilight, have seen the Little

People many and many a time; but they are not small insignificant creatures, like the English fairies; they are giants, the old gods come back again.”

His schedule was grueling but he found his 10-day sojourn in San Francisco thoroughly gratifying. Back in New York he lectured on “The Intellectual Revival in Ireland” at Carnegie Hall on January 3, 1904, before a large and enthusiastic Irish-American crowd, then departed for England with a profit of $3,200, a substantial sum at that time.

In 1911 Yeats returned, accompanying the Abbey Players on their first American tour, bringing 17 new plays to American audiences, including J.M. Synge’s controversial The Playboy of the Western World. “In New York, a current cake and a watch were flung, the owner of the watch claiming it at the stage door afterwards.” (WBY, The Irish Dramatic Movement). Other outraged audiences threw potatoes and rosaries. The entire cast of Playboy was arrested in Philadelphia for performing an “immoral or indecent” play. But the tour was counted a success.

In 1914 the impecunious arch-poet was back, this time raising £500.

In 1920 Yeats, accompanied by his new wife, George Hyde-Lees, embarked on a tour of the U.S. and Canada to raise funds for the re-construction of Thoor Ballylee, their stone tower in Galway – according to Ezra Pound, “to make enough to buy a few shingle for his phallic symbol on the Bogs.” In their spare hours on the road, the couple engaged in automatic writing sessions, with Mrs. Yeats contacting a spirit guide scalled “Leo Africanus.”

The Nobel laureate’s final American tour (1932-33) was intended to boost his own finances and to raise money for his latest project, the Irish Academy of Letters. This was Yeats’s (unsuccessful) effort to oppose the church- and state-sponsored literary censorship that had been introduced during the 1920s.

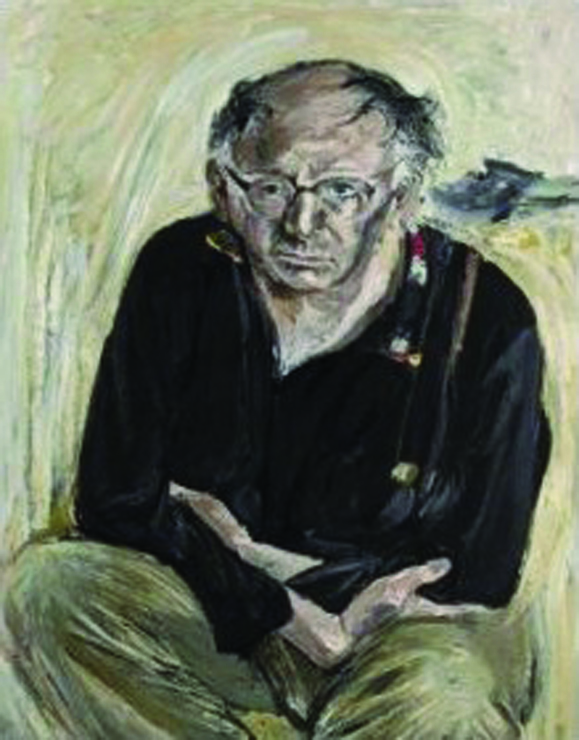

PATRICK KAVANAGH landed in New York in 1956, at the invitation (and expense) of John and Dede Farrelly, American friends who were concluding a year’s stay in Dublin. He enjoyed himself greatly and enjoyed the company of Beat poets Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso in the Farrellys’ New York apartment.

Almost 10 years passed before Kavanagh was invited to Northwestern University to participate in a symposium on the work of W. B. Yeats. Kavanagh was delighted to take advantage of a generously funded visit to Chicago, despite his scorn for all things Yeatsian. But Chicago itself

proved a disappointment; the potato farmer from Co. Monahan found the City of the Big Shoulders “provincial.” For his part in the symposium he played the contrary curmudgeon, denying that there was any such thing as a literary tradition, Irish or otherwise. “Yeats wasn’t Irish and never wrote a line that any ordinary Irish person would read,” he declared. “The only men in America that are alive are men like Jack Kerouac.”

After sneering at “all this pretention and bawling lecturology that’s Americanism,” he traded insults with audience members until Stephen Spender, who was moderating the discussion, put an end to it – and to Kavanagh’s possible future in the Groves of American Academe.

Between 1960 and 1964, BRENDAN BEHAN made four extended visits to the America, usually making New York’s Chelsea Hotel his base of operations. (Bernard Geis, Behan’s American publisher, erected a plaque outside the Chelsea that memorializes Brendan’s time there). To Behan, New York was the “greatest show on earth, for everyone” and “my Lourdes, where I go for spiritual refreshment.” It was also, as he observed, “the place where you are least likely to get a bite from a wild sheep.”

When his play The Hostage became a hit on Broadway in September 1960, the sudden wave of celebrity knocked him off the wagon.

In the U.S. from year to year, Brendan went from being a charming “drinker with a writing problem” to an obnoxious caricature of the mean drunken Irishman. He became the first person in history to be banned from the New York City St. Patrick’s Day Parade. He cheated on his wife Beatrice with men and women; in San Francisco he fathered a child with Ernest Hemingway’s secretary. He escaped naked from a New York hospital. When Beatrice visited him in May 1963 to tell him she was pregnant, she found him in a stupor, mumbling of his lust for Spanish boy dancers.

She took him home to Ireland, where he died from sclerosis of the liver and his neglect of his diabetes. Behan’s plaque on the front of the Chelsea Hotel features a quote. “To America, my new found land: The man that hates you hates the human race.” He loved America. In return, America

loved him. To death. ♦

Leave a Reply