“How hard Ireland was on the women who could not fit in – the wild ones, the ones who had to get out, seeming emigrants but actual exiles.”– Nuala O’Faolain

Chicago May wasn’t from Chicago and, in fact, spent little time there, but the name somehow suited her. May Duignan was born in 1871 in the remote county of Longford in the ancient world that was 19th-century Ireland. Her young life was a slog of backbreaking work on the farm and by age 19, she knew she had to get out. But how? Her parents weren’t coming through with money for emigration. She could marry a local bachelor-man, but that life invariably came with a cranky crone (his mother), and more farm work. Of course there was always the convent, but somehow May didn’t hear the call of a vocation.

In 1892, after helping her mother give birth to her latest child, May slipped out the door, family savings under her cloak and dreams of adventure in her head. She tripped lightly across four continents, a buxom and fun-loving scoundrel with red-gold hair, the heartiest of laughs and a simmering sexuality.

Immigrants always undergo some kind of re-invention, but May’s was, to say the least, extreme. In 1907, 15 years after she fled Ireland, she was in The New York Times, described as, “the blue-eyed siren who has lured so many men to their doom.” May, who came from a priest-ridden world where skipping Sunday Mass was a mortal sin, managed to effortlessly transition to the decadence of the New World – the farmgirl had become a “blue-eyed siren.” She was a woman of pure id, never evidencing any guilt, shame, or remorse – emotions that should have been embedded in her DNA. They weren’t.

Nicking the family nest egg may have been her first crime, but it wasn’t her last. She was a blackmailer – the first to use a hidden camera – a forger, a thief, a burglar, a prostitute – or, as she preferred, a “badger” (a two-dame operation: one has sex, the other robs the john) – and an accomplice to a bank robbery. May perfected the fine art of the fainting fit, a feigned state that allowed her to steal watches and wallets and suck diamonds from tie-pins of the gents who came to her aid.

May planned, if at all, badly. She lived on the edge and in the moment, without a thought to her future. Always on the move, she never had a permanent home. She made lots of money but held on to none of it, oblivious to her financial security. Generous, May was an easy touch, paying her pals’ rent or bail, and with the roll of bills in her garter, she was always ready to stand a crowded bar to rounds of drink.

Back to where it all began, that night in 1892: May made tracks out of Longford, holding her stash close until she reached Liverpool, where she bought some glamorous duds and a first-class ticket to America. In her excellent biography of May, Nuala O’Faolain describes her flight: “Off she sailed with her red-gold hair and blue eyes and raucous voice and tough-as-nails mannerisms and reckless energy.” After arriving in New York, May took off for Nebraska looking for an uncle, but instead found a full-fledged outlaw, Dal Churchill, a member of the notorious Dalton Gang. Dal, like most men, was instantly smitten with May and they wed. But soon after the nuptials, the bridegroom was caught robbing a train and summarily lynched by an angry mob. The young widow had American citizenship, a new name, Churchill, and she bolted the Badlands pronto, heading north.

She found herself in Chicago, another penniless Irish immigrant and worse, a woman alone with few job opportunities – saving domestic work. May then did what the catechism warned against, she “fell in with bad company,” and landed between the cracks of morality and the law. She joined the tribe of loose women, flimflam artists, and thieves; in her 1928 autobiography, Chicago May, Her Story by “The Queen of Crooks,” May defends her decision, “Did I not know that the rewards of steady industry were pitiful compared with the easy, if uncertain, windfalls of crime?” She set up shop in the red-light district, worked the World’s Fair of 1893. Chicago May was born.

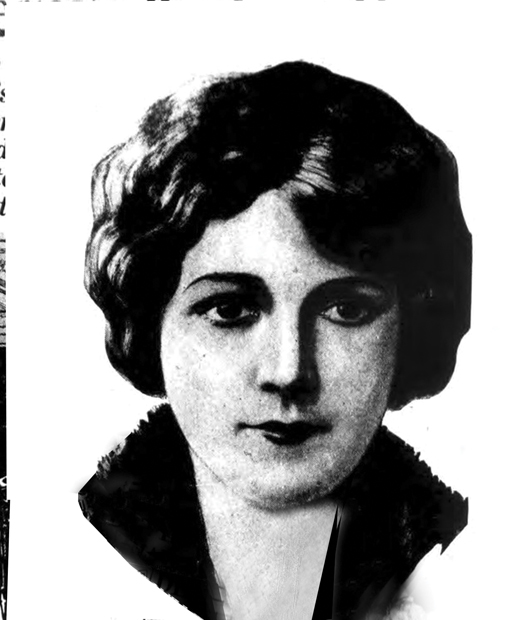

The fair left town, taking May’s business with it, but ever resourceful, she found work in a gambling club in Egypt, and soon “Cairo May” was sailing down the Nile. Her Cairo expedition was short-lived because she wanted to conquer New York. May traveled across countries, oceans, and rivers to arrive in the city’s notorious Tenderloin district, a writhing pit of gangsters, grifters, and whores. She was right at home. May’s curvaceous body and kewpie doll face belied her physical strength and violent nature – she was a powerful woman known for her roundhouse punches and capacity for alcohol. Some nights she swanned around as “Diamond May,” the grande dame in pearls and furs, on others she was the fierce fighter in the center of a brawl.

She met James Sharpe, a sot and son of a wealthy family who fell in love with her. They wed, and on her wedding license she put May Lettimer as her name and 21 as her age (she was actually 27). Mother Sharpe suspected something fishy about her new daughter-in-law, but believed she was tough enough to get Jim on the natch. May, in turn, believed the family would lavish their fortune on the newlyweds but discovered that James, the family black sheep, was only allotted a weekly allowance befitting an 11-year old. She also learned he was batty, constantly planning to murder his family. After a year in New Jersey avoiding her husband and drinking tea with her mother-in-law, she went back to the city. James enlisted in the Spanish-American War and was never heard from again.

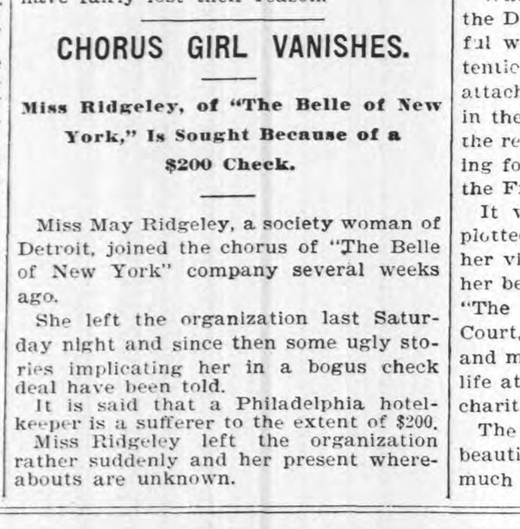

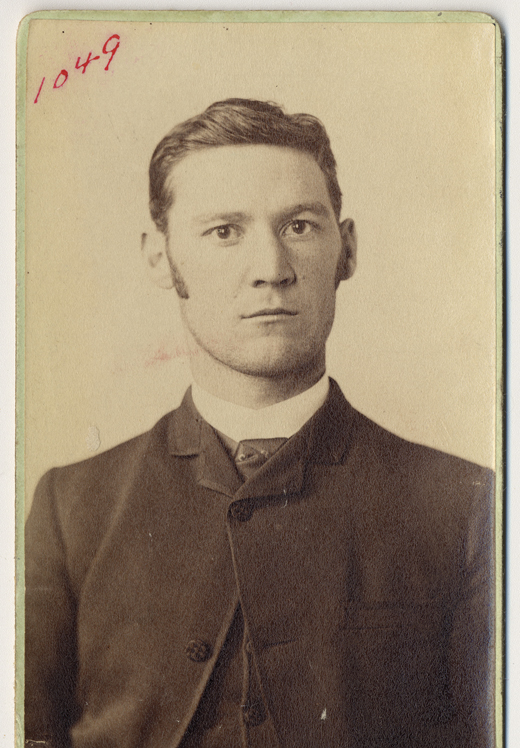

She now had a new name – courtesy of both hubbies and adding the fanciful “Vivienne,” she was May Vivienne Churchill Sharpe – and a new look, Gibson Girl. At 28, her hardscrabble life and alcohol consumption hadn’t diminished her appeal, and she landed in a hit musical, The Belle of New York. She traveled with the show throughout the United States and then on to London, where May, both beautiful and beautifully dressed, left her shady-lady past on the other side of the Atlantic. This could have been the high point of her life, except Eddie Guerin, the man she would later describe as “the source of all my trouble,” happened to be in London at the same time. Eddie was an Irish-American gangster who became so enthralled with May (“Her beauty held me spellbound”) that he completely forgot he had gotten married just two weeks earlier. May was likewise besotted, and immodestly wrote, “Both us were successful, prosperous thieves…good-looking, healthy, vigorous, well-dressed specimens of our respective sexes.”

They traveled to Paris where they strolled the city looking like just another pair of romantic tourists, except Eddie was planning a bank robbery and enlisting May as the lookout. This was to be her official entry into major crime. The gendarmes caught Eddie and his gang, but May escaped to London. Whether it was love or loyalty or her reckless nature, she returned to Paris thinking she could help Eddie, but instead went to trial with the gang. She was sentenced to five years in a woman’s prison, but Eddie got 20 years in Devil’s Island, notorious for its systemic torture, vampire bats, and the sharks that kept circling the island, making it impossible for prisoners to escape. In its infamous history only a handful of prisoners escaped and Eddie Guerin, a two-bit con from Chicago, was one of them. He ran, sailed, and swam his way out of Devil’s Island, endured starvation, malaria and “savages,” all the while fulminating about his fate – he put the blame on May. News of his escape made headlines everywhere: England hailed him as a daring desperado, France claimed him as a fugitive prisoner needing to finish his sentence, and May knew he was a madman vowing to kill her.

May, too, escaped prison using her usual M.O.: she seduced the prison’s doctor, then threatened him with blackmail and got an early release. Hearing Eddie was on the loose from Devil’s Island, May scurried to South America and plied her trade at the Pan American trade conference in Rio, a venue filled with lonely businessmen. There, a diplomat with ties to British royalty, Sir Sidney Hamilton Gore, became taken with May and she, always a throne-sniffer, was ecstatic. Gore escorted the famous whore (and now, jailbird) to the “ball of the decade,” where a fabulously dressed May, on the arm of her aristocrat admirer, danced all night. After the ball they strolled in the moonlight (or got drunk, accounts vary) and he proposed marriage. But there was no happily ever after because Gore, soon after they parted, shot himself in the head. Yet another scandal in the adventures of Chicago May.

Meanwhile, Eddie, having been arrested on his return to London, was in prison awaiting extradition to France. There he struck up a friendship with another prisoner, Charley Smith, and beefed how May had done him wrong. On the eve of Charley’s release, Eddie ordered him to kill her or at the very least, lop off an ear. Charley set out to follow Eddie’s orders until…he met May. It was love at first sight, but their idyll was cut short when the couple got some bad news – Eddie was free and on the streets of London. Charley thought they should run away but May (“I’m not yellow”) refused, so Charlie decided to kill Eddie; it was the only way to keep May safe. The threesome had a standoff in Russell Square, Charley shot Eddie in the foot, and after a sensational trial, Charley and May, in 1907, were convicted of attempted murder.

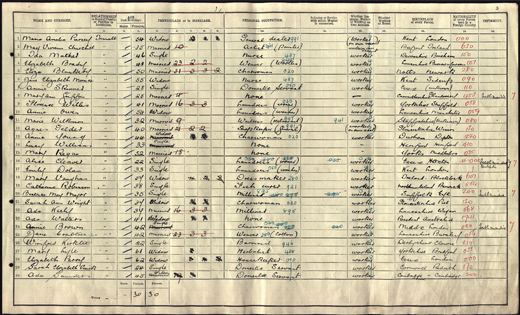

May was sentenced to 15 years in Aylesbury Prison for Women, always a difficult stretch for Irish prisoners as they faced continual prejudice from the British guards. The 1911 Census was taken in Aylesbury and there one May Vivienne Churchill put down a string of lies, claiming to be an artist/painter, aged 35, married and – in a ploy to pass as an artiste descended from Ascendancy Protestants – gave her birthplace as Belfast. This changed after May became friends with another prisoner, Countess Constance Markiewicz, the “grandest woman I ever saw.” The countess inspired some nascent nationalism in May and, during their time together in Aylesbury, enlisted her in Rebel protests. May served 10 years of her sentence and once out, Great Britain deported her to America, grateful to be rid of this troublesome redhead. Charley served the full 20 years. And Eddie? He had lost two toes but continued a life of crime, albeit petty, pinching pocketbooks and nylon stockings.

Back in New York, May tried to go straight but as she poignantly states in her autobiography, “I became bad again.” She was 46 and the face, body and sassy style – those moneymakers that turned her into an Irish Circe – were gone. She was now, officially, “more sinned against than sinning.” She had a new man – a violent pimp who forced her to walk the streets on varicose-veined gams – he took the money while May landed in the clink. She found herself in solitary confinement in a Detroit prison, lying on a stone floor trying to pass a kidney stone, a moment described by O’Faolain, “It is hard to imagine anyone with more of a past and less of a future.”

The creepy satanist, Aleister Crowley, wrote a nasty poem about one of his ex-girlfriends, but refrained from identifying her and instead used a name that had become synonymous with sordid. His opus “Chicago May: A Love Poem” begins, The great sow snores / Blowing out spittle through her blubber lips / Champagne and lust still oozing from her pores. It only gets worse from there.

A social reformer and criminologist, August Vollmer, now entered May’s life, visiting her in the hospital while she recovered from kidney surgery. Vollmer, “a good-hearted bull,” knew her story and suggested a good way to go straight: write her autobiography. She did, and produced a brave, if dissembling, account of her life, published in 1928. Then, in 1929, Charley Smith, the man who spent 20 years in prison for May, traveled to America to see his lost love. As soon as he arrived Charley went to see May, again in the hospital, and they spent every night and day holding hands. He proposed, she accepted and they picked an upcoming date for their wedding: May 30, 1929. That turned out to be the day Chicago May, in Philadelphia, died on the operating table. She was 58. The sole mourner at her funeral was a stranger, a nun.

In 1927, Genevieve Forbes Herrick wrote a story in The Chicago Tribune presenting May as a feminist, and “a pioneer of women’s rights in the male-dominated world of crooks.” May didn’t think of herself as a feminist (it’s doubtful she knew the meaning of the word), but she knew she had enough moxie to do what few women of her time could do: get off the farm and head out into the unknown. Like all immigrants, she re-invented herself, though she did so more flamboyantly and more dangerously than most. O’Faolain writes, “May’s story is not a negative story at all – life dealt her this hand of cards, and she played it her way. In her terms, her life was a success – her great adventure.” ♦

_______________

Rosemary Rogers co-authored, with Sean Kelly, the best-selling humor / reference book Saints Preserve Us! Everything You Need to Know About Every Saint You’ll Ever Need (Random House, 1993), currently in its 18th international printing. The duo collaborated on four other books for Random House and calendars for Barnes & Noble. Rogers co-wrote two info / entertainment books for St. Martin’s Press. She is currently co-writing a book on empires for City Light Publishing.

Leave a Reply